According to an experimental study published in Nature Communications, severing key nerves in the neck may provide a new option for lowering high blood pressure.

Considering new approaches to treating high blood pressure (hypertension) is crucial. High blood pressure is a very common and important cause of disease and death resulting from problems with the heart, and with the blood vessels in the body and brain.

Treatment to lower high blood pressure is supposed to continue for decades. However, even by 12 months after the starting treatment, around 50% of patients are not taking their tablets regularly, if at all.

Some patients are drug intolerant of many classes of blood-pressure lowering treatment. And even for patients who take their medicines regularly, blood pressure control is not guaranteed.

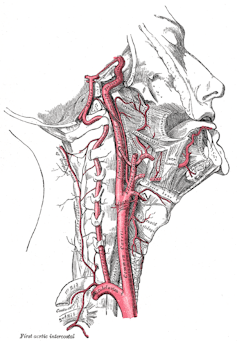

There are two main carotid arteries, one on each side of the neck. There is a widening of each carotid artery (the carotid sinus), where the artery branches to supply blood either to the face or the brain. The carotid sinus is an important site for baroreceptors, which are specialised pressure detectors in blood vessels and in the heart. These receptors regulate blood pressure by modulating neural pathways.

Several innovations using devices and other non-drug treatments have recently been developed. Using an electrode to stimulate the carotid sinus, for example, has been explored as a potential treatment for high blood pressure.

Further research in this area has initially suggested very promising results. This research concentrates on the carotid body.

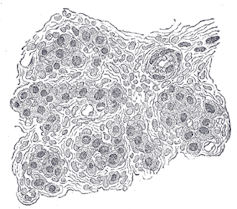

On each side of the neck there is a carotid body, a small nodule, about the size of a grain of rice, that lies by the artery next to each carotid sinus. It is tissue that detects changes in the composition of the arterial blood that runs through it, assessing blood oxygen, carbon dioxide, temperature and pH.

By removing nerves from this tissue through neck surgery, the new study posits that it is possible to interrupt signals from the carotid body to cardiovascular control centres in the brain, and therefore better regulate blood pressure.

Hypertensive rats

The team of researchers used a genetic form of high blood pressure in rats. This allowed them to explore the effects on blood pressure of interfering with neural regulation of the circulatory system, and the kidney.

They compared the response to removing clusters of nerves from a carotid body on one side of the neck, with removal of these nerves on both sides of the neck.

They also compared the effects of removing nerves from the carotid body alone with removing nerve supply for the kidneys. And they assessed the combined effects of removing nerves to and from the kidneys, and from the carotid body.

In their experiments, they found that removing carotid body nerves from both sides of the neck led to a large fall in blood pressure. However, there were no effects of removing nerves only from the left or right carotid body.

In humans?

We should, however, be cautious over these results. Earlier promise of large blood pressure falls from removing nerves from the kidneys in human hypertension was not supported in a recent study presented earlier in the summer.

And of course, the research in question involved rats. The response in humans is likely to differ. Could carotid body denervation could be an effective and safe option for humans, and therefore provide long term treatment benefit?

There are of course technical risks for any invasive procedure – including adverse effects of anaesthesia, bleeding, infection, and damage to surrounding structures such as other nerves and vessels.

Unlike drug treatment, effects of removing nerves from the carotid body, if greater than desirable, or associated with troublesome complications, could at best be reversed only very gradually - and then only in those patients in whom the nerve supply from the carotid body grows back.

Another option could be the denervation of the carotid body by a catheter which can apply local heat to damage nerves, using energy from radio waves emitted by a transmitter at a catheter tip fed into the carotid sinus. This has been evaluated in the case of kidney arteries and to treat disorders of heart rhythm. While less invasive than surgery, risks from this catheter approach would include causing stroke syndromes from damage to the carotid artery lining, or dislodging pieces of cholesterol or clots from the artery lining.

If successful, the procedure would be likely to be used only in older patients with severe hypertension. However, these patients are more likely to have established clinical vascular disease, and more likely to have significant co-morbidity in heart and brain. They are therefore more vulnerable to acute changes in blood flow that may result from the procedure.

In brief, there will be important questions to be resolved about the clinical and cost benefit of a largely irreversible and potentially hazardous procedure, in real world patients likely to have significant co-existing disease.