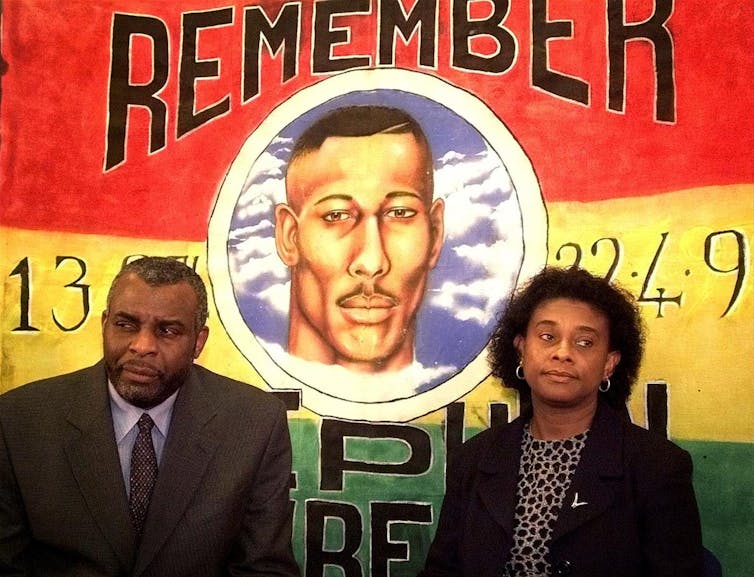

Almost three decades after the murder of Stephen Lawrence, ITV has launched a new three-part drama about Stephen’s parents, Doreen and Neville Lawrence. The series explores the Lawrences’ crusade to achieve justice for their son, a black British school student from Plumstead, south-east London, who was murdered in a racially motivated attack while waiting for a bus.

Stephen is a sequel to The Murder of Stephen Lawrence, a Bafta-winning 1999 film written and directed by Paul Greengrass, who has also been involved in the latest series. The new drama covers the events of 2006 – 13 years after the death of Stephen – and six years after a public inquiry found the London Metropolitan Police institutionally racist. It follows the efforts of Lawrence’s parents to bring their son’s killers to justice. It was their probing that eventually helped to secure the convictions of two of his murderers.

I was part of the Stephen Lawrence inquiry into police racism and his murder has had a lasting impact on me personally and on my research into police race relations. Now, 28 years after his death, I still feel close to him and the tragedy that hurt his family so deeply.

Police racism inquiry

When I was asked in 1998 by the Commission for Racial Equality, a public body in the UK that aimed to address racial discrimination, to write their evidence to the Stephen Lawrence inquiry, I had little idea that the case papers I read would be of such lasting importance.

The official papers certainly demonstrated that officers dealing with the case had been incompetent in the extreme. Central to their failures was, despite clear evidence to the contrary, an inability – deliberate or unwitting – to recognise that 18-year-old Stephen Lawrence was murdered for one reason alone: he was black.

This racial motivation was something the officers working on the case and, perhaps even more extraordinarily, senior officers who investigated subsequent complaints by his parents, refused to admit. It was and remains the concerted campaigning of Stephen’s parents that probed and to some extent revealed the truth of what happened when the Metropolitan Police investigated their son’s murder.

What has changed?

I have been researching police race relations for more than 30 years. As I write this article I know that hardly any forces have a distinct race policy. Instead, they have diversity and inclusion policies that include a watered-down idea of race as if it is the same as gender, sexuality and disability – and they pay far less attention to race than to sexuality and to gender.

The National Police Chiefs Council does not have a policy about racial prejudice and discrimination. Indeed, some police chiefs are reluctant to accept a national policy, preferring their own local approach. They worry about getting things wrong and being called “racists”.

In my experience, there is a real inability to understand the dynamics of race within policing, and many chief officers only have a passing interest in engaging with issues surrounding race. Very little has been done. Do not forget that as you watch Stephen. The legacy of his murder demands something far, far stronger.

For black British people, especially serving black police officers, the history of race discrimination within and outwith constabularies lives on. I call this the “institutional memory of race” and it brings the past into the present when officers encounter or hear about race prejudice or discrimination.

Every industrial tribunal – there have been many – when a black officer calls a chief to account; every report about racialised differences in discipline hearings; every resignation with discriminatory overtones. This is when the institutional memory of race is at play – and it is something that many white officers are unaware of.

Racial prejudice lives on

So for viewers watching the new ITV series, the events of 1993 and the racial prejudice and discrimination that led to Stephen Lawrence’s death may be seen as an event lodged and preserved in the past. But you only have to cast half an eye to Twitter and other social media sites to find overt racial prejudice.

Only a few months ago, England’s black football players representing their country in the recent Euro competition were targeted on social media with racial prejudice because they were black. And from 2019 to 2020, about three-quarters of all hate-crime offences were related to race. Police recorded 76,070 race-hate crimes in this period – a 6% increase on the previous year. And the real figure is likely to be much higher as many incidents go unreported.

This is why episodes of Stephen should be viewed not just as an important historical event. But rather a reminder that the overt race discrimination that led to his death has been perpetuated across the decades and still lives with us today.