What would Christmas, or even the weeks or months leading up to it, be without lights? They make our trees twinkle, fill our windows with a welcoming glow and set our streets alight with Christmas spirit.

One city that takes its Christmas lights very seriously is London – a bright and eventful destination all year round, of course, but even more so in the build-up to Christmas. One after the other, streets and squares are illuminated by elaborate light installations, which transform urban spaces and alter the atmosphere of the city.

But as well as being a dazzling spectacle, the history of London’s Christmas displays can shed light on the shifting relationships between citizens, local councils and corporations in the city.

The tradition began in 1954, on Regent Street, when local retailers and businesses – through the Regent Street Association – arranged for a display. The aim was to show that post-war London did not have to look “drab” around Christmas. In the 1950s and 1960s, the installations spread to other streets, with the Oxford Street Christmas display premiering in 1959. Quickly, the lights grew to be a key part of London’s festive calendar.

By the early 1970s, however, economic pressures on retailers and local councils – combined with a darkening of public opinion – meant that London went largely without Christmas lights for several years. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the tradition returned once again, an initiative of local traders’ associations.

Celebrity sparkle

Today, in London’s famous West End, every street and square worth its name is lit up and presented as a sparkling centre of entertainment and – as ‘tis the gift giving season – commerce. A “dark” street during Christmas time signals to consumers that there is nothing going on, while lights guide the way, generating excitement and attracting attention.

To add to the glamour, lights are formally switched on each year by celebrities at crowded ceremonies. Big names in the past have included Kylie Minogue (Regent Street 1989 and Oxford Street 2015), the Spice Girls (Oxford Street 1996), and Helen Mirren (Bond Street 1998). Last year’s big names included Jennifer Saunders, Craig David and Holly Willoughby.

These “switch ons” are usually organised to create a buzz, bring people together and kick-start Christmas shopping. But they can also be used for other purposes. For example, in 2016, in central London’s Soho district, the Berwick Street switch on was used to raise public awareness about plans to privatise the Berwick Street Market. Joanna Lumley – who is actively engaged in the Save Soho campaign – did the honours.

Some of the city’s major cultural institutions get involved, too. The Sugar Plum Fairy – from the Royal Opera House’s feature, The Nutcracker – performed and participated in the switch on of the Covent Garden lights in 2016, reflecting the area’s close connection to the performing arts.

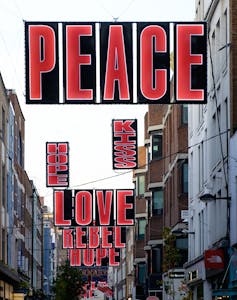

Over on Carnaby Street, the lights took inspiration from the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibition on the musical revolution and rebellion of the late 1960s. This ties in with the street’s past as a hotspot of “swinging London”.

So, these events present a fantastic opportunity to showcase the uniqueness of a particular area to Londoners and tourists alike – not least because images of Christmas lights always do well on social media.

Too tacky?

Yet these festive displays have not escaped criticism. For one thing, Christmas lights are expensive: many regional towns and cities have opted out due to budget constraints. There have also been some doubts as to whether they actually improve business. In 1993, the Oxford Street Traders Association decided not to provide a Christmas lights display: local retailers were reluctant to cover the costs, because they were not convinced that lights attract shoppers.

In the late 1990s, corporate sponsors tried a more direct approach, adding large brands, slogans and logos to the displays. This time, the public complained that the lights had become too commercial, unimaginative, “cheap” and “vulgar”, prompting the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) to invite architects to come up with new ways to improve London’s Christmas light displays, the best of which were exhibited at the Museum of London in 1997.

The RIBA campaign did not have an immediate effect: just one year later, Regent Street was given over to the soft drink Tango, which showered the area with bright orange bulbs and banners bearing the message “Tis the season to be Tango’d”. The display met with some considerable public scorn. Yet in 2016, it seems a different kind of branding is emerging: one which emphasises place, rather than product.

The Northbank Business Improvement District (BID) introduced Christmas lights to the Strand for the first time last year, emblazoning its name across the displays. This is part of a strategy to create a sense of place, which appeals to both visitors and investors – similar to what has been achieved on London’s South Bank. Whether or not the campaign will be enough to replace the area’s well-known moniker, “the Strand”, remains to be seen.

It may be that this whirlwind of shopping, tourism, atmosphere, business, branding, art, innovation, celebrities and photo ops has the power to bring us all closer together for a couple of months each year. At the very least, we can be certain that this year, Christmas in London’s West End will be anything but drab.