It sounds very familiar – a well-respected monarch dies, and a radical, left-leaning, Antipodean cartoonist struggles to find the right tone to commemorate the event.

He is torn between his distaste for what he sees as the archaic, pre-modern institution of monarchy, and the undoubted personal quality of the late incumbent.

More used to poking fun at the great and good, or attacking governments for their weak-willed or wrong-headed policies, changing tone to reverence and respect is difficult.

But in the end, he manages to strike a very good balance and produce a memorable cartoon.

The well-respected monarch was George VI; the radical, left-leaning, Antipodean cartoonist was David Low; and the year was 1952. With From One Man to Another, Low not only conveyed his own respects, man-to-man, but imagined also the British workman, his hat in his hand and sleeves rolled-up, casting a humble bunch of flowers towards a mighty tombstone labelled “The Gentlest of the Georges”.

This was an expression of democratic – even socialist – sensibility, in an age when monarchy seemed, to many, to be increasingly out-of-step with the advance of modernity and the inexorable march of post-war history.

Low was compelled to look back, not forward, conscious he had an historic role to fulfil in commemorating the passing of the king who had embodied so much of the stolid, British pluck and humility during the second world war.

He reflected in his 1956 autobiography that he hated the old-fashioned, “The Nation Mourns”-style of Victorian cartoon, but it was to that set of images and traditions that he turned.

Read more: 16 visits over 57 years: reflecting on Queen Elizabeth II's long relationship with Australia

A long lineage

Cartoonists have had to do something similar in 2022, with the death of Queen Elizabeth II.

In the United Kingdom, the likes of Peter Brookes, Ben Jennings and Christian Adams have all been conscious of the need for solemnity, as well as celebration.

Across the world, cartoonists have had to struggle with much the same thing, and some favoured themes are already apparent: Elizabeth reunited with her husband, the Duke of Edinburgh, or troops of sad corgis; the Union Flag with an Elizabeth II-shaped hole at the centre; or a tube train with a sole occupant heading into a blaze of light at the end of the tunnel.

All of these images speak to the style and the visual language of today, but also share a lineage several centuries old.

Read more: The New York Times ends daily political cartoons, but it's not the death of the art form

A bereaved widow, again

Nobody would have thought to depict Queen Victoria’s death in 1901 with her travelling to heaven by tube, although the Underground seems emblematic of her age (London’s first underground railway was opened in January 1863, 26 years into Victoria’s reign).

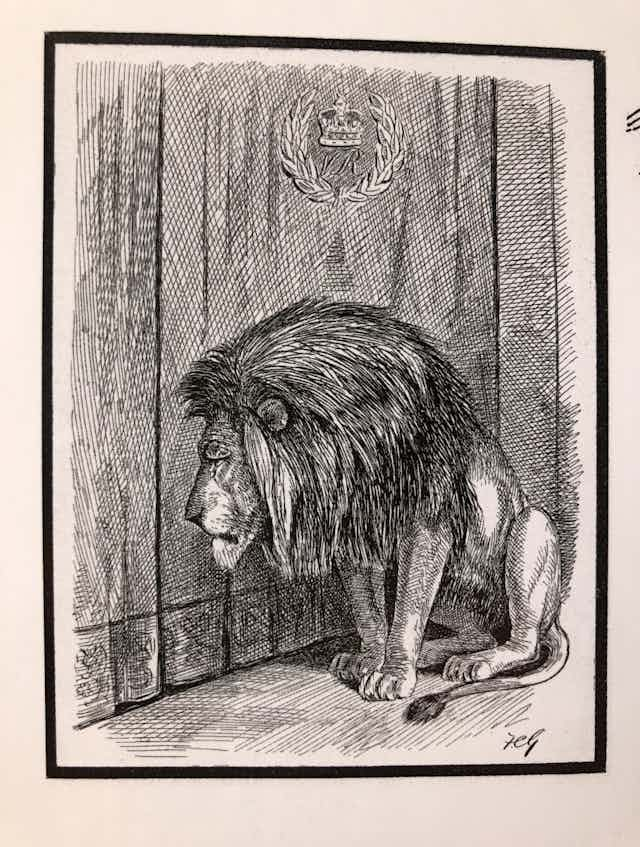

There were no sad corgis (that breed only became associated with the Royal Family from the 1930s), but a downcast British Lion was imagined by Francis Carruthers Gould in Fun.

