Elephants in the room, part two

For all our schemes and mantras about making our lives environmentally “sustainable”, humanity’s assault on the planet not only continues but expands.

What are the deep problems that we don’t talk about in terms of our relationship with nature? What, so to speak, are the elephants in the room? This is part two of a series written by Professor Cliff Hooker, looking at some of these elephants. It follows his first instalment: population and the environment.

In this essay about curtailing our inharmonious swarming of the planet, Professor Hooker tracks a path from the often violent basics of population control, into an exploration of how stem cells offer a model for a new self-aware civilisation, right through to a posing a stark political question: how can democracy cope with over-population if individually we will not impose the necessary limits that were once enforced by ritual and tradition?

A wider view of population regulation

Every human society that is in harmony with its local environment will need to keep its population size constant.

Since all humans die after a finite time, they have to reproduce to stop the population number from falling. Since they suffer premature death from diseases, natural hazards (famine, predation and so on) and accidents, they have the capacity to reproduce at rates higher than replacement. But the reproduction has also to be constrained to stop the population number from rising.

If the population is not constant there are just two ways, overall, in which it can be stabilised: reduce the fertilisation rate, or increase the death rate. Suitable mixes of these options will also do, and our attention goes immediately to women and the pill, but (as we shall see) this is a narrow view.

Women: Females usually have only one or two children at a time and take at least nine months to do it (longer, including time for physical recovery and child-raising), while males can in principle inseminate many females, and do so frequently.

So women form a limiting factor in determining the reproduction rate, and many cultures have focused on reproductive control of women. But it does not follow that this is the only effective approach and in fact many of our options involve males - from abstinence through to sterilisation.

Pills: Western society tends to be so concerned with the sex act - fertilisation - that we tend to concentrate just on birth control and contraceptives when we think of regulating reproduction. In fact there are many other ways to do it, for example, through marriage rules or sterilisation, not to mention infanticide, which is a form of death regulation. And humans have tried them all. So let us take a broad look at the biological options for reproduction regulation.

(It might also be noted that control of females has often been primarily for purposes of dominating genetic inheritance and for social prestige. Both purposes are common in traditional patriarchal cultures and neither is concerned with creating harmony with the environment; in fact, they often worked to the opposite effect. Nor can we say that a patriarchy that regulates female reproduction is the “natural” condition for resource-poor people and cultures. Before sedentary agriculture set us on the path to increasing urban conglomerations and growth in resources, many cultures were evidently matriarchal, or at least they worshipped goddesses.)

Population regulation options classified

Given our biology, reproduction regulation is effectively the regulated production of fertilised females. And given the human capacity to over-produce, increases of fertilised females are achieved simply by relaxing whatever population reduction methods are in place. So this discussion will focus on the options for reducing the prevalence of fertilised females. We can intervene to achieve this at any point from conception of a new female through to her maturation to fertility, and we can prevent fertilisation either while leaving her alive or by causing her death.

One way to think through the possibilities is to ask, firstly, where they fall on the passive-to-active continuum. For example, the contraceptive pill, whether taken “before” or “after”, is an active intervention. On the other hand, adding the pill’s hormones to drinking water provides a passive intervention with no individual action required.

Secondly, we can ask where the actions fall on the individually-mediated-to-socially-mediated continuum; for example, taking the pill is first a specific action by an individual, while placing hormones in the drinking water is first a social action. Sterilisation, condom and intra-uterine device use, the rhythm method, withdrawal before ejaculation, and abstinence are all active, primarily individual interventions with varying degrees of social mediation. Dosing drinking water with hormones forms a passive socially-mediated intervention, while paying for a ticket in a reproduction lottery to chemically annul that hormone intake forms an active socially-mediated intervention.

Thirdly, we fix on a particular would-be female and ask where an intervention falls on her conception-to-fertilisation continuum. The pill is a pre-conception intervention, blocking her birth; sterilising her is a post-conception fertilisation prevention; killing her (abortion, infanticide) is a post-conception elimination (death) intervention.

