Voters across the UK will cast their ballots on July 4 to decide who will form the next government. Under the UK’s voting system, known as first past the post, voters choose one candidate standing in their constituency. Whoever wins the most votes out of those candidates becomes a Member of Parliament.

Although it is usually assumed that voters choose the candidate or policies that best reflect their values, this is changing.

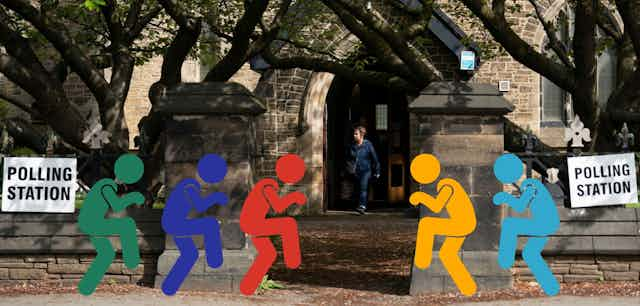

According to polling, 19% of voters at this election will be casting their ballots with the intention of keeping another party out, rather than voting their desired party in. These voters will opt for a “compromise” candidate – someone whose politics they may not share but is better placed to defeat their least preferred candidate.

The number of these voters has increased in recent elections. Between the 2017 and 2019 general elections, for example, the number of voters intending to vote tactically rose from one in five to one in four.

The influx of tactical voting websites, campaign groups, and their social media presence, has made this more of a possibility. Ahead of voters going to the polls this week, one centre left campaign group has created a voting hitlist of 451 constituencies where the Conservatives can be voted out. The aim is to encourage voters to cast their ballot in a way that delivers the heaviest possible election defeat to the Conservatives.

Although tactical voting disrupts our traditional understanding of how democracy is supposed to work, it is also a unique feature of the UK’s first past the post (FPTP) voting system.

FPTP is a “winner takes all” voting system. A candidate can win if they receive fewer votes than the sum total of all the other opponents. At the national level, parties have won majorities in parliament without winning a majority of votes.

Other countries, such as Germany operate voting systems that enable proportional representation and there are growing calls for reform in this direction in the UK.

Tactical voting is predominantly discussed on the left of British politics and in 2024, is aimed squarely at removing the Conservative government from power.

And while we can’t be sure how much of an effect tactical voting has on general elections, a series of byelections held since the 2019 general election have seen tactical voters come out in force. They’ve shown that if the tactical operation is well-organised and votes are distributed effectively, it can overcome the inherent distortions of FPTP, at least at the local level.

The Liberal Democrats saw remarkable gains in the Tory-held seats of North Shropshire, Tiverton and Honiton , and Somerton and Frome, while Labour’s vote share decreased. Conversely, where the Liberal Democrat vote declined in other constituency byelections throughout the parliament, Labour made gains in Wakefield, Selby and Ainsty, as well as recently in Blackpool South.

If the successes from these byelections is repeated in the general election, we could see tactical voting truly deliver some knockout blows for the Conservatives.

That said, Labour’s lead in the polls has left voters feeling confident that the Conservatives will lose anyway, so some may feel less urgency about voting tactically in 2024, especially as the campaign has worn on.

The optimum conditions for tactical voting at an election are when there is a single issue that becomes central to voters (like Brexit or Scottish independence), or when a tight competition between parties puts greater emphasis on the winner in each constituency.

At this election, though, Labour’s strong poll lead presents an obstacle to tactical voting. If voters think their local Labour candidate can beat the Conservative candidate, they will be less likely to vote tactically. With many feeling that Labour will form the next government, this phenomenon could be widespread across the UK.

Uniquely to British general elections, however, FPTP means there will be plenty of voters who wish they could just vote for what they want – rather than against what they don’t.