Environment minister Greg Hunt’s pledge to appoint a threatened species commissioner is a bright spot on an otherwise pretty bleak conservation landscape.

Hunt described the “deep challenge” of species loss since European settlement, since when he said at least 10% of our land mammals (and many other creatures too) have died out.

However, with the cooperation of both sides of politics, the minister (and future ministers, for that matter) is on the verge of being granted legal immunity from challenge to any mining approvals he makes that impact on species conservation.

Let’s hope he thinks again before removing the possibility for such challenges.

What we need is respect for our natural landscape, and the plants and animals that have called it home for millions upon millions of years, to be woven into the fabric of our national consciousness.

Deep time beginnings

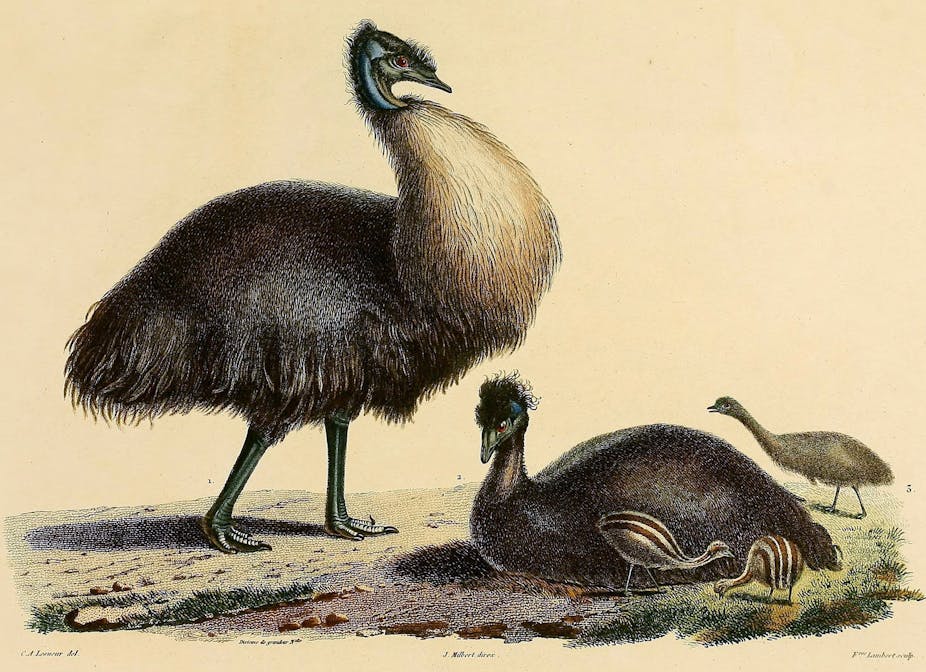

Picture the scene: a summer’s day in the Eocene epoch, 45 million years ago. A seaway that has been invading the rift valley between Australia and Antarctica over the preceding 110 million years finally breaks through somewhere near the Tasman Rises (which back then was at a latitude of 60 degrees south). For the first time, the narrow sand bridge between the two sides remains underwater at low tide, making it impossible to walk between the two continents without getting your feet (well actually, your claws) wet. A couple of Mihirungs - giant flightless birds - stroll past, perhaps not realising the portentousness of the moment.

The following week, a severe storm breaks a sizeable channel through the berm. Australia cuts loose and a continent is born.

Few have any notion of an Australia without us. Judging by the average Australia Day rhetoric, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the place didn’t exist before our arrival - that the land itself was some incidental substrate for human culture. Yet the real story of Australian habitation – by plants and animals, if not yet people – began with that moment 45 million years ago. It would be at least another 44.925 million years before the first humans arrived on the scene (and then, of course, another 750 centuries until 1788).

Here was an isolated chunk, worn out, adrift in immense oceans - a land which one bleary air traveller reputedly bagged as “the only place in the world 24 hours from anywhere”. So weird did the place and its plants and fauna strike the English in the late 18th century that some even got to thinking it had been formed from a chunk that had fallen off the sun.

The colonies eventually thrived. But still, over the paddock fence was this “other Australia” – a living land (and its surrounding oceans) that has endured for those 45 million years but which, from many perspectives, is now damaged beyond repair.

The life-forms, physical landscapes and ecological systems it nurtured over that time gave rise to the Australia found by successive waves of human immigrants - an inestimable gift from deep time. In a very real sense, the genomes of Australia’s contemporary native plants and animals are an encoded treasure trove of the land’s prehistory - they have the continent’s millions of years of evolution hardwired into their paws, beaks and twigs.

Unbalancing the biota

Australia’s closely linked communities of plants and animals lived life here to the full. They shared boom times, horrible lean times, co-operating to make a fist of it, but often pitted against one another in a bitter struggle for survival, some sliding into cruel extinction. Successive waves of European immigrants then trampled the modified ecology of this continent as if scrambling for bargains in the first tumultuous minutes of the Boxing Day sales – a process portrayed by Mary E. White as “unbalancing the biota”.

Speaking on the ABC’s Catalyst program celebrating the 2013 Eureka Prizes, Professor Michael Archer observed:

“We don’t value Australian animals, plants. Somehow we think we can obliterate the living things of the planet, and that’s ok… As long as we’ve got cows and chickens, what’s the problem? If we allow the biodiversity to continue to erode the way it’s going now, it’s us that’s gonna collapse. I’m trying to find another planet to live on.”

Constitutional recognition

Commendably, the Constitution is currently in the process of being amended to recognise Australia’s indigenous people.

Perhaps we might also take the opportunity to write in some form of ecological protection – a sort of bill of rights for the country’s biodiversity.

Here is a suggestion:

The Commonwealth of Australia celebrates the wondrous ecology of Australia, the value of its land and surrounding seas, and recognises the right of species to exist in a sustainable way in all its natural regions.“

The Commonwealth government could then be given the power to delineate Australia’s natural regions in which ecological sustainability should prevail.

Such recognition would counter the proposed watering down of the EPBC Act, which looks set to pass with the support of both major parties. Is it too much to ask for a similar spirit of cooperation in any constitutional move to enshrine protection of Australia’s ecological landscape? The global benchmark here is unquestionably Costa Rica’s pioneering legal protection of natural wealth.

This proposition might seem novel, and granted there are more pressing constitutional issues to address first. But at the end of the day we should not settle for lives in lost or degraded landscapes, let alone a diminution of the invaluable services to the economy that Australia’s natural capital provides.

We already acknowledge that our land abounds in nature’s gifts. It’s time to expand our moral circle and grant due recognition to what is left of its extraordinary biodiversity.