Byelections are curious beasts in the political jungle. On the one hand, they are objectively minor political events: the replacement of a single MP for however long is left until the next general election. On the other, they become crucibles for bigger political debates; the national played out on a local stage.

So it was in Stoke Central in recent weeks. For the commentariat, here was the perfect counterpoint to the byelection in Richmond held in December. Richmond was a strongly pro-Remain constituency so when the Liberal Democrats won, a narrative could be built that their success reflected the divisions caused by the EU referendum. Stoke was an archetypal Leave constituency, the “Brexit capital of Britain”. As such, it was the ideal place for UKIP to shine and its new leader, Paul Nuttall, to be vindicated in his new strategy for the party.

The Stoke result, which saw the seat remain in Labour hands with a small swing away from UKIP, thus raises important questions for both Nuttall and those observing him. Is Stoke going to be UKIP’s graveyard?

First, let’s consider the big narrative that was applied to Stoke. Certainly, with nearly 70% of voters in the Leave camp last summer, the constituency looks to be the kind of place where UKIP could do well, given that it was the only national party to campaign wholeheartedly for exit from the European Union. Add in the generally high levels of dissatisfaction found in the town – as evidenced by low turnout in elections and the state of the local economy – and it is not hard to see why this feels like a classic “left-behind” part of the country, losing out on globalisation and modernisation.

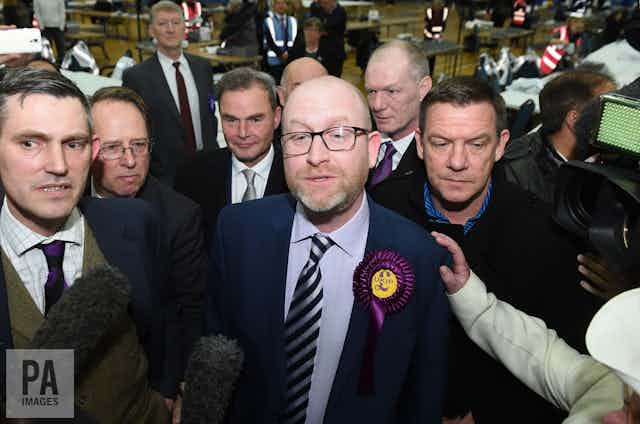

UKIP played up to this, especially in the national media and in its choice of the party leader as candidate. Paul Nuttall isn’t Nigel Farage, either in style or in substance: a firm exponent of “red UKIP”, he sees the future of the party in supplanting Labour, rather than the Tories, in the political landscape. At a time when Jeremy Corbyn appears to be alienating more Labour supporters than he is winning over, this has looked like the most viable strategy for a party that needs to reinvent itself after securing its headline goal.

Beyond Brexit

And yet, as so often with big narratives, there are gaps and misinterpretations. The most obvious is that Stoke was not contested over Brexit in the way that Richmond was. Indeed, neither Labour nor UKIP made much of the issue in their campaign literature or public statements, mainly because it wasn’t a topic on the doorstep. Instead, the debate was about public services and economic regeneration: Brexit was a given, by and large.

Equally obviously, the personalities of the two main candidates loomed very large in this byelection. Both Nuttall and his Labour opponent, Gareth Snell, were subject to intense media scrutiny over past actions and words, with neither emerging unsullied. In particular, Nuttall was marked out for his very limited connection with the constituency and his confused involvement with the Hillsborough disaster. Where Farage might have been able to shrug off such points, Nuttall has much more limited political experience and little political capital to use.

Put differently, Nuttall was the wrong candidate for the seat. In UKIP’s long history, it has almost always struggled to address this problem. Indeed, it is worth noting that the only successful byelections came from two Tory defectors – Douglas Carswell and Mark Reckless – each with relatively strong local profiles and track records, as well as a more loose association with the party. Parachuting in an outsider might make sense for a party trying to get its bigger names into elected offices, but it plays badly on the ground.

Where now?

Stoke Central looks very much like a missed opportunity for UKIP. Success here would have opened up a very much more credible line of attack for the party, especially since it would have made Corbyn’s position as Labour leader even more problematic. Even the poor turnout caused by Storm Doris should have played into the party’s hands, as more indifferent, moderate voters stayed at home. If the 2015 general election established a long list of second positions in constituencies for UKIP, then Stoke should have been an excellent opportunity to start converting these into first places.

But, then again, UKIP is nothing if not resilient. In the grand scheme of things, this defeat ranks well behind past failures. However, the big unanswered question is how the party responds now. Nuttall has indicated that he will remain as leader – albeit with the unfortunate phrasing “I’m not going anywhere” – but as the past year has shown, the party is not above edging out its leaders. In addition, there remains the Farage wildcard: talk abounds of him moving to form a new movement with UKIP’s erstwhile backer Arron Banks that could drain much of UKIP’s support base.

Stoke is thus not the end of UKIP, but it has thrown into stark relief the difficult position the party finds itself in.