In the film industry, research is commonly understood as audience research. Films, in contrast, are entertainment or a form of audiovisual communication. But can film-making also be a form of academic research?

Within the academic community, research is about new knowledge and is done through experiments or surveys, not through the creative process of film production. But it is also done using interviews and ethnographic observation.

Many people can accept that making a documentary film involves activities commonly associated with research, such as the systematic investigation of a question or problem.

But what about a fiction film, a drama or a comedy? Or even a TV soap opera? That may be going too far.

While there have been recent moves to recognise creative works as research outputs, films are more commonly seen as a way of communicating other people’s research, rather than a research activity in their own right.

Unlike the Australia Council for university-based artists, state and federal government screen-funding bodies have been reluctant to fund productions occurring in universities, using a “double dipping” argument that makes little sense in the absence of this work being funded anywhere else.

Funding from the Australian Research Council has also proven difficult in the past for creative film projects, competing against well-established fields of research in the sciences and humanities.

Film-maker/ academics are caught in the middle, wishing to develop their knowledge of their field through their creative practice but without appropriate funding, publication opportunities, institutional support or wider recognition.

This also feeds one of the main objections to claims for film-making as research, that it is a contrived attempt by filmmaker/ academics to access research funding to meet university pressures for research performance. Unfortunately, this objection carries more weight in the absence of a clearly articulated position by filmmaker/ academics on the arguments supporting their claims.

The discussion about film-making as research often focuses on distinctions made between creativity and knowledge, or between the emotional and rational dimensions of human experience.

But it could also be argued this is a side-issue that focuses too much on the film medium’s ability to convey content.

Both fiction and non-fiction films are always “about” something and it is tempting for non-filmmakers to reduce the creative work to this content – a story or subject matter abstracted from the work on the screen. But in many cases that’s not where the research is located.

The academic peers who evaluate whether any film work contributes knowledge to the field of film production should be other film-makers, who do so on the basis of how effective the work is in exploring and extending our knowledge of the potential of the medium.

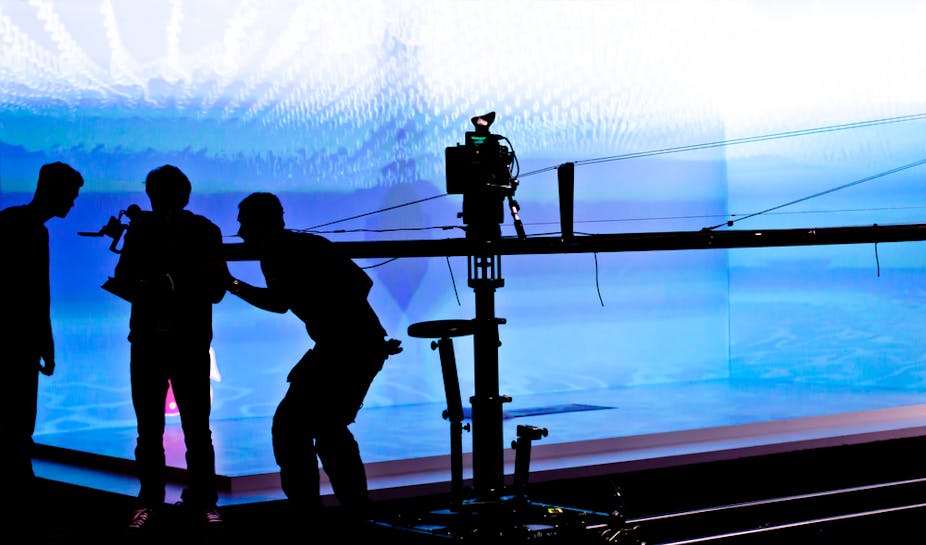

This knowledge of the medium could be in relation to the film’s use of images and sound to tell a story, formal and stylistic experimentation, the use of new technology, production techniques, platforms or many other possibilities. It could be in relation to the production process and not apparent in the final work at all, such as the use of innovative business models, methods of working with actors or the many other production personnel involved.

Another contested issue that often clouds the debate of film-making as research is the use of audiovisual expression over written language in communicating the research.

Proponents argue it is appropriate to communicate research in the language of the field and this offers possibilities for conveying human experience in new ways that deepen and extend understanding, while critics query the perceived ambiguities of meaning that seem to flow from visual communication.

It is often asked whether a film can make an argument. I would argue that in some cases it clearly can but it is incumbent on practitioners in the field to provide evidence of the various ways this can be achieved, which arguably has not occurred to the extent required.

Many academic filmmakers believe they have fallen between the cracks in relation to research funding, a situation that is impeding the development of the field. To rectify this situation requires advocacy by the discipline, articulating its position with greater clarity and depth.

The broader academic community and the screen production industry also need to recognise that research into the creative practice of screen production has much to offer – developing innovation in the screen industries and the ability of screen production to enhance our understanding of the complexities of human experience, in all its dimensions.

The majority of our universities have popular undergraduate and postgraduate courses in screen production. Film, television and other media production is a large, viable and significant higher education sector, feeding graduates into employment in an increasingly audiovisual world.

Yet without a corresponding research sector, the discipline seems like a body without a head.

Many of these issues will be explored at Sightlines, a hybrid film festival/ conference being held at RMIT University on November 23-25.