Within this three dimensional framework (active-passive x individual-social x conception-fertilisation) we can locate any possible procreation intervention. For example, famine and increasing social stress (e.g. from work demands) - both of which can reduce fertility - thus act as passive, individually, respectively socially, mediated, post-conception fertilisation prevention measures. Gender-role selection (such as sending young women to monasteries) and tying burdens to potential brides (for example, through dowries) are active, socially mediated, post-conception fertilisation-prevention measures.

Here also we might place restrictive childbearing rules, such as China’s one-child incentives, while noting that the practical realization of prevention is through using one or more of the kind of interventions canvassed above. Abandonment of the aged (which outsources the killing to nature), or their euthanizing (which keeps the killing “in-house”), are active, socially mediated, post-conception elimination measures that do not reduce the number of available fertile females, but still cut the total environmental impact of a population.

Each of the mentioned measures, and more (the reader is invited to explore the 3D intervention space), has been used at one time or another by various societies. The measures are often practised in defiance of explicit cultural, mainly religious, rules to the contrary (for example in modern Catholic Italy and France). Measures differ in efficacy and risk and in the cultural and personal resources required to use them. Thus combinations of measures often work better overall than do options taken in isolation. For example, different couples favour different contraceptive practices (e.g. condoms versus withdrawal) so a mix is more effective than one alone, and it is more effective to back up reliance on large dowries (as is happening in India) with freely available contraception while the young save up.

These measures all intersect with, and often directly clash with, cultural lifestyles, and thus raise many sensitive ethical, religious, and cultural issues. As practically necessary as it might be in some circumstances, infanticide is typically at odds with religious injunctions against taking life. Even today in our own culture, let alone in more male-centred ones, males hesitate to undergo a vasectomy as a birth-control measure because they fear it will diminish their culturally specified manliness. And as already noted, European Catholic countries have long had low birth rates without evidence of persistent abstinence, despite the Church’s inveighing against contraception. And so on.

However, population regulation is not the primary concern of the religious impulse itself, and religious doctrine often has conflicted views about acceptable and unacceptable methods of internal self-regulation (many versions of Christianity once taught that masturbation is sinful while cold baths and withdrawal were not) and even between internal self-regulation and outsourcing it to external means (nature, god, or the rhythm method). A sustainable culture will need to adopt a mix of measures that are consistent with and supports its social tenets and practices; practically accessible and affordable; and efficacious in stabilising population.

From humans to all organisms

Before further considering human population regulation, I first want to expand the scope of the perspective. Every population, from amoebae to whales, has the basic problem of environmental sustainability, so every population has to practice some variant of these measures. The more primitive the organisms involved, generally the simpler are the accessible, affordable measures. Most animal populations are held stable through four great passive, individual, post-conception elimination measures:

Disease

Predation

Starvation

Accidents (e.g. fire, flood).

These forces held vast power over perhaps all humans in past times, and more than a few today. Due to forces beyond their control, early populations largely “outsourced” their population regulation to the environment, which it performed, with brute indifference, in these four simple ways.

In the animal world, there are some exceptions to the simpleness of regulatory measures. Kangaroos and timber wolves, for example, can modify their birth rates to suit estimated future feed conditions: kangaroos by delaying foetal maturation, wolves by modifying litter size. Now there is useful sophistication! Imagine if humans could modify their reproductive rate in the light of predicted conditions. In fact, we can, and do, most famously in the “demographic transition”, of which more below.

Cells, the simplest organisms.

