The draft security agreement between China and Solomon Islands circulating on social media raises important questions about how the Australian government and national security community understand power dynamics in the Pacific Islands.

In Australian debates, the term “influence” is often used to characterise the assumed consequences of China’s increasingly visible presence in the Pacific.

There’s an assumption China generates influence primarily from its economic statecraft. This includes its concessional loans, aid and investment by state-owned enterprises (which partly manifests in Beijing’s involvement of Pacific Islands in its Belt and Road Initiative).

On its face, the leaked draft seemingly proves Chinese spending “bought” enough influence to get the Solomon Islands government to consider this agreement. But such an interpretation misses two key issues.

The role of domestic politics

First, the draft agreement is primarily about Solomon Islands domestic politics – not just geopolitics.

As explained by Dr Tarcisius Kabutaulaka after the November 2021 riots in Honiara, geopolitical considerations intersect with, and can be used to, advance longstanding domestic issues.

These include uneven and unequal development, frustrated decentralisation, and unresolved grievances arising from prior conflicts.

Power in the Pacific is complex. It is not just politicians in the national government who matter in domestic and foreign policy-making.

Take, for example, the activism of Malaita provincial governor Derek Suidani, who pursued relations with Taiwan after Solomon Islands switched diplomatic recognition to China in 2019. This highlights the important role sub-national actors can play in the both domestic and foreign policy arenas.

Neither Solomon Islanders (nor other Pacific peoples) are “passive dupes” to Chinese influence or unaware of geopolitical challenges – and opportunities. Some do, however, face resource and constitutional constraints when resisting influence attempts.

Australia’s current policy settings are not working

The second key issue is that Australia’s current policy settings are not working – if their success is measured by advancing Australia’s strategic interests.

Australia is by far the Pacific’s largest aid donor and has been on a spending spree under its “Pacific Step-up” initiative.

Australia spent billions leading the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI), as well as significant bilateral programs to the country. Yet Australia has not been able to head off Honiara considering the security agreement with China.

Read more: As Australia deploys troops and police, what now for Solomon Islands?

Perhaps Canberra has not sought to influence Solomon Islands on this matter. But given Australia’s longstanding anxieties about potentially hostile powers establishing a presence in the region, this is unlikely.

Home Affairs Minister Karen Andrews has already commented in response to the leaked draft that:

This is our neighbourhood and we are very concerned of any activity that is taking place in the Pacific Islands.

The rumours (subsequently denied) that China was in talks to establish a military base in Vanuatu, and China’s attempt to lease Tulagi Island in Solomon Islands had already intensified Australia’s anxieties. Such concerns partly motivated the government’s investment in the Pacific Step-up.

A closer look at the draft security agreement

The terms of the draft security agreement should make Australia anxious. It goes significantly beyond the bilateral security treaty between Solomon Islands and Australia.

Article 1 provides that Solomon Islands may request China to “send police, police, military personnel and other law enforcement and armed forces to Solomon Islands” in circumstances ranging from maintaining social order to unspecified “other tasks agreed upon by the Parties”.

Even more concerningly for Solomon Islands’ sovereignty, Article 1 also provides that

relevant forces of China can be used to protect the safety of Chinese personnel and major projects in Solomon Islands.

It remains unclear what authority the Solomon Islands government would maintain once it consents to Beijing’s deployment of “relevant forces” to protect Chinese nationals.

Article 4 is equally vague. It states specific details regarding Chinese missions, including “jurisdiction, privilege and immunity […] shall be negotiated separately”.

The agreement also raises questions about the transparency of agreements Beijing makes and their consequences for democracy in its partner states.

According to Article 5,

without the written consent of the other party, neither party shall disclose the cooperation information to a third party.

This implies the Solomon Islands government is legally bound not to inform its own people and their democratically elected representatives about activities under the agreement without the Chinese approval.

The version circulating on social media may prove to be an early draft. Its leak is likely a bargaining tactic aimed at pursuing multiple agendas with multiple actors – including Australia.

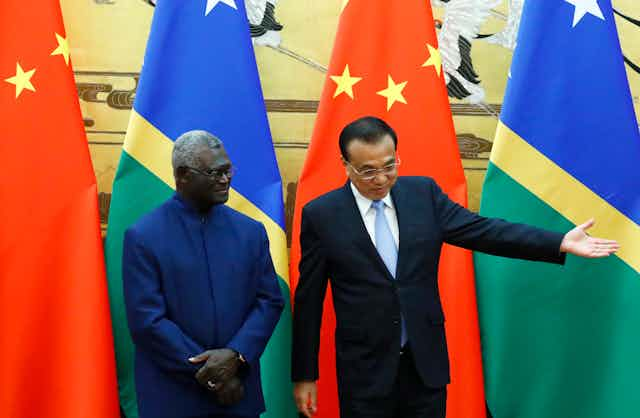

Australian High Commissioner Lachlan Strahan met yesterday with Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare and announced Australia will extend its assistance force until December 2023. It will build a national radio network, construct a second patrol boat outpost, and provide SI$130 million (A$21.5 million) in budget support.

Playing whack-a-mole

While the timing was likely coincidental, it highlights an emerging dynamic in Australia’s Pacific policy: playing whack-a-mole by seeking to directly counter Chinese moves through economic statecraft. Think of Telstra’s recent purchase of Digicel Pacific, headquartered in PNG – a move seen by some analysts as really an attempt to shut China out of the Pacific.

That China has been able to persuade Solomon Islands to consider an intrusive security agreement raises questions about our understanding of how power and influence are exercised in the Pacific.

If influence is taken to result in concrete behavioural changes (such as entering into a bilateral security agreement), and if Australia is going to “compete” with China on spending, you’d need to ask, for example: how much “influence” does an infrastructure project buy?

This understanding of power, however, is insufficient. Instead, a more nuanced approach is required.

Influence is exercised not only by national governments, but also by a variety of non-state actors, including sub-national and community groups.

And targets of influence-seekers can exercise their agency. See, for example, how various actors in Solomon Islands are leveraging Australia, China and Taiwan’s overtures to the country.

We must also consider how power affects the political norms and values guiding governing elites and non-state actors, potentially reshaping their identities and interests.

The draft security agreement may come to nothing – but it should provide a wake-up call to Australia and its partners.

Old assumptions about how power and influence are exercised in the Pacific need urgent re-examination – as does our assumption that explicitly “competing” with China advances either our interests or those of the Pacific.