The Australian government announced on Sunday it would introduce a carbon tax at $23 a tonne next July, rising 2.5% annually plus inflation and moving to a market-based emissions trading scheme in 2015.

Under the plan, which has been fiercely opposed by several heavily polluting industries and Coalition leader Tony Abbott, a $3.2 billion renewable energy agency will be created. It will manage some consolidated existing funding for renewable energy development, topped up with new funding.

The carbon price will raise $24.5 billion over its first four years but will not be revenue neutral, putting the budget $4 billion in the red, the ABC reported.

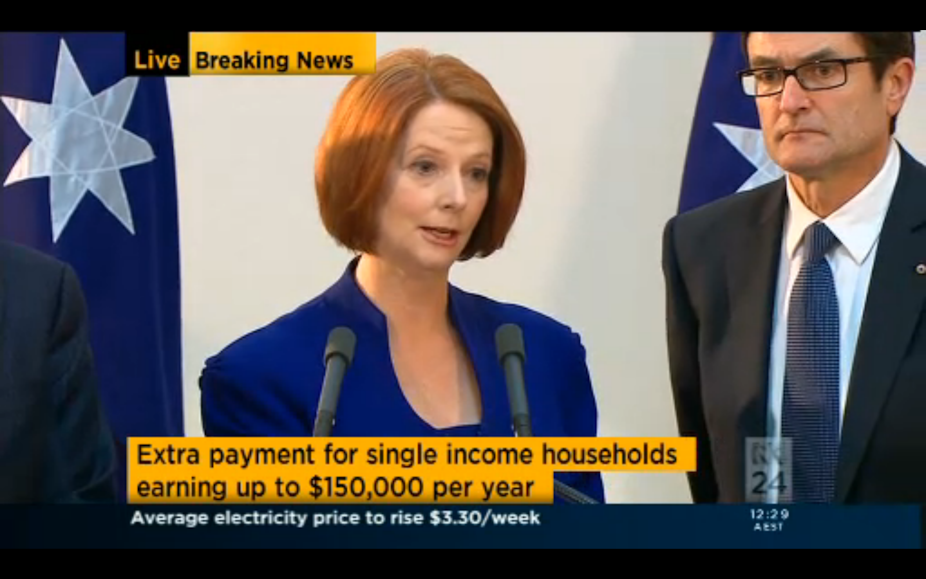

To sweeten the deal, the government has proposed raising the income tax-free threshold to $18,000, as well as other tax cuts and compensation for nine out of 10 households, said Prime Minister Julia Gillard.

Many of the proposed tax reforms are based on a review by former Treasury secretary Ken Henry.

Treasury modelling predicts the tax will cost households around $10 a week and will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 160 million tonnes by 2020, Ms Gillard said. The government aims to reduce emissions by 5% from 2000 levels by 2020 and by 80% from 2000 levels by 2050.

The tax will be paid by 500 companies – half the 1000 initially slated for carbon tax eligibility – and agriculture and petrol will be exempt.

The deal will be put before parliament in August and is expected to pass with approval of several independents. It will also pass through the Senate, thanks to the support of the Greens.

Dr Ross Garnaut, the government’s chief economic adviser on climate change, responded to today’s announcement here.

We asked the experts to respond to today’s announcement:

Dr Neil Perry, research lecturer in corporate social responsibility and sustainability, School of Economics and Finance, University of Western Sydney

I don’t think the incentive effect of it is really going to do much because it seems most producers will pass the price on and, due to the compensation, no one will have to pay that price. So there’s not much incentive for change. Real after-tax wages will stay constant and everyone will still buy as much. The price would need to be much higher to incentivise change.

I think the idea of buying out the really polluting energy producers is a really good one. More of that would have been good. I haven’t looked at the details yet, but it seems someone can bid for the capacity that will be freed up, so it sounds like cleaner producers, more efficient producers will be able to pick up that capacity. This could work well, particularly if the plan supports the workers.

Using some of the funds to pay for clean energy products and the loan fund seem like a great idea. But I would say that the support for polluting industries probably isn’t justified. The funds not going to households should have gone to renewables, not to protecting industry that shouldn’t be protected.

I worry about the overall impact of protecting the profits of industries that really shouldn’t be protected. If they’re dirty manufacturing, they shouldn’t be here. Shutting them down will have a major effect on their particular workers, but there are certainly ways to assist them. It could have been a long-term adjustment, it wouldn’t have had to be a shock.

But you’ve got to start somewhere – it’s better to have something rather than nothing.