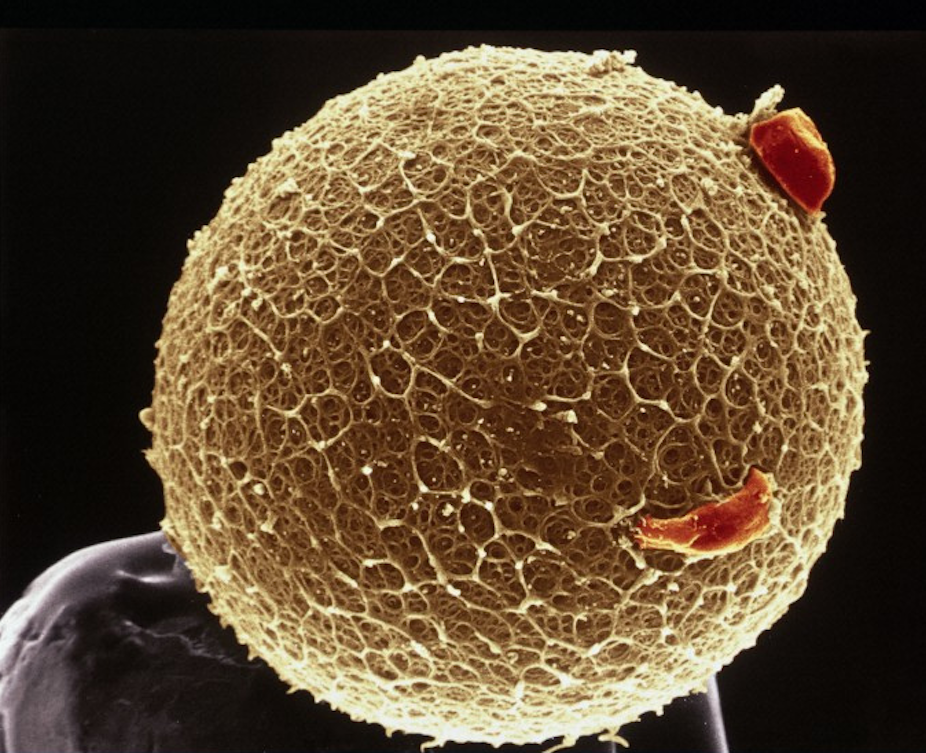

The need to regulate conception/development and death-rates reaches all the way down to the simplest possible organisms: single cells. If the cells form a population of separate individuals then they are subject to the same four elimination measures as other natural populations. But cells may also band together to form many kinds of colonies, including multi-cellular organisms like you and me. The cells in organismic colonies must cooperate so that together they deliver all of each organism’s functions, from digestion to running to speaking. To do this, individual cells are specialised for contributing to just one or a few functions, e.g. lung, muscle, and brain cells.

Thus the biggest constraint on these cells is their collective need to preserve all of their collective functioning all the time. In these circumstances it is crucial to keep replacing defunct cells, and to eliminate and replace malfunctioning cells, without over-producing cells. Cell conception is regulated in the bone marrow. Cell death can be natural (ageing), by specialist immune-system assassins (for malfunctioning cells), or “programmed”, that is, instructed by other cells when needed (apoptosis).

There is an additional problem: besides arriving in the right place at the right time, each new cell must also be specialised for its role there. Specialisation can’t be genetically determined in advance because no organism can tell just what specialisations, in what quantities, may be needed (e.g. to cope with shifting from a cold to a hot climate). It is instead much more efficient, and more adaptable, to construct pluri-potential or “stem” cells capable of communicating with the already specialised cells at its destined location, and turning into any specialised kind. For instance, our immune system doesn’t try to second-guess the pathogens with which we will come in contact, it learns how to destroy them once they arrive.

In sum, without harmony among these three processes - conception, specialisation, and death - the vast colony of cells that is a multi-cellular organism would quickly break down. Cancers flout each of these three regulations: they multiply limitlessly, won’t specialise appropriately, and trick immune system assassins into ignoring them while also ignoring signals to die. That is what makes cancers unique as multi-cellular system disturbances, and so damaging, and it is an important part of why they can be difficult to deal with medically. Humans have been described as a plague, but a Gaia enthusiast might insist we are more like a cancer.

On the other hand, the presence of the stem-cell specialisation system provides our medicine with a much more powerful way to intervene to deal with injury and disease, the fruits of which are only now beginning to appear. It may also see the emergence of inherent limits to multi-cellular organisation, e.g. ones that mean that cancer can only be defeated, not extinguished.

Humans face the same constraints as cells

Beyond multi-cellular colonies, these ideas generalise to any collection of adaptable, transitory and reproducing entities that collectively create between them stable functions persisting longer than their lifetimes, be they colonies (like ant nests), organisms or robots. In each case, to succeed they will either have to adopt some form of self-regulating control of conception, specialisation, and death, as cells do, or allow their environment to take over these same processes - generally a more brutal alternative.

