There’s been a lot of trouble in the nation’s capital lately.

The United States just endured a monthlong government shutdown affecting services ranging from airline travel to tax collection.

Congress and the president have battled over where and even whether to hold the State of the Union.

Plus, late last year, a federal judge blocked the Trump administration from enforcing new immigration policies that would limit migrants to seeking asylum at established border checkpoints. When President Trump dismissed this ruling as the product of a politically motivated “Obama judge,” Chief Justice John Roberts pushed back, invoking the spirit of the Thanksgiving holiday in stating that an “independent judiciary is something we should all be thankful for.”

And if we push beyond these headline stories, we can see that government’s bread and butter operations, like appointing judges or passing meaningful legislation, have slowed and become subjects of pitched political fights.

Of course, clashes between the branches of government are nothing new. Indeed, they are actually baked into our constitutional design.

The founders built a system of government with three separate branches – we call it the “separation of powers” – that are each supposed to monitor and check the actions of the others in order to prevent abuses of power.

But given the breakdowns in functioning within all three branches, it might appear that the separation of powers system is broken or unbalanced. Or perhaps the human element essential for the separation of powers to function properly has stopped working?

No clear concept

According to America’s first president, George Washington, the experiences of the early United States, not to mention “ancient and modern” nations across the globe, demonstrated the “necessity of reciprocal checks in the exercise of political power” to protect the public interest.

While the U.S. Constitution gives specific and implied powers to the national legislative, executive and judicial branches, there’s no separation of powers clause or specific reference, as there are in other national constitutions like those found in Croatia, the Dominican Republic and Turkey.

The framers of the U.S. Constitution had varying ideas about what our separated powers are designed for. I’ve conducted research on the separation of powers showing that there’s also no clear consensus among contemporary judges or scholars, either.

Still, there are a few broadly accepted features of our separated powers system.

Most people see separation of powers as the federal government’s division into three branches, legislative, executive and judicial, each with a special job.

Scholars and other constitutional experts note that this division of powers is mixed and somewhat messy.

For example, Congress has the lion’s share of legislative power. But the president can both veto bills and recommend to Congress “such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient,” according to the Constitution.

This untidy power-sharing is supposed to avoid what founding father James Madison called “the very definition of tyranny” – all power in one set of hands. That means we give ambitious politicians tools that bring them into conflict as a way of limiting the power of any one person or branch.

The Constitution and its separation of powers is not a clean division of labor, but what scholar Edward S. Corwin dubbed an “invitation to struggle,” where elected officials protect their branches – and themselves – by meddling, being alert and, where necessary, confrontational.

In other words, what’s supposed turn the Constitution into what poet James Russell Lowell called “a machine that would go of itself,” is a set of rules and organizations fueled by certain kinds of behavior among those in power to make that system work.

The separation of powers is more like a guidebook for running an effective poker tournament rather than a set of instructions for a specific piece of Ikea furniture.

An incomplete sketch

But this view of the separation of powers, focused on negative checks, a federal division of powers and leaders jealous and protective of their institutional powers, is only half of the story.

Our constitutional powers “were divided to make possible their effective use … to prevent deadlock, not to create it,” wrote Ann Stuart Anderson, a researcher at the American Enterprise Institute.

So the separation of powers is more than checks and balances designed to prevent mischief.

“Workable” government requires human qualities that go beyond the architecture of government. We need some level of cooperation, deference and mutual respect from the people within government.

This is what Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt have called the norms of “mutual toleration” and “forbearance.”

As former Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy put it during his appearance at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on strengthening judicial independence in 2007, the “separation of powers and checks and balances are not automatic mechanisms. They depend upon a commitment to civility, open communication, and good faith on all sides.”

So, for example, the president is constitutionally permitted to exercise the veto. But presidents must use that power judiciously. It would presumably violate the spirit of the separation of powers if the chief executive vetoed legislation every time he didn’t get his way.

The public expects more

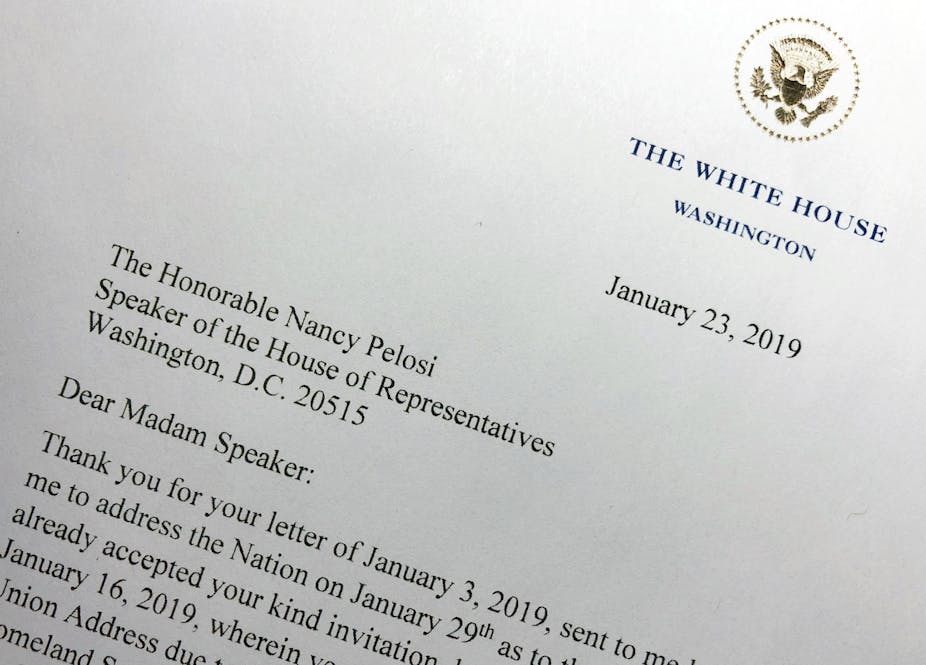

For those who watched the fight between House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and President Trump over when he could deliver the State of the Union address, it might appear that the civility and mutual respect required to keep our separated powers working smoothly are no longer present.

And the incident, along with the shutdown, prompts the question: Is our constitutional separation of powers broken or working?

The glib, but probably accurate answer is: both.

Like his predecessors, President Trump continued to sign bills into law while the government was shut down. Because of the Antideficiency Act, “essential” government departments, like the U.S. military and courts, continued to operate even after their traditional funding sources expired.

And some states, like California and Colorado, responded to the federal stalemate by extending unemployment benefits to government employees working without pay.

But this patchwork of policies and short-term fixes may not be enough when it comes to the inevitable next shutdown, or for tackling even bigger issues facing the nation, including immigration, climate change or the ongoing threats of terrorism and cyberwarfare.

And the well-documented cratering of public trust in government – with only 18 percent of Americans in 2007 saying they regularly trust the “government in Washington” to do what is right, compared with 77 percent in 1964 – shows that “We the People” expect something more.