Professor John Quiggin, School of Economics, University of Queensland

The proposed carbon tax is a substantial improvement on the heavily compromised emissions trading scheme agreed between the Rudd government and the Opposition under Malcolm Turnbull. Although there is substantial compensation for emissions-intensive industry, it is temporary and based on historic emissions levels, so that the incentive to reduce emissions is not compromised.

The design of the compensation package for households is also welcome. The government has avoided the temptation to pretend that everyone will be better off, and has taken the reasonable position that high income households do not need to be compensated for the introduction of necessary reforms. This has permitted the very welcome measure of raising the income tax threshold and thereby taking more than a million low-income workers out of the income tax system.

While the primary focus of the package is, correctly, on the imposition of a price on carbon emissions, there are a range of supporting measures designed to encourage energy efficiency and innovation. On the whole, these seem more carefully designed than the measures introduced under previous governments.

While the package will drive substantial changes in patterns of energy production and energy use, the overall impact on the economy will be so small as to be undetectable against the background of year to year variations in levels of economic activity driven by factors such as exchange rate movements.

Dr Ben McNeil, Senior Fellow, Climate Change Research Centre, University of New South Wales

Generally, what we needed to see was something which was a good starting price, a price that could be effective and manage the transition from what we do today to what we want to do in the future. The government’s really nailed it.

I’m particularly encouraged by the international credits plan. In the CPRS [proposed by Rudd],companies could buy credits – offsets - from overseas for up to 80% of their activity, and it’s now down to 50%. That’s very important because we want the transition to happen in Australia, not overseas. We want companies to invest here at home, not in some potentially dodgy scheme overseas. Had we stayed at 80%, that leakage would have been my major concern. In an ideal world, overseas offsets would be 0%, but at our current state 50% is meaningful. The plan will have to manage what the offsets are and their quality, but generally for flexibility - given we’ve never had a carbon price - 0% wouldn’t be very sensible at this point. Businesses need a bit of flexibility.

For the coming three years, we won’t know how much this will affect emissions. The modelling can’t do it accurately enough: it depends how much companies change, some may just pay the price. But once the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) comes in, we’ll start to have some certainty on what the cuts will be. But even now, this is a good thing to get companies thinking about what they’re going to do.

The one thing I’m encouraged by is that we’re going to have a relatively broad price once the ETS comes in. We’re not talking about a price that will just change how we generate energy, but how we design our homes, our cars, the types of fuel we use, our building materials, plastics: it will all be part of the scheme. All those areas – not just energy - will start to innovate into a low carbon space. Then we have the capacity to have new industries in those areas, not just in renewable energy. A price will lead us to innovate across an entire society and all sectors.

Professor Mahinda Siriwardana, School of Business Economics and Public Policy, University of New England

Overall, this price is a very good outcome. In my modelling, I looked at $30 per tonne and I think $23 per tonne is a reasonable price to start with. It gives reasonable revenue to the government. It will provide the revenue to do most of the things they’re proposing in the plan.

I didn’t expect the proposal of an 80% cut in emissions by 2050. This is a great outcome if we can achieve it; earlier the proposal was 60%. While it’s very hard to predict whether we can make these cuts, anywhere between 60% and 80% will be very good.

There is a major tax reform in the tax-free threshold change. This is a major breakthrough with minimal administrative complexity for the government. This will include many low-income families who would otherwise be affected severely.

The plan is not budget neutral because there will be $4 billion funding needed from the budget for some of the work they’re proposing. The government will have to pay up front for pensioners and some industries, before income is generated through the tax. But compared to the overall budget, this up-front payment is a very small proportion.

The question now is how this will be sold to the average person, because most people won’t want to read this whole report. It has to be done intelligently so people can understand the impact. So far, the Prime Minister has done a very good job today of explaining it. Overall, it’s a very good start – I was very pleased.

Professor Michael Dirkis, taxation Law expert from the Sydney Law School, University of Sydney

What we have seen is effectively the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) that was advanced by former Prime Minister Rudd with some minor changes round the edges. The bigger changes are in the area of the compensation package and the changes to the tax law.

The government has been careful to say it’s a price, not a tax. It’s a permit system whereby people pay per tonne and what we see in three years time will be the full a cap and trade system come on board. In that sense, it remains an ETS.

The levels of compensation couldn’t have been achieved if we had gone down a pure carbon tax model because of issues with the World Trade Organisation and compensation for trade-exposed emissions-intensive industries.

The thing that is of greater interest is the government taking an opportunity to clean up the tax rates and, in one sense, simplify the overall feel of Australia’s income tax system.