Human colonies (aka societies) face these same constraints. Regulation of conception and death we have already reviewed, while specialisation takes the form of cultural conditioning and transmission through communication with others (e.g. education), much as it does with cells. The process is as important to human societies as it is to cellular societies; get it wrong and economic, social, and cultural imbalances and malfunctions quickly appear, and various forms of fertilisation and death self-regulation may fail or be changed. For instance, for several reasons people trapped in poverty in wealthy societies often revert to larger and/or more frequent families and find it difficult to adopt skills and habits that make for increased income, thus posing financial, educational, housing, and other social strains.

Grim environmental regulation by death

The nasty fates of various human populations remind us just how tightly outsourcing population regulation to the environment can bind because they emphasise death’s external regulation of reproduction. Historically, group after group degraded their ecological capital by consuming it to expand their populations until they collapsed in starvation, disease and accidents. See, for example, Jared Diamond’s Collapse and Guns, Germs and Steel for review and analysis. For instance, as a rough (not universal) rule, today’s hot deserts are as large and denuded as they are because earlier, collapsed “civilisations” degraded them.

Environmentally-regulated death also characterises earlier hunter/gatherer societies, despite their generally lower environmental impacts, through predation (lions, etc.), drought/flood, and accidents (from falls to earthquakes), but especially the toll of disease. The unfortunate but understandable outcome is large families so that enough children might survive to take over and take care, leaving a population over-reproducing but controlled externally by death. This is like a car with the accelerator and brake both on hard - and just as unstable and destructive if only one is eased even for a short time. Which tells us that the demographic transition to a wealthy modern society is not simple: to get it started requires altering the whole societal system of securities and incentives - including shifting from outsourced to internal population self-regulation.

Of course, relying mainly on death regulation remains nasty even when it is done internally. Jared Diamond also describes the harsh death regulation practices under which Tikopian people lived and died, and Tim Flannery (The Future Eaters) describes the descent of peaceful Maori islander culture into trench warfare following elimination of larger kiwis, their main food source. But before we criticise them let us acknowledge that through the draconian self-regulation of death in these ways (backed by some regulation of conception) they have survived for many centuries (Maories), and even millenia (Tikopians) and did so while largely isolated on islands with very limited food resources, which is more than many sometime “higher” civilisations have done.

It is no wonder then that, where feasible, regulation of conception or of post-conception fertilisation have always been the preferred approaches. They are inherently internal self-regulations.

The grand shift to self-regulation

It is striking enough that as we humans become wealthier and more complexly specialised, we increasingly replace regulation outsourced to the environment with self-regulation of population, and we shift from death as regulation (post-conception elimination) to the regulation of fertilisation, either by preventing conception or terminating pregnancy.

This is part of us humans taking into ourselves - individually and socially - control of our world to the extent that we find it possible and morally tolerable. This is a grand tale in its own right, encompassing agriculture and settlement, religion, culture, science and technology, and all to express the self-regulating autonomy we share with all life. (Is it any wonder then that it is also resisted by other organisms? Here are more elephants in the room.)

Still more striking, and on the current cutting edge of the grand tale, is that we achieve that regulatory shift inwards and conception-wards via our vastly more intense regulation of specialisation, while at the same time using that specialisation to relax self-regulation from the “hard” regulation of rigid societal rules to the “soft” regulation of individual and family judgement.

Twenty millenia and more ago, human life was dominated by outsourced environmental death-regulation. One millenium ago conception, social roles (specialisations), and deaths were all heavily regulated, externally and/or internally by strong collective religious cultures. Today, Western democracies have removed rigid societal collective regulation of conception, social roles, and death, replacing them with more powerful contraception regulation technology and more powerful education for specialisation, and a huge range of economic and social incentives, all responded to at the choice of the individual. This inevitably frees up a greater range of individual conception decisions, expressed in the rising numbers of single mothers, gay and lesbian couples, and the like, having or adopting babies, the increasing rate of in-vitro fertilisation babies, and in the increasing array of surrogacy arrangements that produce the babies.

