Adolescent boys who take stimulant medication to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) for more than three years are likely to be slimmer and shorter than their peers, a new study has found.

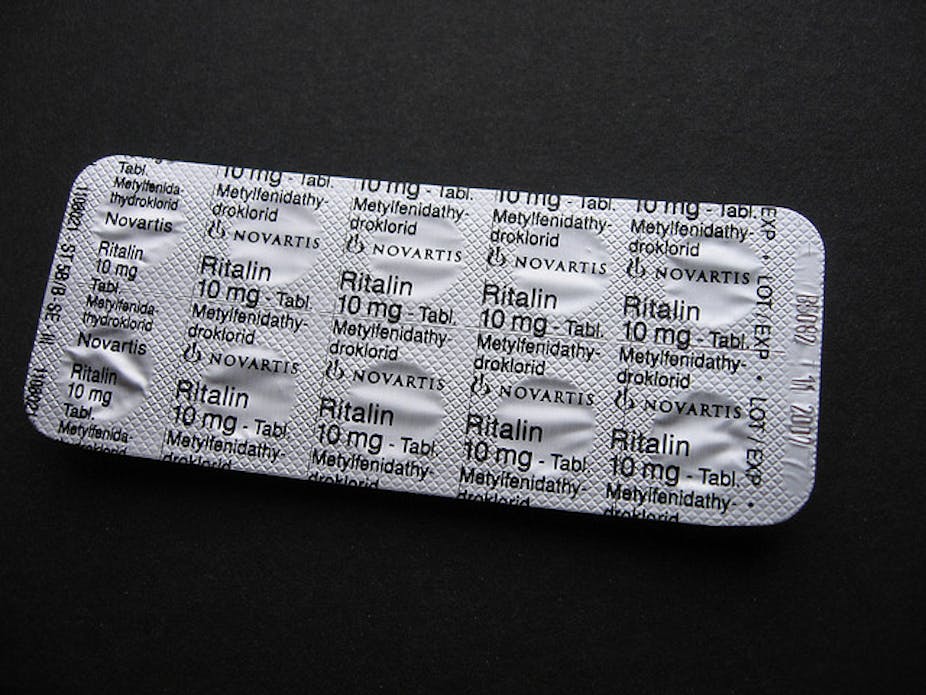

ADHD, characterised by a difficulty in staying focused and paying attention, is sometimes treated with drugs such as methylphenidate (Ritalin) or dexamphetamine, as well as behavioural programs.

The study, published today in the Medical Journal of Australia, examined data on 65 boys aged between 12 and 16 years who had ADHD and had been on stimulant medication for more than three years.

Boys aged between 12 and 14 years who took stimulant drugs for ADHD were lighter and slimmer than boys of the same age without ADHD.

Boys aged between 14 and 16 years with ADHD had lower weight but were also significantly shorter than the control group, the study found.

The researchers also found that taking ADHD stimulant medication could affect the rate that boys progress through puberty.

“For the younger children who were between ages 12 and 14, there wasn’t any discernible difference in the stage of puberty between them and the control group. But in the older boys, the 14 to 16-year-olds, the ones on ADHD medication were behind in their puberty,” said lead author, Dr Alison Poulton, clinical senior lecturer at Sydney Medical School Nepean, at the University of Sydney.

“That suggests that in early puberty the ADHD boys are entering puberty at the same age but it looks as though they may be progressing more slowly.”

Dr Poulton said that children who take ADHD stimulant medication can lose their appetite, which can slow down their growth.

“I think the important thing is no one should be treated unless they have got a significant problem. If the problem is bad enough, you consider all available treatments, including behavioural treatment and if necessary, medication,” she said.

“You weigh up the pros and cons of treating and of not treating. The effect on weight and growth in height needs to be taken into consideration.”

Dr Poulton said ceasing medication could allow boys to ‘catch up’ on their growth within a year to 18 months, but that it was important to remember that height and age of puberty varies greatly within families and among peers anyway.

Dr Brenton Prosser, a senior lecturer at the Australian National University’s School of Sociology and a researcher of the sociology of ADHD said that the notion that medication stunts growth is not new.

“But I agree with the authors, this is the first study that I am aware of that seeks to measure it, definitely in Australia,” said Dr Prosser, who was not involved in the study.

“The common wisdom is that medication inhibits appetite which restricts growth in height and weight over the longer term. Their finding that it delays puberty is a bit more bold and less convincing. How does one define, standardise and measure something that is so unique to the individual and subjective?”

“My position on all such studies is that individual development and medication are important matters to understand, but what turns these physical and behavioural characteristics into problems are the reactions of those around - that is, society.”

“We need to understand both sides of the coin, because only looking at one side produces a ‘medication is good or bad’ debate, which is ultimately unhelpful,” he said.