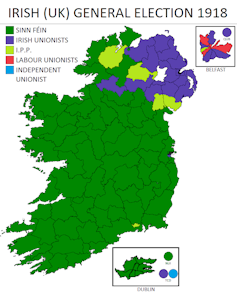

The 1918 election is probably best known in Britain as being the first election in which women could vote. In Ireland, it is remembered for something quite different. The general election in December that year saw Sinn Féin – a revolutionary independence party, which had not contested the previous general election – win 73 out of 105 seats in Ireland.

It’s long been thought that Sinn Féin’s dramatic victory was, in part, due to major changes to the Irish electorate. In early 1918, the right to vote was extended to all men over 21 and most women over 30. Ireland, at the time still part of the UK, saw its electorate grow from less that 700,000 to more than 1.9m.

With a near tripling of the electorate and a landslide victory of a new, radical political party occurring in the same year, scholars have long assumed that the two were linked: that Sinn Féin experienced it’s very own “youthquake”, just like the UK’s Labour party, which also benefited from a surge in turn out among young people, almost 100 years later. But our new research challenges this assumption.

A radical upset

This Sinn Féin victory ushered in an era of revolution. The previously dominant and more moderate party of Irish nationalism, the Irish Parliamentary Party, was decimated, and returned just six of the 67 seats they held prior to the vote. And within two months of the election, Sinn Féin’s MPs had declared independence from the UK, and the armed conflict that would become Ireland’s War of Independence began.

On the eve of his party’s crushing electoral defeat, William Doris, an Irish Parliamentary Party candidate, lamented:

On the old register we were perfectly safe and the question is how the extended franchise will affect us. I am satisfied that a majority of the women over 30 will be with us, but the vast majority of the boys from 21 to 30 will be against us. They appear to have gone mad and no doubt we will have all kinds of intimidation, personation and so on.

This longstanding view has not been extensively tested – until now. To examine the impact of the voting reforms on the 1918 election results, we combined the results of the election for each constituency in Ireland with information on the number of new male and female voters. We also constructed an economic and social profile of each constituency, by collecting information on things such as occupation, literacy and religion from the 1911 census.

A statistical analysis of this information failed to uncover a link between the number of new male voters in a constituency and support for Sinn Féin. Where there were more women voters, however, support for Sinn Féin appears in fact to have been lower.

This is not perhaps surprising: the restrictions on women’s voting rights meant that younger women and those who failed to meet the property requirement - those who were not rate payers or wives of rate payers - were still denied a voice. Indeed studies of Britain suggest that the Conservatives were the main beneficiaries of the new women’s vote. Our research found that in Ireland, women may have been less likely than men to use their vote at all.

Rising up

It’s impossible to know for sure how individuals voted in 1918. But our findings suggests that new voters did not, by themselves, propel Sinn Féin to power in Ireland. Other factors must have played a bigger role than previously thought. The legacy of the Easter Rising is a strong contender, with public opinion appearing to shift sharply in support of the rebels following the British crackdown.

Read more: Six days that shook the world: how the Easter Rising changed everything

The conscription crisis of 1918 may also have had a big impact. Conscription had been enacted in Britain in 1916 and the German offensive of 1918 had induced the cabinet to finally extend conscription to Ireland. The attempt to introduce conscription in Ireland was, of course, deeply unpopular.

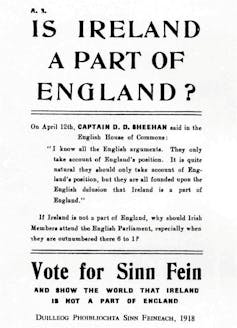

Although all strands of Irish Nationalism were united in opposition to conscription, it was Sinn Féin who claimed the role of the most forceful opponent of conscription. As such, Sinn Féin’s electoral success was more likely driven by a change of heart within the Irish electorate, more than a change of composition.

It’s perhaps no surprise that religion was a strong predictor of support for both the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party and more radical Sinn Féin, since both were nationalist parties. Better agricultural land was associated with a lower Sinn Féin vote, suggesting perhaps that wealthier farmers may have disliked Sinn Féin’s more radical approach. And higher levels of women in work and female literacy were associated with higher turnout overall.

It is clear that the events between 1916 and 1918 led large numbers of people to abandon support for the Irish Parliamentary Party and back the more radical form of nationalism offered by Sinn Féin. Even without a change in the franchise, the election of 1918 would still have marked a turning point in Irish history.