Conversation is civilized speech. It is more purposeful than chatter; more humane than gossip; more intimate than debate. But it is an elusive ideal.

In our verbal exchanges we often flip from one topic to another – while conversation suggests something more sustained, more substantial.

A conversation is the encounter of two polished minds: tactful enough to listen, confident enough to express their true beliefs; subtle enough to search out the reasons behind the thoughts.

A conversation is a work of art with more than one creator. So, quite often, two or more people cannot rise to the level of conversation. They talk with one another. It may be cheerful, it may be polite, it may be a bit funny, it may be informative. But it lacks something crucial to conversation: the risk of seriousness.

Secretly we yearn for real conversation, because we long to encounter the best and most substantial versions of other people. We long for the truth of our selves to be grasped and liked by another person.

A classical conception of conversation takes convergence as its final – if distant – goal. When intelligent, reasonable and cultivated people disagree there is almost always some hidden confusion or failure of evidence that explains the lack of harmony. But with time and care these failings can be made good. Classical conversation is the mutual aid in the joint pursuit of the truth.

An interim benefit of such conversation is the light it sheds on what decent people really actually do disagree about. And more than that it illuminates the intimate why: the motives, fears, hopes, associations, key experiences, leaps of logic and quiet deductions – all of the things that add up to explaining why a serious person holds the view they do.

This is surprisingly rare. How often, really, do we appreciate why someone thinks as they do?

This is why true conversation is not quite like a debate. In a debate one feels that an argument has priority. In conversation it is the person that comes first. And though our traditions of law, science and scholarship, and even of politics, make a noble cause of putting the argument first, there is something they lose along the way.

In the end, all beliefs are the beliefs of individuals. This does not establish truth – for what is the case is the case whether anyone assents to it or not.

My point is the worth of a truth, the significance of an idea, the power of a belief, depends on the inner life of the person who holds it. And if we do not know about that inner life, we do not really know that idea.

But this is to move from the classical to a more romantic ideal of conversation. The finest talk with another person is the search for soul-companionship.

The most tender-ideal vision of conversation is given by Tolstoy’s hero Levin in a moment of great personal happiness: try to see what is precious to the person you are conversing with and you will discover that it is precious to you as well.

In a 1962 essay, the political philosopher, Oakshott, advanced a rather wonderful vision of an entire culture as a kind of conversation. And the vision gets its power from being – I think – a lovely distortion. It is not so much true to the facts as true to our hopes. It is how our culture might be, if it were improved.

As civilised human beings, we are inheritors, neither of an inquiry about ourselves and the world, not of an accumulated body of information but of a conversation, begun in the primeval forests and extended and made more articulate in the course of centuries.

It is a conversation which goes on both in public and within each of ourselves. Of course there is argument and inquiry and information, but wherever these are profitable they are to be recognised as passages in this conversation, and perhaps they are not the most captivating of the passages.

Conversation is not an enterprise designed to yield an extrinsic profit, a contest where a winner gets a prize, nor is it an activity of exegesis; it is an unrehearsed intellectual adventure.

Education, properly speaking, is an initiation into the skill and partnership of this conversation in which we learn to recognise the voices, to distinguish the proper occasions of utterance, and in which we acquire the intellectual and moral habits appropriate to conversation. And it is this conversation which, in the end, gives place and character to every human activity and utterance.

I think, though, that more weight should be given to the consequential benefits of good conversation. There are things worth loving other than intellectual adventure.

Still, taking inspiration form this grand utterance, perhaps there are many parts of this great conversation which need attention.

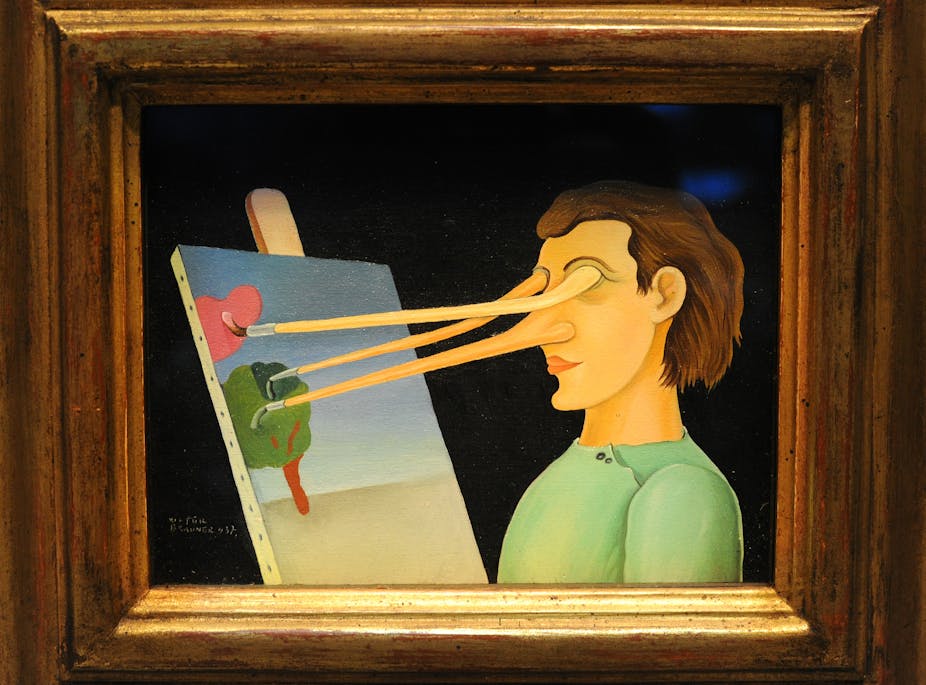

For years, I’ve been longing to get into a big, sustained conversation about art. I have heard, in my life, an embarrassing quantity of talk about art; I have heard (I should think) just about every possible point of view set forth and maintained with deep conviction.

I have heard every view disparaged. But I have, to be honest, heard hardly any conversation about art. That is conversation that tries to get to know an alternative point of view, that is curious to find the best expression of its own opinion – not just the most strident or most celebratory.

One of the most precious aspects of conversation is that it does not presuppose agreement. It presupposes civility and sincerity. Painfully often we preach to the choir. We advance our views in ways designed to make those who already agree with us cheer. Conversation has something of the missionary about it: it is interested in meeting the unbeliever, the sceptic, the doubter, the opponent.

So here’s my idea. I’d like to pursue the great conversation about art. And I’d like to start with the central question: how should we define art? Otherwise we won’t be sure what we are talking about.

The great conversation spreads out to embrace a wide range of issues: why is art important - if in fact it is? One what grounds, if any, can a work of art be correctly described as great? Who decides what counts as good art, and are they right people to do so.

Should the state subsidise art? If so, what modes of support are most effective? And these questions grow out of, and into, a million others – about exhibitions, galleries, favourite postcards.

But the point is not merely to spread out. The aim of great conversation is to organise, to connect, to unify – even, dare I say it, to simplify.

So speak to me. How should art be defined?