The 74,000 hectares of Tasmania’s controversial World Heritage extension will not be delisted as requested by the Tasmanian and federal governments.

At the meeting of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee in Doha, the decision to reject the proposal was made in under ten minutes late on Monday (overnight Australian time), with reportedly no objections from any members of the Committee to retain the areas in World Heritage. In rejecting the move, Portugal condemned Australia’s request as “feeble”.

The story so far

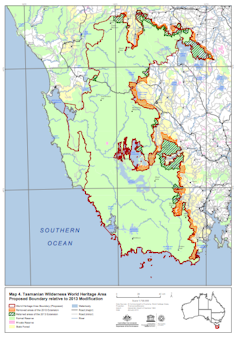

Under the previous state and federal Labor governments, 172,000 hectares were added to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area as a “minor boundary modification” under the Tasmanian forest peace deal. The extension was accepted into World Heritage at a meeting in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in June last year. The decision included a request that Australia undertake more study of cultural heritage values, in consultation with the Tasmanian Aboriginal community.

There was some concern in the International Union for the Conservation of Nature that the size of the extension (more than a 10% increase in the area) was not “minor” and required more time and resources for a complete assessment.

In the lead-up to the 2013 election, the current federal government sought to have 74,000 hectares of the area delisted, on grounds that it includes degraded forests unworthy of World Heritage.

While debate has centred on forests, the extension may also satisfy a suite of other criteria for inclusion in World Heritage, including unique geology and important indigenous cultural sites.

New information on degraded forests

Previously on The Conversation, Tom Fairman examined just how much of the area to be delisted contained “degraded”, previously logged, or plantation forest. At the time we only had so much information — primarily the amount of eucalyptus and pine plantation in the World Heritage area, which turned out to be less than 1% of the area proposed to be excised.

Since then a Senate Inquiry, headed up by Labor and the Greens, allowed some numbers to be put on the extent of forest resulting from former logging and other activities. The data was drawn from environmental groups, state and federal authorities.

This information was relayed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature brief to the World Heritage Committee.

IUCN advised against delisting, indicating that of the 74,000 hectares, approximately 10% had been logged since the 1960s (when reliable records began). However, 44% of the area is considered to be old-growth forest – that is, ecologically mature forest where the effects of disturbances are now negligible.

The remainder of the 74,000 hectares is a mix of:

- unlogged, but not old-growth, native forest - like regrowth from bushfires (15%);

- forest potentially logged more than 50 years ago (6%);

- rainforest (8%); and

- grasslands and non-forest (17%).

The International Council on Monuments and Sites advises the World Heritage Committee on cultural properties, landscapes and archaeological values. They advised against the listing until assessment of cultural values in the proposed extension. This led to the World Heritage Committee to release a draft decision in May rejecting the proposed boundary modification, and it was this decision the Committee adhered to.

What does the decision mean for Tasmania and its forests?

The decision to support retention of the World Heritage extension will come as relief to the conservation groups that have campaigned for the area to be protected for many decades.

It is expected that the additions will remain as “Future Reserve Land” tenure until they are formally reserved, as was the case with the extension in 2013. However, the creation of new reserves is pending management plans and consultation with communities.

But here are other considerations now that these areas remain World Heritage. For instance, World Heritage protection does not necessarily guarantee the forests are “locked up” from all forms of development.

For example, the Great Barrier Reef was recognised as World Heritage over three decades ago, and is managed for commercial activities such as fishing, tourism and shipping under regulated conditions that should maintain its World Heritage values. At the meeting in Doha, a decision over whether to list the Reef as World Heritage “In Danger” due to port developments was delayed until 2015.

It has not been done in the past, but in Tasmania, timber harvesting could occur in these areas if undertaken in a manner which maintains their World Heritage values. This will be an area to watch in coming years, though statements from the federal and Tasmanian governments indicate that they will respect the World Heritage decision despite the forest policy landscape having shifted substantially since the last Tasmanian election.

It is also important to remember that placing forests in a certain conservation land tenure does not necessarily protect them from catastrophic wildfires, invasive pests or diseases which may be made worse by climate change. For example, in other parts of Australia, we have seen some of our most treasured National Parks suffer serious biodiversity loss and repeated bushfire damage.

Therefore, even without timber extraction, these forests will need active management to ensure their resilience to a changing future. This does not always come cheap – the cost of management tends to be overlooked in decisions to change conservation status. In fact, park management agencies are having to manage larger areas with fewer resources, an alarming trend that has been identified for some time.

So while the battle to protect these forests in World Heritage may be won to the relief of many, it is by no means the end of ensuring the protection and future security, in perpetuity, of these forests.

The authors would like to thank environment and heritage consultant Peter Hitchcock AM for providing updates on the proceedings and decisions from the World Heritage meeting at Doha.