The theme of a bereaved widow finally reunited with her spouse is clearly a parallel (Albert, the Prince Consort had died in 1861). So too is the very idea that a cartoonist should commemorate the event – something unthinkable when William IV died in 1837, or so much so when George IV died in 1830 that a well-known cartoonist never published his draft sketch.

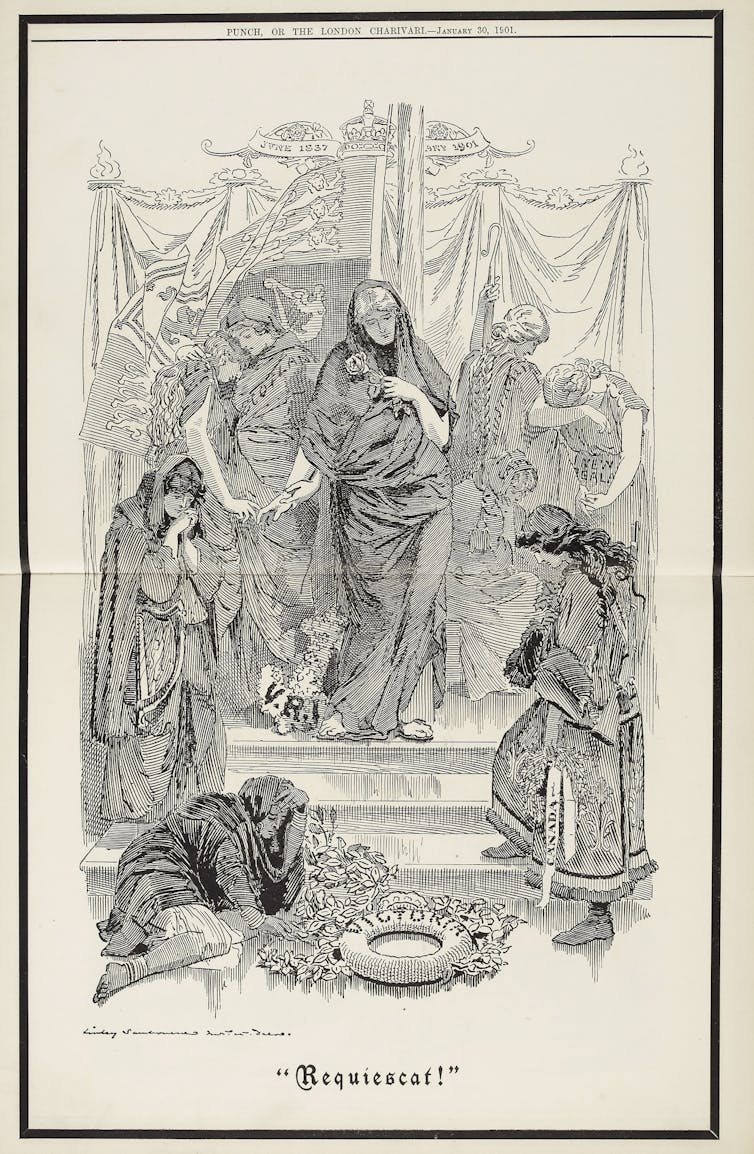

The sheer immensity of the loss of Victoria called for some pretty special treatment, at a time when cartooning was a lot more formal and respectable than it is today.

It preoccupied several days’ work for Linley Sambourne, chief cartoonist of London’s Punch (for a while, a magazine that was almost as much a British institution as the monarchy).

Requiescat was huge: a double-page spread in sombre black-and-white, depicting a gaggle of goddesses in mourning for their lost monarch.

Allegorical female figures representing countries were all the rage in Victorian and Edwardian cartooning (something David Low also hated and thought was “moth-eaten” by the time he was at his peak).

England, Scotland, Wales, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and India were all included by Sambourne.

