It’s three o’clock and you are picking up your son from school. The bell rings. A class of six-year-olds charges out of the building. And you have absolutely no idea which child is your son. They all look exactly the same.

This is not a scene from a low-budget horror movie, but how it feels to have face blindness. It is actually remarkable that most of us are so good at discriminating between faces, since they are all approximately the same – two eyes above a nose above a mouth. Our visual system has had to become highly sensitive to very subtle differences between them. It’s not foolproof, which is why we often see faces in inanimate objects.

Face blindness, also known as prosopagnosia, affects as many as one in 50 people – upwards of one million in the UK alone. Some are born with the condition, while others develop it after a stroke or serious head injury. Either way, sufferers can have otherwise normal vision.

Since faces and their expressions allow us to read someone’s emotions and judge their state of mind, face-blind people are at high risk of social embarrassment, isolation, anxiety and depression. They have to develop strategies to cope, such as recognising people by their hair, height, clothes, posture, gait or voice. And still they can be vulnerable – if a friend gets a new hairstyle, for example, they can become unrecognisable.

Though the condition is not curable, it can be very reassuring to be diagnosed and have the nature of the condition explained. Once the person has told those around them, it often makes them less anxious about being labelled arrogant or rude. It means healthcare workers can show patients new strategies to compensate, such as trying to deal with individuals rather than groups of people, and interacting with the same person each time where possible – sticking to the same GP, for instance.

Some reports also suggest that intensive training may help improve their facial recognition, though this has not been widely available to date. Then there are legal implications, since someone with face blindness will not be much help at an identity parade.

A testing problem

It’s actually not easy to test face perception well. Some tests use photographs, but the viewer can get clues from things like clothing or facial expressions. Other tests rely on memorising faces, but again that could be a result of memory rather than face blindness. These tests tend to be much better at dividing the world into people with good and bad face recognition than grading the wide spectrum that likely exists. They also take between ten and 15 minutes, which is not ideal for health professionals.

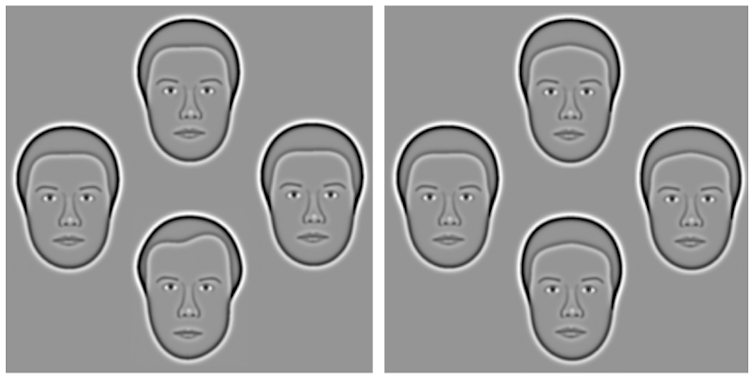

We recently developed a new test that avoids these shortfalls. It uses simplified face images that have been synthesised from ordinary photographs. Unlike photographs, however, they can be very precisely modified to make the faces more or less different from one another. It takes only four minutes from start to finish.

Participants are tested on their ability to tell the odd one out among four faces on a computer screen, cycling through 30 different sets over the duration. The computer monitors show how well the participant is scoring on each set of faces and adapts the difficulty level using an algorithm. Those scoring well get increasingly more similar faces, while strugglers get less similar faces until the test converges on precisely how sensitive someone is.

If you look at the two sets of faces below, for instance, the left set is much easier to differentiate. About 95% of typical adults would be able to spot that the face on the bottom is the odd one out. In the set on the right, only about 25% of typical adults are able to choose the left-hand face correctly.

What we found

We tested 52 young adults with no known face-perception difficulties or eyesight or neurological problems. Some turned out to be highly sensitive to small face differences, while others much less so. This confirms that face perception can vary substantially between individuals who are not face-blind.

We then tested a female patient who did have lifelong difficulties with face recognition. When she took some of the established face tests, her score was statistically just outside normal. But the Caledonian face test scored her several times poorer than the norm – even the poorest person in our main group was approximately twice as good at telling faces apart.

In short, our test potentially offers two kinds of benefits. First, it offers a much more sensitive way of detecting face blindness than the current alternatives. Not only could this help healthcare workers decide what level of intervention is necessary, it can be a tool for the intensive training we mentioned earlier: because the test faces are constantly altered by the algorithm, participants can use the test a number of times without becoming familiar with them.

Being able to differentiate between the face-recognition abilities of “normal” people is useful as well. It may help identify people who are particularly good with faces. The police are beginning to use these so-called “super-recognisers” to review CCTV footage to connect different crimes, while they could also be helpful at border control, for example. Differentiating abilities could also lend more or less weight to different identification witnesses in court cases, of course.

The test is also quick to administer and suitable for use by optometrists, GPs, psychologists and neurologists. It is ready to be used with adults up to the age of 50, while we’re currently doing more work into face recognition in older people. We are optimistic that a major step forward in this field could now be within reach.