In our sexual histories series, authors explore changing sexual mores from antiquity to today.

It was a well-kept secret among historians during the late 19th and early 20th centuries that the practice of magic was widespread in the ancient Mediterranean. Historians wanted to keep the activity low-key because it did not support their idealised view of the Greeks and Romans. Today, however, magic is a legitimate area of scholarly enquiry, providing insights into ancient belief systems as well as cultural and social practices.

While magic was discouraged and sometimes even punished in antiquity, it thrived all the same. Authorities publicly condemned it, but tended to ignore its powerful hold.

Erotic spells were a popular form of magic. Professional magic practitioners charged fees for writing erotic charms, making enchanted dolls (sometimes called poppets), and even directing curses against rivals in love.

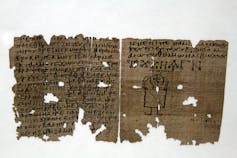

Magic is widely attested in archaeological evidence, spell books and literature from both Greece and Rome, as well as Egypt and the Middle East. The Greek Magical Papyri, for example, from Graeco-Roman Egypt, is a large collection of papyri listing spells for many purposes. The collection was compiled from sources dating from the second century BC to the fifth century AD, and includes numerous spells of attraction.

Read more: In ancient Mesopotamia, sex among the gods shook heaven and earth

Some spells involve making dolls, which were intended to represent the object of desire (usually a woman who was either unaware or resistant to a would-be admirer). Instructions specified how an erotic doll should be made, what words should be said over it, and where it should be deposited.

Such an object is a form of sympathetic magic; a type of enchantment that operates along the principle of “like affects like”. When enacting sympathetic magic with a doll, the spell-caster believes that whatever action is performed on it – be it physical or psychic – will be transferred to the human it represents.

The best preserved and most notorious magical doll from antiquity, the so-called “Louvre Doll” (4th century AD), depicts a naked female in kneeling position, bound, and pierced with 13 needles. Fashioned from unbaked clay, the doll was found in a terracotta vase in Egypt. The accompanying spell, inscribed on a lead tablet, records the woman’s name as Ptolemais and the man who made the spell, or commissioned a magician to do so, as Sarapammon.

Violent, brutal language

The spells that accompanied such dolls and, indeed, the spells from antiquity on all manner of topics, were not mild in the language and imagery employed. Ancient spells were often violent, brutal and without any sense of caution or remorse. In the spell that comes with the Louvre Doll, the language is both frightening and repellent in a modern context. For example, one part of the spell directed at Ptolemais reads:

Do not allow her to eat, drink, hold out, venture out, or find sleep …

Another part reads:

Drag her by the hair, by the guts, until she no longer scorns me …

Such language is hardly indicative of any emotion pertaining to love, or even attraction. Especially when combined with the doll, the spell may strike a modern reader as obsessive (perhaps reminiscent of a stalker or online troll) and even misogynistic. Indeed, rather than seeking love, the intention behind the spell suggests seeking control and domination. Such were the gender and sexual dynamics of antiquity.

But in a masculine world, in which competition in all aspects of life was intense, and the goal of victory was paramount, violent language was typical in spells pertaining to anything from success in a court case to the rigging of a chariot race. Indeed, one theory suggests that the more ferocious the words, the more powerful and effective the spell.

Love potions

Most ancient evidence attests to men as both professional magical practitioners and their clients. There was a need to be literate to perform most magic (most women were not educated) and to be accessible to clients (most women were not free to receive visitors or have a business). However, some women also engaged in erotic magic (although the sources on this are relatively scarce).

In ancient Athens, for example, a woman was taken to court on the charge of attempting to poison her husband. The trial was recorded in a speech delivered on behalf of the prosecution (dated around 419 BC). It includes the woman’s defence, which stated that she did not intend to poison her husband but to administer a love philtre to reinvigorate the marriage.

Read more: Elite companions, flute girls and child slaves: sex work in ancient Athens

The speech, entitled Against the Stepmother for Poisoning by Antiphon, clearly reveals that the Athenians practised and believed in love potions and may suggest that this more subtle form of erotic magic (compared to the casting of spells and the making of enchanted dolls) was the preserve of women.

Desire between women

Within the multiplicity of spells found in the Greek Magical Papyri, two deal specifically with female same sex desire. In one of these, a woman by the name of Herais attempts to magically entreat a woman by the name of Serapis. In this spell, dated to the second century AD, the gods Anubis and Hermes are called upon to bring Serapis to Herais and to bind Serapis to her.

In the second spell, dated to the third or fourth century AD, a woman called Sophia seeks out a woman by the name of Gorgonia. This spell, written on a lead tablet, is aggressive in tone; for example:

Burn, set on fire, inflame her soul, heart, liver, spirit, with love for Sophia …

Gods and goddesses were regularly summoned in magic. In the spell to attract Serapis, for example, Anubis is included based on his role as the god of the secrets of Egyptian magic. Hermes, a Greek god, was often included because as a messenger god, he was a useful choice in spells that sought contact with someone.

The tendency to combine gods from several cultures was not uncommon in ancient magic, indicative of its eclectic nature and perhaps a form of hedging one’s bets (if one religion’s god won’t listen, one from another belief system may).

Deities with erotic connections were also inscribed on gems to induce attraction. The Greek god of eroticism, Eros was a popular figure to depict on a gemstone, which could then be fashioned into a piece of jewellery.

The numerous erotic spells in antiquity – from potions to dolls to enchanted gems and rituals – not only provide information about magic in the ancient Mediterranean world, but the intricacies and cultural conventions around sexuality and gender.

The rigid system of clearly demarcated gender roles of active (male) and passive (female) partners, based on a patriarchy that championed dominance and success at all costs, underpinned the same societies’ magical practices. Yet it is important to note that even in magic featuring people of the same sex, aggressive language is employed because of the conventions that underlined ancient spells.

Still magic remains, in part, a mystery when it comes to erotic practice and conventions. The two same-sex spells from the Greek Magical Papyri, for example, attest to the reality of erotic desire among ancient women, but do not shed light on whether this type of sexuality was condoned in Roman Egypt. Perhaps such desires were not socially approved; hence the recourse to magic. Perhaps the desires of Sarapammon for Ptolemais were also outside the bounds of acceptability, which led him to the surreptitious and desperate world of magic.