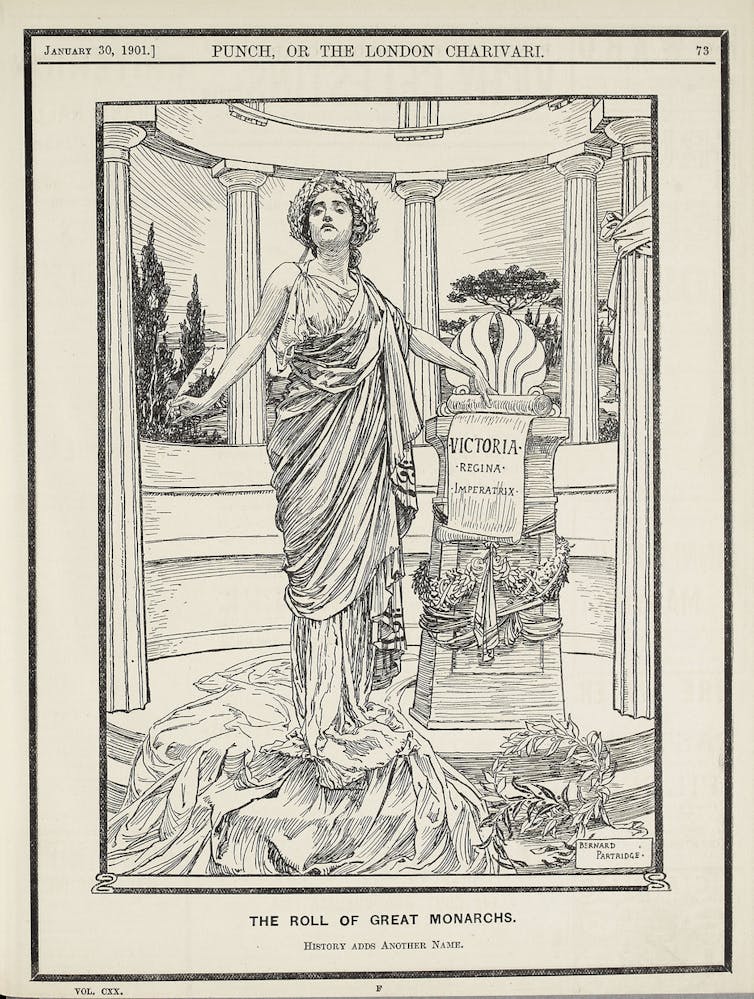

Just one goddess was enough for his junior colleague, Bernard Partridge, who imagined Clio – History herself – adding the name of Victoria to the roll of great monarchs.

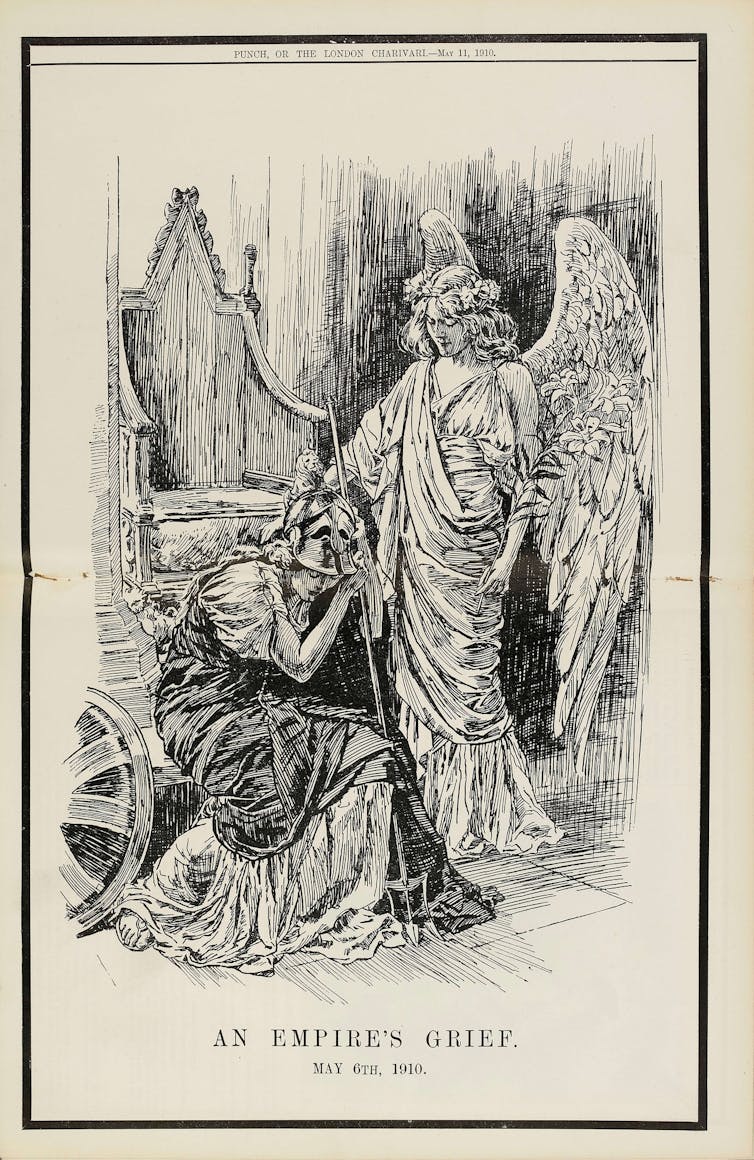

It was the same when Victoria’s son and heir, Edward VII, died in May, 1910.