In the Howard years, whenever you asked ‘What is my tax bill likely to be?’ you had to make a determination of whether someone was married, how many children they had, their age, whether they were retirees or not and your rate would vary.

Introducing a high tax-free threshold and the adjustments means that there hasn’t been a shift in the amount of tax most people pay but there’s a more understandable system and it means that a million people fall out of the tax system.

So there’s a massive compliance cost reduction at the community level. People aren’t paying $60 or $100 to get their tax returns prepared and we are not paying for the Tax Office to process a million tax returns that were unnecessary.

On the initial carbon price, I think there needed to be a compromise price. Obviously the Greens wanted a more heavy entry point. $23 a tonne is a compromise and there are lot of exemptions to the system that weren’t there on the previous model. It has a built-in inflation rate of 2.5% per year and then going to the market mechanism setting the price in 2015.

It delivers a major boon for the financial services industry because of the opportunities for hedging and a range of products around the permits market.

I think they have got the balance [between curbing emissions and compensating people] right. The group that is likely to lose is those earning $150,000 per family. They are not the government’s traditional voting bloc and they were subject to most of the trimmings in the last four Labor budgets.

The greatest risk will be the extent to which the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) can stop price gouging. That was one of the big threats when the GST came out. It will be the ACCC’s job to make sure that people are not marking up their prices too much to compensate for the carbon price. There’s the potential for multiplier effects to flow through.

The devil is in the detail. That’s when we will know the impacts on secondary markets but my initial reading is that the financial services industry will be happy.

David Stern, Crawford School of Economics and Government, Australian National University

The package is pretty comprehensive. While the coverage of the fixed carbon price – 500 businesses – is not that big, other initiatives such as measures for renewables and biodiversity will cover some of the omissions. The package certainly includes lots of things that weren’t in the CPRS, despite dropping petrol and removing half the businesses covered.

The increase in the tax-free threshold is a huge change to the tax system; I’d say this is the most significant component, and a step towards the recommendations of the Henry Review. It will be huge for most tax payers.

As a result, I can’t see how this can be revenue neutral, it’s going to be a cut in taxes. It’s not like the Opposition can say it’s a big new tax; in fact, it’s kind of the opposite.

The big exemption is petrol, which is logical, and in the long run, it might not matter that much. This is because if other countries do stuff that drives innovation towards more efficient vehicles and electric vehicles, we’ll start using those. That kind of innovation wasn’t going to happen here anyway.

When we think about the scope of the scheme, it’s good to remember that Australia is a bit different in that the largest companies use so much energy as a proportion of the economy. It’s a huge percentage that the top 500 companies use, a huge part of the emissions in the economy. So targeting 500 businesses will actually cover a lot of what we emit.

Dr Chris Riedy, Director of Institute for Sustainable Futures at University of Technology, Sydney

They have obviously seen it as an opportunity to pursue a social justice agenda on taxation, as well as an opportunity for carbon pricing. That’s a way to negate some of the attacks on the cost of living impacts. I think that’s a smart move, to tie it to an overhaul of the tax system.

I would have liked to have seen a faster escalation in the price over the first few years. I think $23 a tonne is very much a softly, softly approach and isn’t going to drive a lot of new investment in clean energy.

One thing that’s really important is to see how much of the funding is going to support clean energy directly.

It sounds like there might be some new funding for renewable energy because I saw figures last week of $2.3 billion for a renewable funding agency [as opposed to the $3.2 billion announced today]. So I would say there is a bit of new funding in there. But I would like to see more direct funding for renewable energy because at those carbon price levels it will not do a lot to support investment in renewable energy.

Dr Paul Burke, Crawford School of Economics & Government, Australian National University

I think it’s a good package – an important package to green our tax system. I think the price is as expected, it’s a good start.

The increase in the tax-free threshold is a good idea. It’s an efficient way to return revenue to people and reduce their tax. One million people won’t have to submit a tax return at all, which saves time for them, and a burden on the administration at the other end.

The concessions are slightly over generous to coal, but if that’s the cost of getting reforms it’s worth it. Some of it just may be the cost of getting through an important structural reform.

Economists have been pushing for this for a while.

The balance is right, the price is reasonable, and it will increase over time as we move to an ETS. Assistance to households at 50% is good.

I think many people won’t notice the effects of the carbon price, especially consumers. But there will be lots of important impacts on production, by changing the relative costs of electricity and influencing production decisions.

