That he was singular – from the name onwards – and also a great parliamentary character are both true, but they do not get one very far in appreciating Tam Dalyell. They lend themselves to lampooning a person of profound seriousness, yet easily parodied.

It’s hard to situate him in a broader historical or political context. He was simply “Tam” – just as his most renowned intervention in the House of Commons, often after a flatulent or self-satisfied ministerial statement, was simply “Why?”

Few parliamentarians who came nowhere near holding office – Dalyell soared to shadow minister of science under Michael Foot in 1980 – have had such a profile. Bob Boothby comes to mind; and others such as Gerald Nabarro and Andrew Faulds, though they belong on the other side of that thin line separating character and caricature.

Man of principle

One can comfortably situate Dalyell in the Labour Party as both a Scot and a product of public school (Eton) and Oxbridge (Cambridge). But once again he was notable here: many leading Labour figures have been one, but few both. It somehow followed that Dalyell stood out, after his election in 1962, as an MP preoccupied with idiosyncratic causes.

In 1967 he saved the wildlife on Aldabra, an Indian Ocean atoll, by preventing the building of an RAF base. In 1968 he leaked information about Porton Down chemical warfare laboratory to a newspaper, causing classic scenes of parliamentary uproar. It would not be the last time.

It was that indefatigability that counted against Dalyell in terms of a wider press and public (not that he minded). The former Labour MP Chris Mullin had similar interests, but leavened his devotion with a self-deprecating humour; Dalyell’s often apparently one-man campaigns made his name but rendered him too easily as an eccentric whose predictable protestations were easy to discount.

Dalyell was and remained the most prominent anti-devolutionary Scot. In the late 1970s, his opposition to his government’s part-principled, part-desperate legislative courting of nationalist support in the Commons was based on a straightforward political principle which Enoch Powell ensured should become known after Dalyell’s constituency: the West Lothian Question. It essentially asks why MPs from devolved regions have the same voting rights in the Commons as English MPs now that English MPs are excluded from voting on devolved issues.

As with many of Dalyell’s questions, for those in power it was a question they’d really rather weren’t asked. Certainly the then prime minister James Callaghan, whose administration fell in part through the consequences of Dalyell’s exertions, wished he hadn’t. Forty years on, despite some interest in the subject, it still hasn’t been answered.

Stalking Thatcher

Dalyell’s concerns were with Misrule, as he called his 1987 book: “the personal behaviour on public matters of one particular party leader and prime minister. It is about her truthfulness to people, press and parliament. And on being ‘personal’ in this matter I offer no apology”.

He accused Margaret Thatcher of serial dishonesties. There was the sinking of the Belgrano during the Falklands crisis (1982), in which he held that the Royal Navy had been ordered to sink the Argentinian cruiser to scuttle an incipient peace process. There was the Westland affair in 1986, when Dalyell harried Thatcher over undermining her secretary of state for defence – Michael Heseltine – more effectively than did his party leader Neil Kinnock.

On Libya (1986), Dalyell vociferously doubted the stated reasons for Britain accommodating US president Ronald Reagan’s air strikes against Colonel Gaddafi. He defended the BBC against attempts by the government to prevent broadcast of a documentary about the spy satellite Zircon (1986-7). He also defended the former intelligence officer Peter Wright after the government tried to prevent publication of his Spycatcher memoirs about his years in intelligence. For Dalyell, Thatcher was “a bounder, a liar, a deceiver, a cheat and a crook”.

A constant presence in broadcasting studios and the Commons – expulsions permitting – Dalyell’s tirelessness deserves, at the very least, several footnotes in the history of 1980s Britain. No critic of Thatcher was so assiduous. It was more revealing of her than of him that she omitted mention of him in her memoirs.

Dalyell’s time in parliament spanned Labour’s years of power in the 1960s and 70s, the internecine impotence of the 1980s, and the morning glory of New Labour in the 1990s. An inveterate critic of his final prime minister, he was happy to declare Tony Blair the worst he had known. Standing down in 2005, Dalyell happily missing the disintegration of the last Labour government.

Dalyell wrote a good biography of his Labour Party mentor Dick Crossman. He was a regular obituarist for The Independent, seemingly accounting for every parliamentarian who died in the last 30 years.

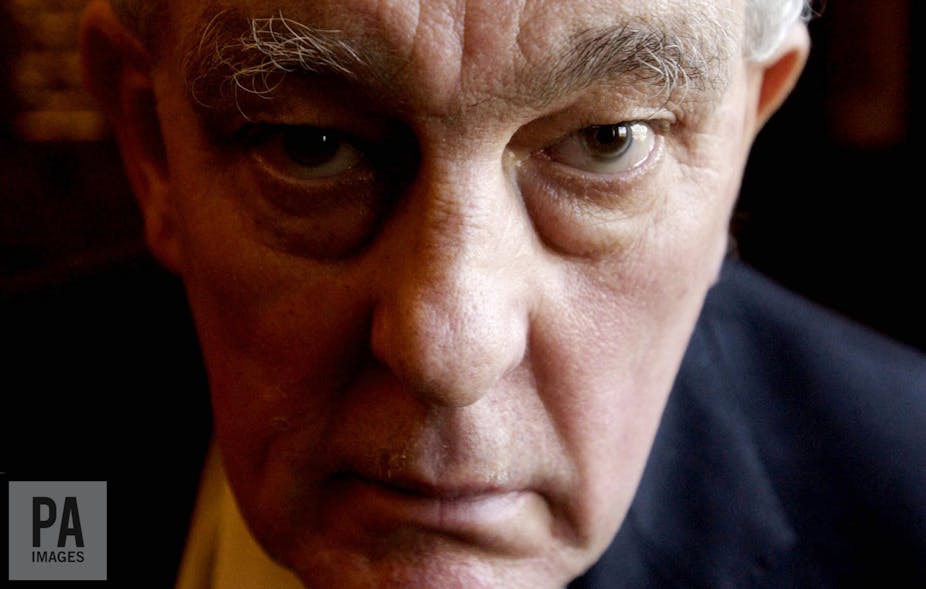

Lugubrious of manner, distinctive of accent and with a bone-dry wit (his 2011 autobiography was entitled The Importance of Being Awkward). For all that he evokes a bygone age of licensed eccentricity where unbiddable private members challenged the Treasury bench, Tam Dalyell wasn’t really a “type” at all.