MEDICAL HISTORIES - The second instalment in our short series examines how the spermatorrhoea epidemic changed the scope of medicine.

Every period arguably invents its own illnesses, medical disorders with symptoms that reflect the particular circumstances and anxieties of the time. The spermatorrhoea epidemic of the mid-to-late 1800s, like the much better known epidemic of female hysteria of the same time, is one such disorder that left a lasting legacy.

In contrast to hysteria, which has been the subject of analysis by medical historians and feminist scholars alike, spermatorrhoea occupies a very obscure position both within the history of medicine and of masculinities.

But for Victorian physicians like Albert Hayes, director of the Boston Peabody Medical Institute, and author of The science of life: or, Self-Preservation. A medical treatise on nervous and physical debility, spermatorrhoea, impotence and sterility, with practical observations on the treatment of diseases of the generative organs, (1868) the disease was amongst “the most dire, excruciating and deadly maladies to which the human frame is subject.”

The term spermatorrhoea, or spermatorrhée, was coined in 1836 in the first volume of the French physician Claude François Lallemand’s Des pertes séminales involontaires (1836-42), where it was used to refer to “an excessive and involuntary discharge of semen”.

Considered a form of sexual dysfunction or venereal disease, spermatorrhoea was associated with an oozy and incontinent seminal leakage. And because semen was identified as the source of men’s “vital heat,” the disease was thought to produce a whole series of debilitating bodily effects.

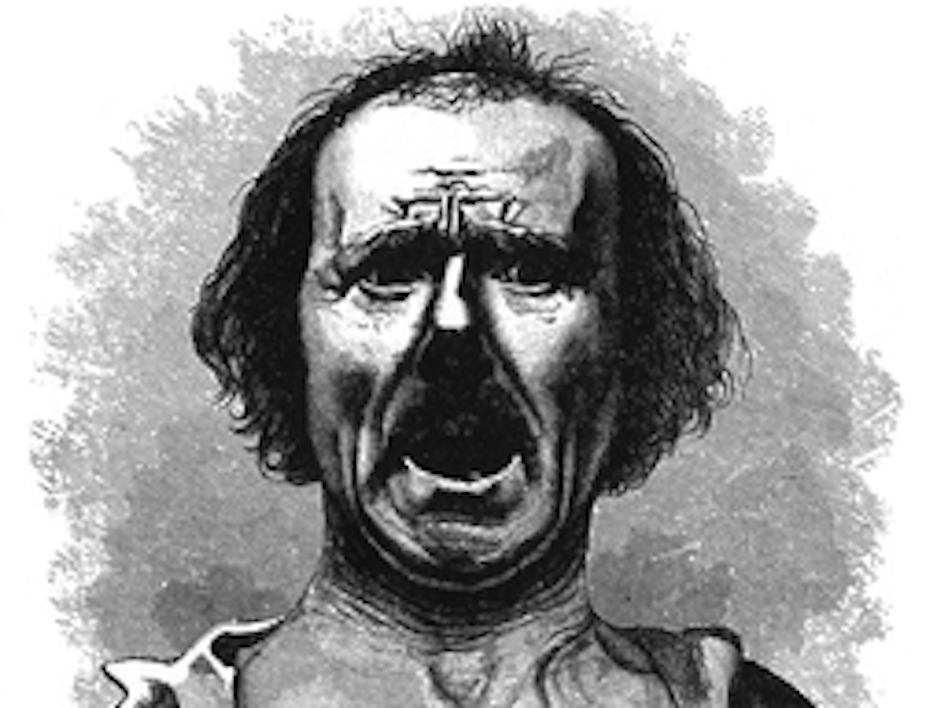

As physician John Skelton wrote in A Treatise on the Venereal Disease and Spermatorrhoea (1857), sufferers

of spermatorrhoea become fretful and peevish; their memory fails; they lose their courage, and indignities, which they would formerly have resented, they now endure with patience. They become confirmed hypochondriacs; are unfit for either business or serious reflection, and are disagreeable to themselves and the whole world.

