More than 30 years after the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence, London’s Metropolitan Police have named a new suspect. A BBC investigation identified Matthew White as a sixth suspect, raising questions about why it took police two decades to properly investigate White, who died in 2021.

As Deputy Assistant Commissioner Matt Ward remarked, the police made numerous mistakes in their initial investigation of the attack. These mistakes have continued to resonate throughout discussions of racism (and police responses to it) in British society for the last three decades. This news comes just three years after the police officially marked the case as “inactive”, and at a time when trust in the police is low, particularly among people of colour.

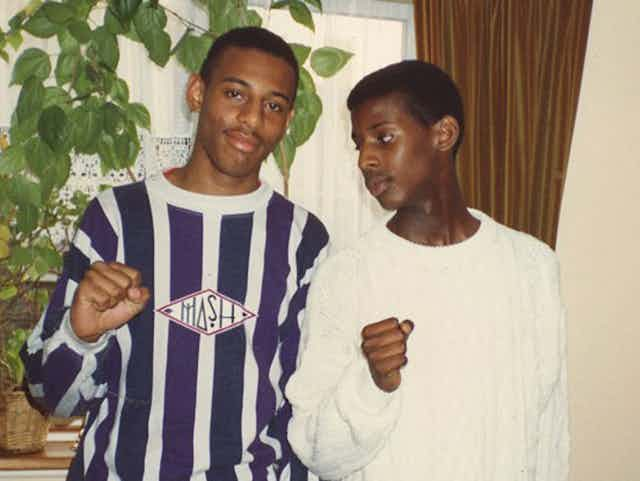

Here’s what was always known: on April 22 1993, 18-year-old Stephen Lawrence was stabbed to death while waiting for a bus in south-east London. Lawrence and his friend Duwayne Brooks were targeted in an unprovoked racist attack by a gang of white youths.

The Met’s investigation initially disregarded the clear racial aspect and instead profiled these two young black men as probably being involved with gangs. They racially stereotyped Brooks, treating him as a suspect, rather than a victim. He was characterised as displaying “unpleasant hostility and agitation” towards the police when, in reality, he was in shock and frustrated by a lack of action.

Lawrence’s family and their lawyer were also racially stereotyped by the police, distrusted and believed to be trying to “make trouble” for the authorities. Evidence later emerged suggesting that the police spied on the Lawrence family and attempted to tarnish their reputation, with the aim of discrediting their campaign highlighting police failings.

Arrests and acquittals

Almost immediately, police received information about Lawrence’s suspected killers. But it was two weeks before they made any arrests. During this time, police twice observed the suspects removing large rubbish bags from their homes, potentially destroying incriminating evidence.

Eventually, five white men were arrested on suspicion of the murder of Lawrence – although Brooks has always maintained there were six attackers. The charges against them were dropped, with the Crown Prosecution Service citing insufficient evidence.

The Lawrence family launched a private prosecution against three of these suspects in 1994. This too resulted in acquittals, due to similar conclusions of a lack of evidence.

It wasn’t until 2012, following new examination of forensic evidence and the government scrapping the double jeopardy legal principle, that Gary Dobson and David Norris were found guilty of Stephen’s murder. The other four main suspects – including the recently named Matthew White – have never been convicted for the crime.

For years, police considered White just a witness, having been in the area and interacted with some of the suspects on the night Stephen was murdered. Other evidence and witness statements suggesting White was himself involved in the attack were not properly investigated until decades later.

Macpherson inquiry

Following the persistent campaign by the Lawrence family and supporters, a public inquiry was launched in 1999. Sir William Macpherson, a retired high court judge, was tasked with examining the circumstances of Lawrence’s murder and the police’s ineffectual investigation.

The Macpherson report concluded that senior Met officials failed in their leadership, and outlined numerous examples of professional incompetence. Many previous recommendations, such as changes in training and the recruitment of more people of colour into the police force, were simply ignored.

Macpherson then made 70 recommendations, ultimately aiming for “the elimination of racist prejudice and disadvantage and the demonstration of fairness in all aspects of policing”. Of these, 67 were implemented in practice or law within two years.

Most notably, Macpherson labelled the Met “institutionally racist”, defining this as the organisation’s collective failure “to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture, or ethnic origin”. Macpherson’s understanding of institutional racism and its impact was influenced by the unrelenting campaign of Lawrence’s family and evidence presented by black people. As one activist declared: “We taught Macpherson and Macpherson taught the world.”

Impact felt today

Two decades later, Macpherson’s damning declaration of the Met as institutionally racist has had limited impact. More recent studies have found little actual evidence of changes in police culture.

The 2023 Baroness Casey review found that the force is still institutionally racist, as well as institutionally misogynistic and homophobic. Met Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley rejected the label.

Read more: Casey review: key steps the Met police must take to address its institutional racism and sexism

In 2020, the Met announced that the Stephen Lawrence murder investigation had become “inactive”, as there were no further lines of inquiry. The revelations about White have again prompted calls from the Lawrence family and campaigners to reopen the criminal investigation into the most notorious racist murder in modern British history.

Lawrence was an intelligent, popular, aspiring architect – a “shining example”, in the words of one newspaper. His family were also seen as dignified and principled in the face of such a tragedy. In looking back at how the case developed over the years, it is clear that these factors influenced the public to rally behind the campaign for justice.

Of course, it shouldn’t be necessary for the victim of a racist murder to be of “impeccable” character for the murder to outrage the public and be properly investigated. This case, and the response, forced the general public to acknowledge the reality of violent racism in modern Britain – something that people of colour had known for a long time.