The two pieces of Commonwealth legislation strictly regulate research use of human embryos in Australia are currently being reviewed. The Australian public is overwhelmingly in favour of stem cell research despite the objections of a vocal minority, based on their perception that the destruction of embryos equates to destruction of life.

Australian scientists have been permitted to use donated in vitro fertilisation (IVF) embryos for a range of research applications since the laws’ introduction in 2002.

Such research might include techniques for improving treatment for infertility, genetic testing for serious diseases, or derivation of new human embryonic stem (ES) cell lines to better understand how to grow cells the body can use to repair itself following injury or disease.

The review of Research Involving Human Embryos Act 2002 and Prohibition of Human Cloning for Reproduction Act 2002 is required by the legislation. It is being done by an independent committee led by a former judge, the Honourable Peter Heerey QC.

It provides a welcome opportunity to reflect on whether current laws are keeping pace with both scientific and community standards and needs.

This is not the first review of the legislation – there was a previous one in 2005 which resulted in amendments allowing somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), which is also known as therapeutic cloning.

The 2005 legislative change made Australia one of the most progressive countries in the world for stem cell research.

The current review

In January this year, the Review Committee made a call for written submissions from the public, scientists and representative organisations.

To date, a total of 167 public submissions have been lodged on the Review website.

The majority of these submissions were from lay individuals or made on behalf of organisations such as the Australian Christian Lobby, Australians for Ethical Stem Cell Research, Australian Family Association and the Coalition for the Defence of Human Life.

Not surprisingly, they called for the clock to be wound back.

These submissions would like to have research restricted or banned due to concerns about the morality or the belief that scientific developments make the creation of human embryos by SCNT obsolete.

The remaining submissions, mostly lodged by national and international scientific organisations on behalf of their constituents, or by patient support groups, were supportive of the current legislation.

These included submissions from the Australian Academy of Sciences, Australian Stem Cell Centre, Australian Medical Association, Coalition for the Advancement of Medical Research Australia and Fertility Society of Australia.

Interestingly, a minority of the supportive submissions, 13 in total, actually called for a relaxation in the current regulations around specific issues.

They call for research into mitochondrial disease; the use of animal eggs for SCNT research; and the need to consider more appropriate compensation for women who donate eggs for research purposes.

With this diversity of opinion and beliefs, the challenge for the Review Committee is to find the right balance between opposing voices.

This challenge, due in no small part to the complexity of stem cell science, is compounded by the rapid rate of developments in this field.

Stem cell research explained

To the uninitiated, even the term “stem cell” can be confusing.

What is the difference between adult stem cells, embryonic stem cells, or stem cells from cord blood, and what about induced pluripotent stem cells (often abbreviated to iPS cells) that have just been discovered?

Is one type of stem cell better than others for use in research or to treat patients?

To start with, it is worth remembering that stem cells have been used in research and in treatments for many years.

Adult blood-forming stem cells were first used when whole bone marrow transplants were trialled for leukaemia patients treated with irradiation and chemotherapy in the late 1950s.

Although these initial attempts were frequently unsuccessful, progress over recent decades means blood stem cell treatment is a cornerstone of therapy for cancers such as leukaemia.

Ongoing research has revealed that most, if not all, tissues contain stem cells, although often in very small numbers.

Researchers are moving quickly to harness the potential of these stem cells with methods being developed to generate other cell types such as skin, nerves, bone, cornea and cartilage.

However, adult stem cells do not hold all the answers to the regenerative medicine puzzle.

Many types of adult stem cells cannot be readily grown or expanded in the laboratory and adult stem cells can generally only develop into a limited set of tissues.

The discovery of human embryonic stem (ES) cells in 1998 further broadened the possibilities for regenerative medicine.