Anna Skarbek, Executive Director, ClimateWorks Australia, Monash University

I’m really pleased. It’s a very sensible package. There’s a lot in it. Overall, I think it’s a very sensible architecture, encouraging financial support not just for households and industries but in new technology. I’m also pleased about the investment in the land sector, in biodiversity, and in the carbon farming initiative.

That sort of investment should work very well to unleash the activity it’s designed to trigger. Substantial investment into additional R&D into soil carbon and abatement in agriculture is a very worthwhile thing.

The most important thing is the long term mechanisms and targets. We will have a sensible transition to a floating price, with quite robust governance and transparency for setting future caps.

To get something like this through, there has to be compromise. But the most important is the architecture and the certainties it provides about price signal arrangements for investors over the long term. The short term assistance simply helps us move towards that – it’s a transitionary measure for industries.

The new commitment to reduce emissions by 80% on 2000 levels by 2050 is very pleasing. The independent authority must now take that into account when setting each five-yearly carbon budget.

Australia has a great opportunity to reduce emissions, and ClimateWorks is really keen for us to get going on that. This package will certainly help accelerate efforts and build momentum across all sectors, and engage in the opportunities this presents.

Professor Warwick McKibbin, Director, Research School of Economics, Australian National University

It’s broadly consistent philosophically with what I have been arguing for 20 years. I support the principles involved but there are some problems in detail.

The big question you have to hold up to assess this program is: is there any way of knowing now what firms might expect the carbon price to be in 2020 or 2030? The answer is no, there’s nothing that drives a futures price yet.

That is a real problem because that is where the technological innovation will come from. [Companies] have to have some way of knowing what price will be expected at any point in time. Tying down the long term expectations hasn’t been done. That could still happen once they put in place the carbon trading market but they have to do that in a particular way.

Problem number two is I think there is too much churning of revenue. I would give out 50% of the permits to households and 50% to industry. But they are taking it as auctioning the permits, taking the revenue and then using it to give people dollar amounts. You could have just allocated permits without that much churning.

The third point is I think there is an enormous amount of money going into renewables. They have set up both research into renewables and land use. Is that where you really want to focus your attention? There’s a debate to be had on that but I think the carbon price can drive a fair bit of that itself.

Fourthly, if you look at the actual details of the modelling, by 2020 about two-thirds of the abatement is actually done overseas from us buying permits from foreigners. Only a third is domestic. That is in the treasury modelling.

If you believe the assumption of the modelling, there will be a substantial permit trading market out there, which I disagree with. The reality is, you will probably only still be dealing with CDMs and CERs.

[Spending so much on overseas pollution permits] means your revenue base will be greatly diminished, which means what we are seeing in the hand-outs has got to be something that will not last for very long. We won’t have the revenue base to pay for it.

If you are doing it that way, then how much would you expect there to be penetration into the Australian economy of non-fossil fuel energy?

The final point is I think the price is too high. In my modelling, we start at $15 a tonne for Australia, rising by 4% a year and that gets us to the 2020 target of a 5% reduction on 2000 levels [of pollution].

If you exclude things from the program, like oil, then of course you have to have a higher price to get the same amount coverage. I don’t think there should be any exemptions.

Overall, though, I think the modelling is pretty good, the broad package looks pretty good in terms of the broad principle but the details could be improved to get lower costs for the economy.

The following comments were collected by the Australian Science Media Centre:

Professor Snow Barlow, Convener of the Primary Industries Adaptation Research Network and the Melbourne School of Land and Environment at the University of Melbourne

This is a well constructed government policy addressing climate change through an immediate price on carbon, transitioning into an emissions trading scheme, thereby enabling the government to cap emissions to a level that enables us to meet our agreed five per cent cut in emissions in 2020.

The budget-neutral package redistributes the estimated $10 billion pa revenue between potentially disadvantaged communities, export exposed emissions-intensive industries and innovation to enable the transition to a low-carbon economy. This innovation package is comprehensive both in magnitude and coverage.

The specific Creating Opportunities for the Land package provides a welcome $1.9 billion over six years to support emissions reduction and carbon sequestration in the land-based sector. More than $200 million over six years is allocated for research and development to develop strategies, technologies and methodologies to achieve these emissions reductions.

The implementation of these measures will be guided by natural resource management (NRM) plans for each of Australia’s 56 NRM regions to ensure that carbon emission reduction measures do not result in perverse outcomes for land use and Australia’s unique biodiversity.

Most importantly there is a clear market for the carbon credits developed in these activities either directly into the Tax scheme or through a scheme regulator in the case of activities not currently covered by the Kyoto Protocol.