Bernard Partridge went with just two figures, rather than a whole host, imagining a weeping Britannia seated before the empty Coronation Chair, an angel of peace reaching out to touch her shoulder.

This was designed to express “an empire’s grief” in terms even more explicit than Sambourne had done with Victoria, but the imagery was very British; even domestic.

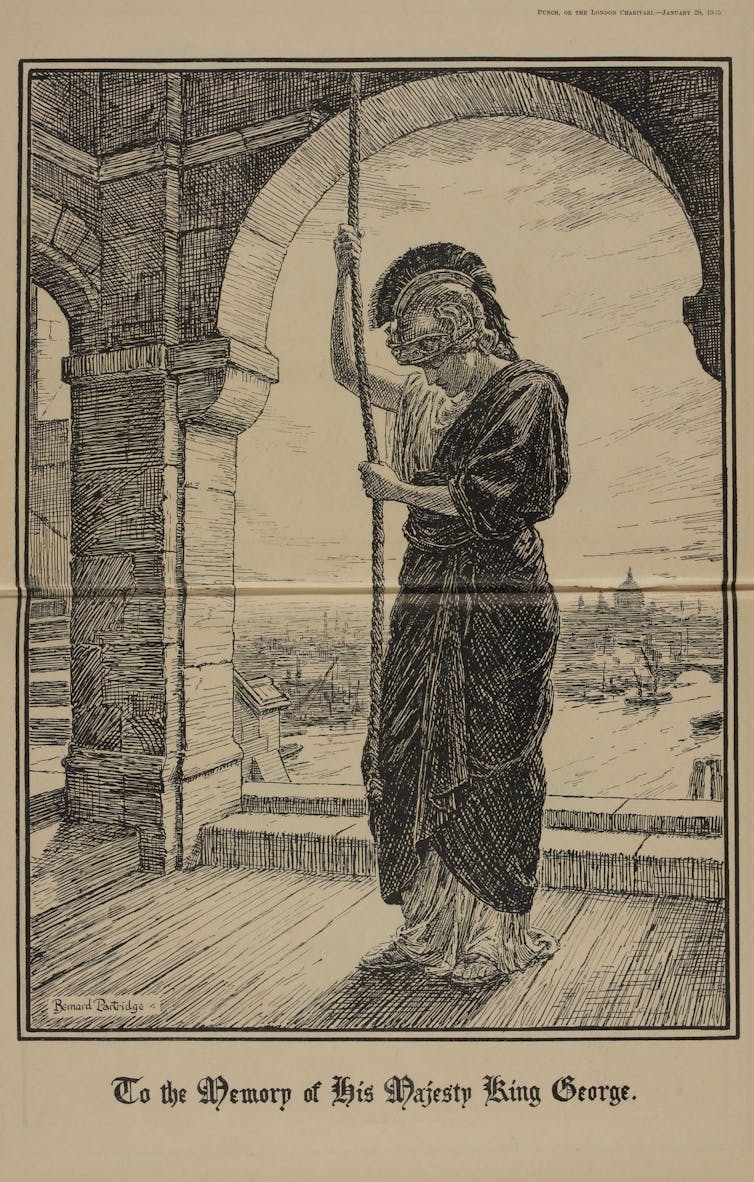

Minus the caption, it could almost be recycled in 2022 - crucially, the monarch does not actually appear. So too, Partridge’s offering in January 1936, when George V died (apparently by the hand of his doctor).

Britannia tolling a bell from a medieval bell-tower, with a fog-laden London skyline in the background. Clear the fog, add a Gherkin and a Shard, and the effect would be much the same.

While David Low struggled against the Victorian style of memorial cartoon, it is still very much with us. As so often, cartoons can encapsulate a whole host of feelings that mere words can’t express.