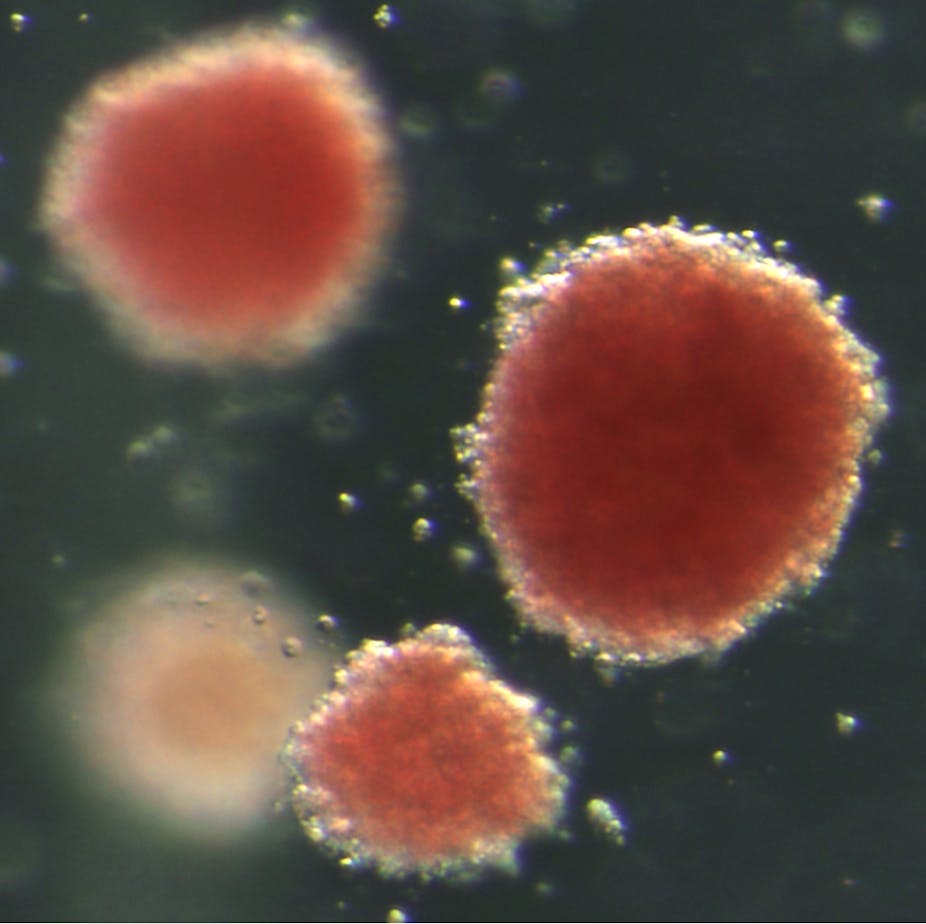

These stem cells, grown in the laboratory from donated IVF embryos no longer required for infertility treatment, can be coaxed by researchers to grow into many different types of cells.

This allows the processes of development to be studied in the laboratory and ultimately, the potential to develop new treatments to replace diseased or damaged cells in a large range of medical conditions.

Indeed, based on experiments performed over the past 30 years with mouse ES cells, scientists believe that human ES cells have the potential to make all of the over 200 cell types in the human body.

It should also be remembered that ES cell lines are effectively immortal. This means the same lines can be used to derive new knowledge in many laboratories around the world for many years.

With the advent of somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), it was hoped that such pluripotent stem cells - cells that have the potential to differentiate into almost any cell in the body - could also be made from a patient’s own cells to study a particular disease.

They could also be used to generate cells that are a genetic match to the patient, thus removing the prospect of rejection upon organ transplantation.

Right from the start, ES cell research was opposed by some members of the community as it necessitated the destruction of a human embryo. They see this as the loss of a potential human life.

Australian legislation allows research (such as the making of new ES cell lines) using human embryos but only following a formal licensing process.

The legislation requires scientists to justify why they need to use embryos and show the steps they have taken to ensure donors fully understood the proposed research and its implications.

However, recent developments have again challenged for some whether ongoing use of human embryos for stem cell research is justified.

In 2006, scientists showed that cells with very similar properties to ES cells could be made by “reprogramming” skin cells.

This needed the introduction of extra copies of just four genes, a feat not thought possible only a few years earlier.

These reprogrammed cells - induced pluripotent stem cell (iPS cells) - have been hailed as an ethical alternative by many who oppose to human ES cell research.

However, many scientists are now urging caution against advocating human ES cell research being completely replaced by research using iPS cells.

There are significant issues concerning iPS cells relating to genetic stability, safety and their efficacy for generating the desired differentiated cells.

So at this stage, ES cells derived directly from human embryos remain pivotal in the quest to understand, assist and control how the body repairs itself following injury or disease.

Indeed, the first clinical trials using cells obtained from human ES cells to treat spinal cord injury and blindness have recently commenced.

Perceptions of stem cell research in Australia

There’s no question about the diversity of opinions in Australia in relation to the use of human embryos in research, particularly in stem cell research.

But the wider community’s perception of stem cell research is not as polarised as one might think.

Numerous surveys conducted between 2001 and 2010 by various groups, including Roy Morgan, the Government and Research Australia, have all put public support for the derivation and use of human ES cells within the vicinity of 70% or greater.

While a majority of the public submissions to the current Review call for the repeal or restriction of the legislation, this opposition is not an accurate reflection of the views of the Australian public.

It is too early to know which type of stem cells will prove to be the most useful for any given disease or condition. In fact, it is likely that different diseases will benefit from stem cell therapies from different sources.

What is certain is that ongoing research looking at the whole spectrum of stem cell types will be required to deliver safe and effective regenerative therapies for human disease and injury.

We now wait to see how the Review Committee will evaluate changes in the scientific landscape and the breadth of public opinion. Its findings are due in late May 2011.

Links to surveys

Research Australia - Health and Medical Public Opinion Poll 2006

Roy Morgan (2001) - Four-nation study finds support for controversial treatment