What are we to make of the results of the 2014 South African elections? On one level, it was largely predictable: the ANC was always going to lose some support, but not enough to please the opposition; the Democratic Alliance (DA) was always going to grow its share, but was never going to to top its performance in 2011.

Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) made a respectable showing – fairing far better than fellow newcomer Agang, wrecked by a disastrous aborted “marriage” with the DA. The Congress of the People (COPE), riven by leadership squabbles, was predictably decimated, and the ongoing decline of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) saw it lose its status as the official opposition in KwaZulu-Natal.

On the face of it, all reasonably predictable outcomes. But on another level, the results sent important signals about South Africa’s political system and its electorate – signals that both the ruling party and the opposition movement would be foolish to ignore.

Warning from Zimbabwe

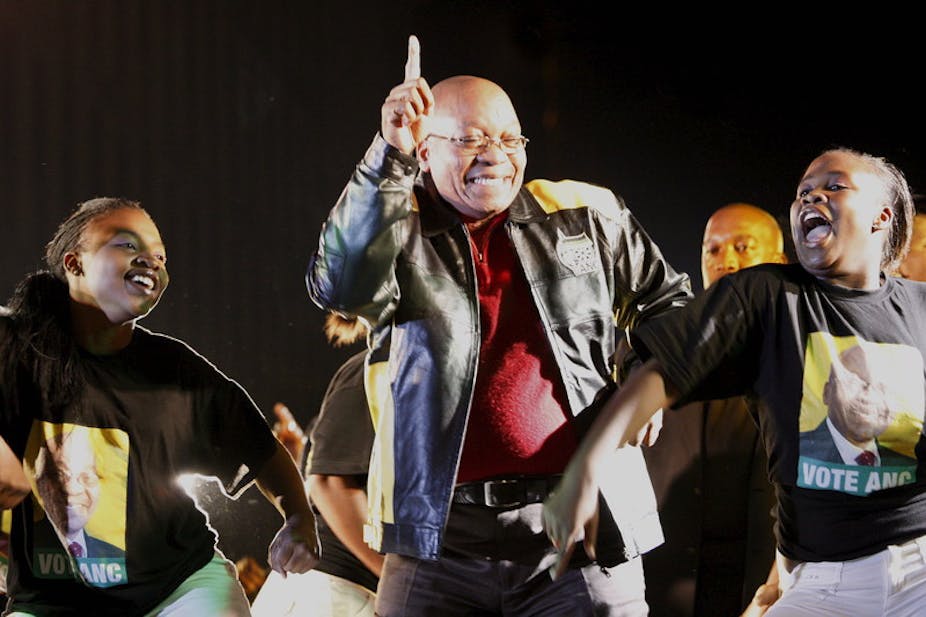

The ANC’s 4% decline should be a wake-up call for the ruling elite, especially after the 4% decline it saw in 2009. If this is not enough, the scare in Gauteng province, which it only narrowly retained (winning only 54%, down from 64%), should shake it from its complacency. Otherwise it runs the risk of degenerating into an organisation like Zimbabwe’s ZANU-PF: retaining a firm base in rural areas, while losing the metropolitan areas, the middle classes, and the intelligentsia – including the black intelligentsia (or “clever blacks”, as Zuma has called them).

Until now, the ANC has been complacent about its support. That much was evident in its silly statement that only the middle class cared about the Nkandla saga. Forget the class chauvinism of the suggestion that poor people are not angered by corruption and unethical behaviour; the claim is empirically blinkered.

It cannot explain the respectable showing of the EFF, the fall in turnout from 77% to 73% between 2009 and 2014, the 8m people who have not bothered to register, or the fractures in the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) – including the refusal of NUMSA, the largest union, to endorse the ruling party.

The only reason the ruling party has not fared worse is because many voters have not found a credible alternative among South Africa’s existing opposition parties. Had such an alternative existed, the ANC’s support would have declined far more significantly.

This raises the second important signal from the election results. The relatively strong showing of the EFF suggests that the electoral gap in South Africa is not to the right, but rather to the left of the ANC. This is what many parties like the DA and Agang have not truly understood.

Instead, their leaders assume that building an opposition merely requires exposing the ruling party’s corruption and governance failures. But South Africa’s voters are far more sophisticated than opposition leaders and mainstream commentators give them credit for.

They are not reluctant to vote for the DA because of the racial pigmentation of the DA leader; they are reluctant because these parties still seem to represent the values, aspirations and interests of the richer portions of society.

Various subtle but strong messages convey this. For example, both parties rely on private sector economists to buttress their arguments; both failed to visit Marikana after the massacre there. Poor people are therefore confronted with a dilemma: vote for a party prone to corruption and efficiency deficits, or for one whose ideological interests seem diametrically opposed to theirs. After a rational calculation, they still opt for the devil they know.

Gap on the left

The EFF might seem like the logical choice for these voters, but its support is built principally on protest voting. Many citizens do not take Julius Malema seriously. EFF voters do not vote for him because they think he’s a credible president; they vote for him to spite the ANC, and to send a message to the ruling political elite.

In a lot of ways, the vote for the EFF is what Ronnie Kasrils was calling for: a protest vote reflected not in a spoiled ballot, but in an actual vote for the ANC’s prodigal son.

But all this could change if a more credible electoral alternative were to emerge – and this is no longer as far-fetched as it may have been in previous years. NUMSA, COSATU’s largest union, did not endorse the ANC in this election, and it has already signalled that it is exploring the possibility of forming a political party.

The hypothetical new party would have all the prerequisites of a serious electoral alternative: a liberation pedigree, a national organisation capable of mobilising people, financial resources (through the control of union companies and pension funds), and most importantly, an ideological position to the left of the ANC. For the first time then, South Africa’s poor – the bulk of the electorate – would have a real electoral alternative.

This is what the ANC most fears, and rightly so, since it would be the single biggest threat to its grip on government. In the absence of any such threat, as has been the case in South Africa, the political elite has no reason to act in citizens’ interest. When such a threat is real, accountability is established, and there is an incentive to genuinely respond to the interests of the voting population.

All this suggests that 2014 was merely the curtain-raiser for the real game: the 2019 elections. This is when electoral history might be truly made in South Africa. But that is not inevitable; it depends on what happens in COSATU, whether NUMSA decides to form an alternative to the ANC, and whether the leadership of the ruling party remains as complacent as it has apparently become.

It is also dependent on whether South Africa’s political actors, in both government and opposition, have the courage to face hard choices and difficult trade-offs. Only then will they offer the possibility of genuinely inclusive and democratic change.