We seem to be living in a new era of forensic investigation. Since the introduction of DNA profiling in the mid-1980s, the forensic landscape has been reshaped. The sterility of the crime scene and its promised harvest of bio-trace evidence now seems sacrosanct - emphasised by the ghostly white suits of anonymous Scenes of Crime Officers working behind police tape in their protective tents.

Our tendency is to think of this attention to rigorous crime scene method as new, and linked to the exacting requirements of hunting for, preserving, and successfully analysing DNA evidence. We are certainly not inclined to think that modern CSI methods have their roots in fictional detectives such as Sherlock Holmes and Dr John Evelyn Thorndyke.

But, this is in fact the case. Detective fiction, alongside the instructional handbooks written by forensic practitioners, was responsible for the beginnings of crime scene investigation.

The crime scene

Hans Gross’s 1893 Handbook for Examining Magistrates is justly regarded as the first attempt to systematise the methods of crime investigation. Edmond Locard, the founder of Lyon’s pioneering police laboratory (1910), built on Gross’s work. Best known for his “exchange principle” and its pithy (though apocryphal) aphorism, “every contact leaves a trace,” Locard established modern, lab-based police investigation as dependent on trace evidence – matter, often invisible to the casual observer, that could serve as objective evidence.

For Gross and Locard, then, crime scene investigation centred on the disciplined search for minute, and ostensibly insignificant, trace evidence: blood, hair, fibres, and, most evocatively, what they called “dust”. As I have discussed in greater detail elsewhere, dust symbolised the furthest reach of the new forensic capacity that they were seeking to bring into being. What better way to illustrate the exacting requirements of crime scene investigation than to insist that every particle of dust be treated as a possible clue?

Early dust theorists recognised that they were engaged in a speculative venture, one that, compared to more traditional methods of investigation, would be met with scepticism. A viable forensics of dust entailed a radical transformation of the way that police officials and the public thought about and acted in the world they inhabited.

Crime fiction

The regime of CSI pursued by Gross and Locard was thus not merely a technical challenge. With this in mind, we can better understand the striking and multiple interactions between crime scene fact and fiction. The regime had to receive support from the wider police community and, indeed, the public.

As such, Locard regularly reached out to contemporary detective fiction as an ally in his campaign for a reformed police science. One particularly striking example is a 1924 text divided into two sections. The first is devoted to a survey of detective methods used by the fictional creations of Edgar Allen Poe, Émile Gaboriau and Arthur Conan Doyle, while the second refers to the exigencies of real scientific policing. In this book Locard happily confesses to having “taken from the adventures of Sherlock the initial idea of studying clothing dust and dirt stains”.

Dust analysis certainly features in the Holmesian cannon. Attention to cigar ash, the local characteristics of mud, and occupational dirt scraped from the fingernail certainly echo the Grossian and Locardian vision.

Dr John Evelyn Thorndyke

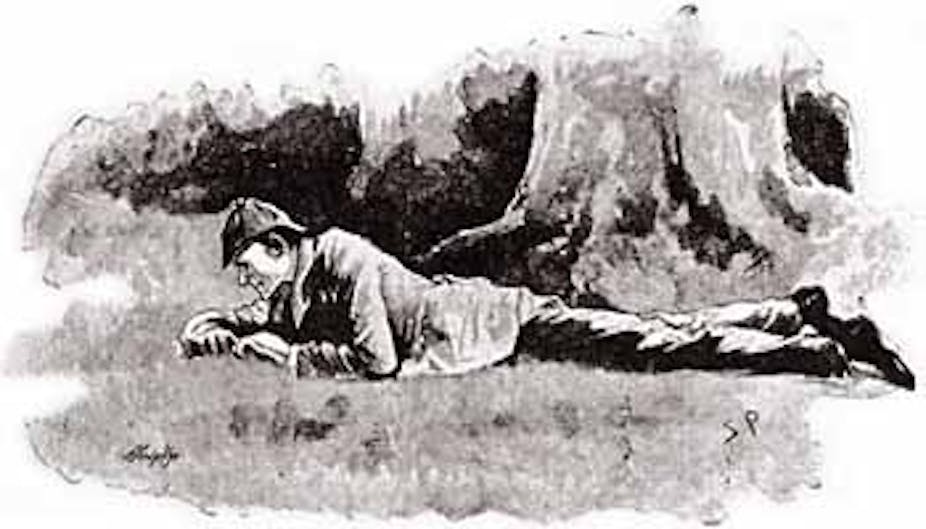

However, it was in the adventures of Holmes’s more rigorously scientific successor – Richard Austin Freeman’s character, Dr John Evelyn Thorndyke – that dust enjoyed its most systematic literary treatment. Explicitly positioned at the intersection of public education and public entertainment, Thorndyke’s adventures brought to a wide reading public the powers and possibilities of modern crime scene investigation.

Thorndyke replaced Holmes’s often eccentric deductions with ones grounded in “authentic” laboratory methods. His creator was thus pursuing an explicit pedagogic agenda aimed at instructing police officials and educating the public about the powers of modern CSI. To accomplish this, “realism” was key. In the preface to his first Thorndyke anthology, Freeman wrote:

“I have been scrupulous in confining myself to authentic facts and practicable methods. The experiments described have in all cases been performed by me, and the micro-photographs are from the actual specimens”.

As an apostle of forensic modernity, Freeman reflected and amplified the essentials of scientific CSI, and of dust’s place within it. “When it is discovered that a murder has been committed,” Thorndyke declares in one of his first adventures,

“… the scene of that murder should instantly become as the Palace of the Sleeping Beauty. Not a grain of dust should be moved, not a soul should be allowed to approach it, until the scientific observer has seen everything in situ and absolutely undisturbed”.

The value of this disciplined approach, Thorndyke pointedly observes, was a “lesson that the authorities still refuse to learn”. Dust drives the plots of numerous Thorndyke stories, in which the detective hero features as a meticulous and disciplined crime scene investigator, a virtuoso of microscopic analysis, and a master of reconstructive reasoning.

In doing so, his adventures brought the forensics of dust to a different, far broader, audience than that addressed by specialist texts. Freed from the constraints of technical realism, Freeman’s stories served as publicly accessible homilies on the world of hidden possibilities offered by properly managed trace-driven forensics.

This makes sense of the affinities between early crime scene theorists like Locard and their fictional counterparts: they were fellow travellers in a new speculative venture, one that we as consumers of contemporary CSI tend to take for granted.

When you next see in your newspaper or on your TV screens an image of a modern crime scene, with its protective tents and its ceremonially cloaked guardians, think of it as Thorndyke’s “Palace of Sleeping Beauty,” come to life.