Finally, Western democracies have in most countries already removed traditional forms of death regulation, dealing instead with the resulting “age explosion” through social support and, in what is in its early stages here but of widespread interest, and increasing in many other countries, through death by individual choice, that is, euthanasia. Voluntary euthanasia and assisted suicide are already legal in some form in the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxemburg, and Switzerland, and the US states of Oregon, Washington, and Montana.

We need an anthropology and philosophy of aging

The aged now make up an increasing proportion of the population, and aged-care activities and services make up an increasing proportion of the economy. At the same time Western culture has jettisoned the traditional role of the aged as respected elders dispensing wisdom. (Among other reasons this may be because rapid innovation renders the aged obsolete and technical creativity often peaks in youth.) And the West tends to avoid the public discussion of aging and death. (For a rare enough exception visit Virtual Hospice.) It is overdue for the West to begin a public conversation about the meaning of ageing, the social functions and value of the old, and how best to age and die. In short we need an anthropology and philosophy of aging.

Demographic transition = shift to internal self-regulation of life

The shift to internally-shaped internal (self) regulation of population is the true demographic transition. It is an intimate expression of the whole grand tale of humanity’s mounting self-regulation, our mounting autonomy. For this autonomy to reach its fullness, it is necessary to transform our economy and social structures in order to shift the basis of social and economic security from family and inherited access to land - applying to serf and lord alike - to social networks and saleable market skills, as has often been told (see, for example, Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation.

But equally necessary for societies if they are to fully realise population control that is soft and individually regulated, is to produce individuals with historically unprecedented capacities. Successful individuals now need, in a way that did not apply even two generations ago, a wide general knowledge of how their overall society works (e.g. how the labour market, labour laws, education and work experience system, taxation system and so on works). They must possess sufficient breadth of vision and life-planning skills to navigate a successful life-path for themselves and for their families and, as citizens, for their society. This includes sensible decisions about conception, specialisation and, increasingly, death.

There are three revealing indicators of the huge changes that have occurred in the last century:

1) Our children now have to cope with the unprecedented sweep of the internet-based digital media in addition to their family and school peer environments

2) Children are now under pressure to commit themselves to courses of education (e.g. mathematics versus arts) earlier and earlier in schooling and yet still often seem paralysed or frustrated at the enormous range of still-shadowy employment opportunities among which they still must choose

3) The time to establish increasingly complex career niches increasingly competes with optimal reproduction time.

The demographic transition is perhaps the most sensitive expression of what divides Western from many non-Western nations, e.g. expressed in the contemporary “clash of civilisations” (see the next elephant).

And within a democracy, when the demographic transition does not take hold in particular groups for cultural reasons so that they begin to out-breed the rest, the basic principle of democracy, one-person-one-vote, itself works to destabilise the society. Fiji and Sri Lanka are examples just in our neighbourhood (another elephant is glimpsed). How can the demographic transition be made more universal and robust, and thus into a stabilising force instead of being a de-stabilising force?

In addition, the West is also faced with huge challenges, including over its impacts on the environment, and its social re-organisation of family and social life (a future elephant in this series). So our self-regulatory reach must now be extended to the planet as a whole, and to the self in minute sub-cellular detail (e.g. through molecular medicine) - the great tasks for this century.

The question now becomes whether democracy can cope. Can a society open to self-determination for its citizens find a way to use its specialisation processes to deliver environmental and social harmony? Can it do this while preserving the increasing focus on individual choice, and while public life is increasingly dominated by fragmented market interests, including media interests, that are themselves expressions of individual choice?

What other soft internal regulation can we bring to bear in place of hard cultural controls to ensure some collective shape to our lives, including living healthily and harmoniously with our environment? Conversely, to what extent are we sinking into myopia, while literally growing like a cancer, and what new nasties may thereby arise that might surprise us to death?

These are the issues that underwrite fears that we have lost adequate leadership. Here too be elephants – watch this space.

Comments prompted by this story can be entered below the following sequence from the 1992 Godfrey Reggio film, Koyaanisqatsi: Life out of Balance.