Professor Peter Newman, Director of Curtin University’s Sustainability Policy (CUSP) Institute

I think it’s fantastic that we have a climate change package which includes a carbon price for the front end of the economy and a range of end user initiatives to assist with the transition for households and businesses. It’s been a painful process but an historic day now that we have the package.

Well done to the Government, the Greens and the Independents! They have been real leaders for a change. I hope Australians will recognise that this is a necessary step for us, that the world needs us to be responsible and demonstrate hope like this and that the Opposition’s negativity is based on fear – which never makes good public policy.

Professor John Cole, Director of the Australian Centre for Sustainable Business and Development at the University of Southern Queensland

It has more than a few rough edges and shows all the signs of the political trade-offs needed to secure a carbon price in one of the most carbon-intensive economies on the planet.

In creating a politically defensible platform from which to lead and steer change as well as resurrect its standing with the Australian people, the Government has traded away some economic and environmental efficiency to placate the coal interest, at least in the short to intermediate term.

That said, today’s carbon package is a welcome and significant first step by Australia on the road to decarbonising its economy as the international community slowly but surely comes to grips with the human dimensions of climate change.

There is no shortage of targeted assistance measures to help a range of industries do what they should already be doing, namely achieving savings through energy efficiency, capturing fugitive emissions for co-generation, and planning for competition in a world which will increasingly value low-carbon products and services.

The overall outcome is a politically practical no-frills deal which recognises that there is no silver bullet for dealing with the complexities of climate change, economic reform and decarbonisation.

Professor Peter Cook, Chief Executive of the Cooperative Research Centre for Greenhouse Gas Technologies, Canberra

I am glad to see that clean energy technologies will be supported through the carbon tax, but concerned that carbon capture and storage (CCS) is not included in the remit of the new Clean Energy Finance Corporation. CCS is a clean energy technology that is highly relevant to decreasing emissions from biomass, gas and coal; there are also potential opportunities for combining CCS with geothermal power and algal sequestration. CCS is likely to be a key component of moving to electric cars and the hydrogen economy and the increased uptake of gas.

All the projections of bodies such as the International Energy Agency clearly show that we will need CCS for at least 20 per cent of the global mitigation effort in the coming decades. The proposed arrangements suggest a more polarised approach to lowering our carbon footprint. Without inclusion of CCS, there is no solution to the greenhouse issue.

The clean energy future for Australia has to be greater energy efficiency, increased use of renewable, switching to gas and carbon capture and storage. People have to be realistic about the clean energy mix and what the various technologies can achieve, and whilst they might like renewable energy to be the answer, the reality is that for decades to come it will only be part of the answer. The steps proposed as part of the carbon tax measures should reflect this reality and include CCS as an important component of future energy mix.

Professor Ian Lowe, Emeritus Professor of Science, Technology and Society at Griffith University and President of the Australian Conservation Foundation

Today’s announcement is a very important step forward. There will at last be a price on greenhouse pollution. While it does not start high enough to drive a rapid transition to a clean energy future, it is a beginning and a clear signal to the business community. I particularly welcome the establishment of a new Climate Change Authority to advise on pollution caps after 2015, improving the chance they will be based on science rather than political expediency. We need to do much better than a five-per cent reduction by 2020 to meet the urgent challenge of climate change.

The Clean Energy Finance Corporation and the Australian Renewable Energy Agency are important mechanisms for driving the transition to low-carbon energy. The National Energy Savings Initiative needs to be rapidly implemented, as energy efficiency is by far the most cost-effective way of reducing greenhouse pollution. We should also welcome the commitment to take account of the voluntary action by millions of Australians in setting future targets. The new Biodiversity Fund is a crucial investment in our capacity to protect Australia’s unique biota from the accelerating impacts of climate change.

There are some disappointments in the package, especially the continuing support of polluting industries like coal-fired power and LNG. While road transport fuels are excluded from the carbon price, rail is not, so the existing huge public subsidy of road freight will be increased further. An urgent priority should be the phasing out of subsidies for fossil fuel production and use.

Ratifying the Kyoto Protocol in 2007 was the first step to joining the international effort to slow climate change. Today’s announcement is the second step. The new package deserves support.

Professor Graham Farquhar from the Australian National University Climate Change Institute

The aim of the carbon tax is to reduce Australian emissions by five per cent. In turn, the aim of that reduction is to put political or economic pressure to encourage or shame other countries to reduce their emissions by five per cent. If we are successful and all the countries of the world reduce their emissions to five per cent below what they would have been, then the anthropogenic climate that we would otherwise have seen in 2031 will be postponed until 2032.