A few years ago I conducted a feminist analysis of the Liberal Democrats as my PhD thesis. During the research, people (both inside and outside of the party) would often say my project was “a bit niche”, and I tended to agree. Now, however, the Liberal Democrats’ approach to women has become headline news, with regards to the quality of their procedure for handling complaints, particularly in relation to the allegations of sexual harassment against Lord Rennard raised with senior members of the party as early as 2007. and continued press coverage of the party’s failure to secure the election of more women MPs (women currently constitute just seven of the 57 Lib Dem MPs).

My initial motivation for studying the Lib Dems was to understand how a party that claimed to promote equality and fairness could have such a poor record with regard to women’s representation. I interviewed and surveyed around 200 women involved with the party – MPs, peers, election candidates, local councillors and party workers. There was plenty of disagreement on the much-debated use of gender-based quotas to increase the number of women MPs, but nearly all of my female interviewees said it was harder for women in the party to get selected and elected.

They observed that women faced significant barriers such as time, money and issues of self-confidence; many reported instances of indirect discrimination on the part of selection panels, where automatic assumptions were made about their capabilities because of their gender. Underpinning these obstacles (which of course affect women from across the parties to varying degrees) was also a sense that the party didn’t really take gender seriously. This has been underscored over the past year, as the party has sought to respond to the allegations made against Lord Rennard. The police decided that no criminal charges should be brought against Lord Rennard.

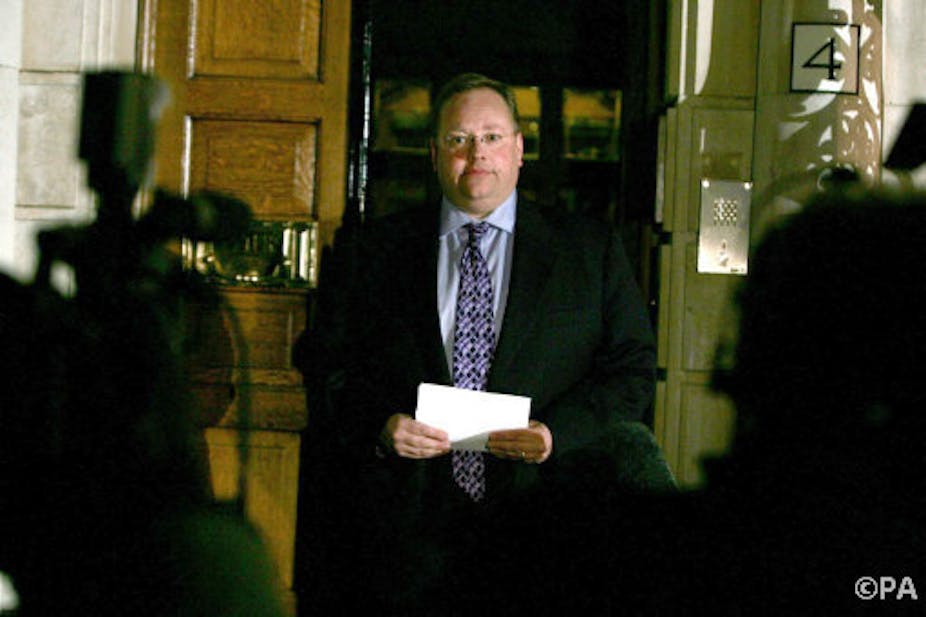

The Lib Dem finally conducted an internal investigation in 2013. This investigation found that the evidence suggested that Lord Rennard’s behaviour had caused distress to a number of women, so much so that they came forward several years after the events in question. It nevertheless concluded that it was unlikely that it could be established beyond reasonable doubt that he intended to act in an indecent or sexually inappropriate way.

The women who made the allegations are furious at the party’s response to the issue. The Lib Dems’ labyrinthine committee structure, which guarantees a strong voice for activists, has meant that the leadership has not been able to act decisively when it has really mattered.

Rennard is threatening to sue the party for pursuing a second disciplinary inquiry and for suspending him from the party. The leadership is seeking an apology from him after their own inquiry decided “no further action” should be taken but that “Lord Rennard ought to reflect upon the effect that his behaviour has had and the distress which it caused and that an apology would be appropriate, as would a commitment to change his behaviour in future”. Put simply, the lack of an internal process for dealing quickly with the allegations has exposed the party’s failure to fully transition from a volunteer-led party of permanent opposition to a professional party.

As the UK’s third party, the Lib Dems have often had to operate on a shoestring budget. Those who work or volunteer for the party know all too well the sheer number of hours required to distribute the latest Focus leaflet, to organise fundraising events, and to canvass local opinion on a Saturday stall in the high street. Many of the women I interviewed observed that the amount of time activists and party workers had to dedicate to the party effectively excluded women, in particular those with caring responsibilities.

More seriously, however, my work suggested that allegations of sexual harassment and discrimination highlighted in my work were not isolated incidents within the party. Many women I interviewed told me about inappropriate behaviour, leading and sexist questions during candidate selection processes, sexist and racist jokes made in their presence, and female interns being expected to “put up with” unwanted attention from MPs. While some women made formal complaints, others did not.

Perhaps one of the most worrying aspects has been the party’s failure to take those complaints that were made seriously. Given that the party places such great store in the role of activists, it is encouraging to hear that the grassroots are lobbying the leadership to force Rennard to apologise as recommended in by their own investigation. Unfortunately, the fact that Rennard is the subject of the allegations is not in itself insignificant; given Rennard’s powerful support base and forensic knowledge of the party’s procedures and by-laws, it is hard to imagine Clegg being able to expel him from the party.

The party leadership must look to change internal procedure in order to set up a proper complaints process. The Morrissey report recommended appointing a pastoral care officer and providing further diversity training, but issues of sexism and sexual harassment require a wider cultural shift: one that ensures gender is taken seriously.