Climate policy is back on the agenda in Canberra this week, with the focus on the government’s centrepiece Direct Action plan. The Coalition will have to negotiate with the Palmer United Party, which will reportedly not support Direct Action unless legislation for the idea of a “dormant” emissions trading scheme, with an interim price of zero, is also passed.

Currently, Australia has no overarching policy to reduce carbon emissions, following the repeal of the carbon price in July.

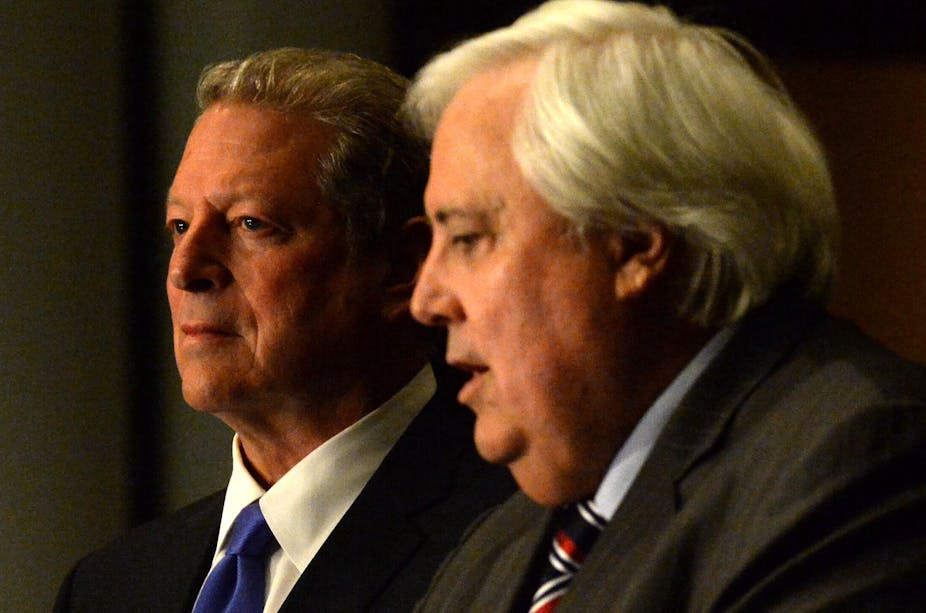

Palmer announced the scheme at a joint media conference with former US vice president Al Gore in June. The emissions trading scheme would have no price until key trading partners — China, India, Japan, South Korea, the EU, and the US — also develop national emissions trading schemes.

Meanwhile, new modelling from RepuTex has found, once again, that without amendment Direct Action will fail to achieve Australia’s legislated emissions target of 5% below 2000 levels by 2020.

So, what might Australia’s climate policy end up looking like, and could Palmer’s emissions trading scheme – even with a zero initial price on emissions – act as a stopgap?

Climate and energy go hand-in-hand

We need to deal with climate change because of impacts on food, water, ecosystems, health, extreme events and sea level rise. We will see direct implications for Australia, and indirect effects through migration, trade, technologies and capital across borders.

We also need a secure energy supply for Australia, capable of riding the changes and shocks generated by these same global flows. Given that current climate change is driven by greenhouse gas emissions, and the majority of greenhouse gas emissions are driven by energy generation, these two great drivers go hand-in-hand.

But after more than a decade of often factious debate, almost nothing is clear about Australia’s long-term strategy to deal with these issues.

The atmosphere of confusion is enhanced by recent politics: a bad outcome for the economy because industry is unable to make crucial investment decisions in an uncertain policy environment.

This makes it even more important than usual to sort the signal from the noise.

One step forward, two steps back

Three broad policy tools can be used to drive emissions reductions and energy resilience: a price on carbon, incentives, and regulatory mechanisms. Australia needs a mix of all three if we are to successfully drive down emissions while maintaining energy security.

The vast majority of economists and international organisations (including the International Monetary Fund, the OECD and others) regard a price on carbon as the most efficient mechanism for reducing carbon emissions.

But there are also barriers to innovation — such as technological and institutional inertia — that we need to address. We can do this with the two broad policy tools that accompany a price on carbon: incentives, to encourage transformation, and regulation, for instance for energy efficiency in the domestic, industrial and transport sectors.

Over recent years, Australia has developed — and now largely discarded — several policy responses that draw from this broad toolkit. These include:

- A legislated price on carbon emissions, so that they can be economically valued;

- An Emissions Trading Scheme, to transmit the carbon price signal throughout the economy and maximise the efficiency of emissions reductions;

- A Renewable Energy Target to incentivise the uptake of solar, wind and other near-zero-emission renewable technologies in electric power generation;

- The Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) to provide seed funding for renewable energy projects, support research and development, and share knowledge, thus filling market gaps;

- The Clean Energy Finance Corporation to mobilise private capital investment in renewable energy, low-emission technology and energy efficiency;

- The Climate Change Authority to provide independent advice to Government about the scale of the emissions-reduction challenge for Australia.

Since the election of the Abbott government, all of these initiatives have been abandoned or are under threat.

The carbon tax and its associated emissions trading scheme have been axed, the Renewable Energy Target is under a review that has been signalled as likely to lead to a reduced target, and the government has indicated its intention to dismantle ARENA and the Climate Change Authority.

In this situation, some of the furniture may be saved by the unlikely intervention of Al Gore in influencing Clive Palmer’s approach to the issue. The Palmer United Party will support retaining the Renewable Energy Target, the Clean Energy Finance Corporation and the Climate Change Authority, along with an initially dormant, zero-price emissions trading scheme.

Starting at zero

At first sight, a zero-price emissions trading scheme looks like an empty gesture. Certainly, it is inferior to a genuine, consistently applied price on carbon, without exemptions, starting now.

But that option is politically unattainable at the moment, so we have to consider the next-best options.

Australia will inevitably need a trading scheme to respond to a rapidly changing world environment. Otherwise, carbon pricing could be used as a de facto trade barrier against Australian goods and services produced without a carbon price component, as other countries add their own carbon prices to Australian products.

In contrast to government claims, the world is not moving away from trading schemes (see here). Schemes already exist in the European Union, Switzerland, New Zealand, South Korea, Kazakhstan, Quebec and Alberta in Canada, some US states, and parts of Japan. Trading schemes are expanding rapidly in the United States, China, and elsewhere.

While far from ideal, an emissions trading scheme with a zero carbon price has four things to offer:

- It equips Australia to respond quickly to widespread international uptake of an emissions trading scheme.

- It provides some guidance for industry, which can plan for an eventual price on carbon while tracking current international pricing levels, knowing that an Australian trading scheme can (and likely will) be implemented fairly soon at short notice.

- It would build on trading scheme design work over the last few years, in government, industry and non-government organisations.

- These steps would drive behaviour change, even in advance of a price being implemented.

Although a zero-price emissions trading scheme looks empty at first, it is a stop-gap option that is much better than the no scheme at all.