Causes and consequences

Causes of the disorder were thought to vary widely, but were generally attributed to an overly-domesticated and unmanly lifestyle – feather beds, soft trousers, excess reading of sentimental literature, and sedentary pursuits were all cited as possible causes. But most physicians agreed with Robert Bartholow (Spermatorrhoea: Its Causes, Symptoms, Results and Treatment, 1879) that “the vice of masturbation is undoubtedly the chief cause.”

Spermatorrhoea rendered public and shameful men’s private loss of self-control, and his inability to live up to the expectations of dominant nineteenth-century masculinity. It provided a new diagnostic category in which nineteenth-century concerns about masculinity, virility and self-control could be read in the sexual anatomy of the male body.

Treatments for spermatorrhoea followed one of two approaches. The first was to focus on improving the general health and vigour of the body. In Practical remarks on the treatment of spermatorrhoea and some forms of impotence (1854), John Milton suggested, “Few means of controlling spermatorrhoea could be devised so simple and natural as exercise, especially gymnastics.”

The patient was encouraged to participate in his own treatment and might

do half the surgeon’s work if he will rise at five or six o’clock, sponge with cold salt water, use the dumb bells for half an hour, and follow this up with a brisk walk. It will not be long before the eye grows brighter, and the skin clearer; before he sleeps sounder and again feels comfort in existence.

If self-discipline failed, however, medical intervention was deemed necessary, and its severity demonstrates how dangerous spermatorrhoea was seen to be. Treatments included acupuncture of prostate and testes, blistering of the penis, and forced dilation of the anus.

“I have had excellent results from stretching the sphincter ani,” Bartholow wrote. “The operation causes considerable pain, and may rupture the sphincter if incautiously carried too far … but it has seemed the most useful in the cases of simple spermatorroea.”

The brutality of these treatments attests to a strong determination to discipline the male body, in order to prevent its dissolution into a pathological ooziness.

Structural change

The consequences of the spermatorrhoea epidemic were profound and led to an institutional shift in the structure and practice of medicine. It was as a direct result of this epidemic that professional medical practice was extended to include the treatment of sexual diseases and genitor-urinary specialisations for the first time.

As Angus McLaren notes in Impotence: A Cultural History (2007), urology was for a long time “tainted by its association with venereal disease and impotence,” and doctors “who discussed such issues were acutely aware of their apparent unseemliness.”

There’s a concentrated effort to challenge this in the spermatorrhoea literature and to make the treatment of sexual disorders a part of the practice of mainstream medicine. Dr Pickford was one of dozens of physicians who protested that, “It is … this inexcusable neglect in medical men, which drive[s] the [sufferer] into the hands of nostrum-vendors and infamous quacks.” (1854)

An editorial in an 1857 edition of The Lancet exhorted, “Let honourable and scientific men take possession of the field now occupied by these vagabonds.”

It should be noted that this self-representation of the medical profession reluctantly turning to the neglected and distasteful disease of spermatorrhoea in order to save suffering men from the dangerous ministrations of quacks is primarily a rhetorical strategy – mainstream doctors and quacks offered similar, sometimes identical, treatments.

But the rhetoric was mobilised in the interest of affecting structural change, strengthening the professionalisation of this area of medical practice by prompting legal action to formally exclude and delegitimise the practice of quacks and restructuring general medical practice to include the treatment of sexual diseases, disorders and dysfunctions for the first time.

By the early 1860s, a spate of texts on “true and false spermatorrhoea” began to emerge. “False spermatorrhoea” was identified as being diagnosed by quacks, and “true spermatorrhoea” was redefined as a much rarer condition only a licensed physician could detect. This signalled the beginning of a rapid decline in spermatorrhoea diagnoses, and within a few short years, this epidemic had died away as quickly as it flared up.

Having transformed what had previously been known as “secret diseases” into something understood under the rubric of “sexual health,” and produced a series of corollary structural changes in the profession and practice of medicine, spermatorrhoea appears to have served its cultural purpose. Although it’s now an obscure footnote in the history of medicine, spermatorrhoea’s significance and effects remain important.

This is part two of Medical Histories – click on the links below to read the other articles:

Part One: Hypochondriac disease – in the mind, the guts, or the soul?

Part Three: Culture and psychiatry: an outline for a neglected history