This weekend Mars appears at its best and brightest. It reaches opposition on Sunday, May 22, which means the planet will appear opposite the sun as viewed from Earth and it brings Mars closest to Earth for the next few weeks.

It’s quite striking to see the red planet in the southeast at sunset, shining with a bright and steady glow. In fact, Mars is looking brighter than we’ve seen it since November 2005.

Mars is positioned near the head of Scorpius, a magnificent constellation which can be found rising in the southeast at this time every year. It’s always a fantastic one to look out for; the bright star pattern spans a relatively large patch of sky and it doesn’t require too much imagination to turn the pattern into a scorpion.

Below Scorpius, there’s a point of yellowish light that, like Mars, shines steadily in contrast to the twinkling light of the stars. That’s the planet Saturn, which also happens to be approaching opposition. Saturn will sit opposite the sun on June 3.

And not to be left out, the full moon passes through this patch of sky from Saturday to Monday, May 21-23. We don’t often describe it this way, but the moon will be in opposition too.

Opposition for best viewing

When an object, like Mars, Saturn or the moon, reaches opposition we get to see it at its very best.

As the sun sets, an object that is at opposition will rise. That’s why this weekend Mars, Saturn and the moon are clustered in the southeast, as the sun is setting over in the northwest. We will see them all for the entire night, from sunset to sunrise.

Furthermore, around the time of opposition a planet will make its closest approach to Earth. The planet has a moderate increase in size, which makes it appear brighter than at any other time.

Of course, this is doesn’t apply to the moon on its monthly orbit around the Earth. There’s a few times each year that the moon’s closest approach (or perigee) coincides with the full moon but most often that’s not the case.

What is special for the moon at opposition is that the sun lights up the entire face of the moon, making it full and therefore shining at its brightest.

Far away and close again

Mars will come closest to Earth on May 30, at a distance of 76 million km. Its closest approach isn’t exactly aligned to opposition because of the eccentricity of Mars’ orbit. It also means that for about the next three weeks Mars will remain lovely and bright.

It’s quite a favourable opposition this year, although the next opposition of Mars in July 2018 will be even better. The planet will be almost 20 million km closer and will shine around twice as bright.

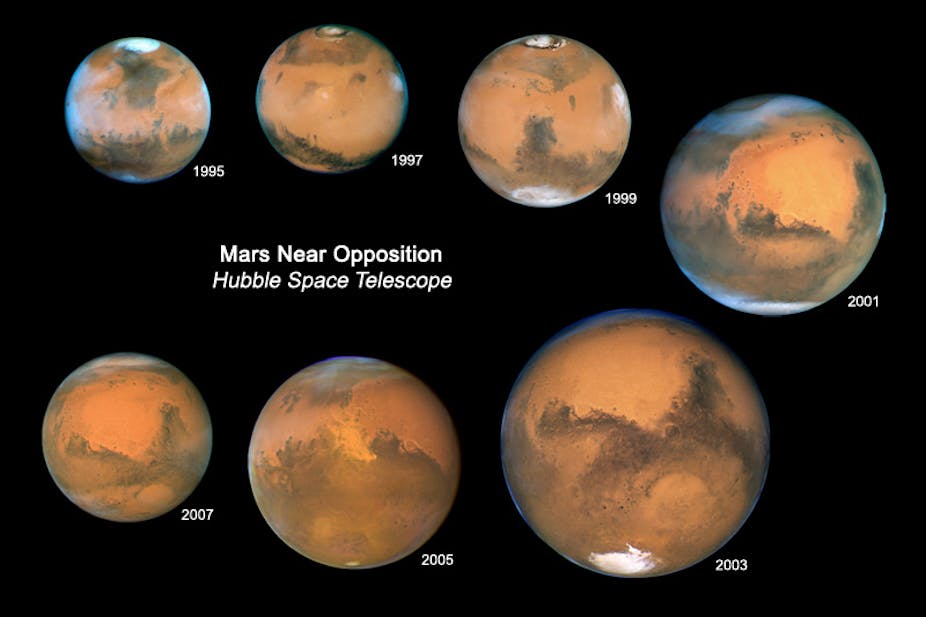

Opposition has a particularly great effect on Mars, because it is Earth’s neighbour and it has the most eccentric orbit of all the planets. A close approach of Mars can vary by almost 50 million km between the most favourable opposition to the least favourable.

Earth goes around the sun twice as fast as Mars, so a Mars opposition occurs every 26 months. On the other hand, Saturn takes a leisurely 29.4 years to orbit the sun, so the Earth meets up with Saturn every 13 months (Earth has made a full lap of the sun, while Saturn has barely moved).

At present, Saturn is going through some unfavourable oppositions, as it is approaching aphelion (or furthest from the sun) in 2018. It’ll be about a decade before Saturn moves close enough to Earth for it to shine particularly bright once more.

However, its magnificent rings are currently in an open configuration making a fantastic sight for small telescopes.