If you had to argue for the merits of one Australian book, one piece of writing, what would it be? Welcome to our occasional series in which our authors make the case for a work of their choosing. See the end of this article for information on how to get involved.

Miscarriage is a subject that generally makes people feel uncomfortable. It may even be one of the last conversational taboos – too difficult to talk about, despite the fact we live in a modern world which has come to be defined by the over-sharing of private details in public (generally “virtual”) spaces.

The death of an unborn child is a form of grief and loss that is hard to articulate, as it signifies the end of something that never really had a chance to begin. And until you experience a miscarriage first-hand, you may never appreciate how profound a loss it can be.

All of which serve to make it a provocative – or, at the very least, highly unusual – topic for a book aimed at young adult audiences. In the hands of a less skilled author, the results may have been disastrous. But Sonya Hartnett’s The Ghost’s Child (2008) is a whimsical and poignant modern fairy tale that celebrates feminine experience and strength.

It is a story of loss, most certainly (of a child and also a marriage) but The Ghost’s Child is also a narrative of resilience and recovery. A coming-of-age tale that is both magical and moving – and which deserves to be considered an Australian classic.

Hartnett has never been one to shy away from controversial subject matter. In fact, she has openly embraced it: Wilful Blue (1994) tackled youth suicide, while Sleeping Dogs (1995), which is probably the novel she is most famous for, revolves around brother/sister incest.

Interestingly, Hartnett’s work has often been called “bleak” – but The Ghost’s Child is a tender meditation on the life choices and experiences that mould and influence the people we eventually become.

Magic in the everyday world

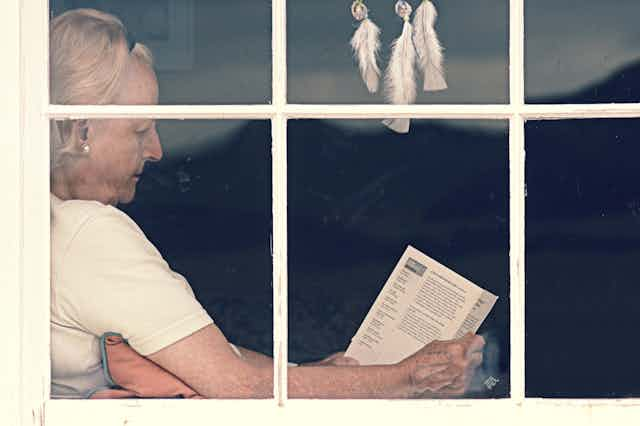

The novel opens when Matilda, an old lady of 75, comes home from walking her dog to find a young boy sitting in her living room. She welcomes him in and offers him tea and biscuits, and is infinitely patient when he begins to question her about her life. In response to his suggestion that the choices she has made have left her with only a dog for company, she refuses to regard herself with pity, asserting simply that:

The view from the mountain top is good, but you can only see clearly the road you took to reach where you stand. The other roads – the paths you might have taken, but didn’t – are all around you too, but they are ghost roads, ghost journeys, ghost lives, and they are always hidden by cloud.

As the reference to ghosts here might imply, the great charm of this novel lies in its deft handling of magical realism. Matilda’s awkward adolescence and increasing alienation from her parents are familiar to any reader of realist young adult fiction – but what The Ghost’s Child seems to suggest is that magic is inherent in the everyday world.

Matilda’s unhappy childhood is made bearable through her friendship with a nargun, a half-stone beast from the “Dreamtime” who acts as her protector and confidante. When she despairs that her parents will never understand her, her father whisks her away on a travel adventure – the purpose of which is to unravel a riddle: what is the world’s most beautiful thing?

At the end of the journey he hands Matilda a mirror, telling her that it will reveal what is most precious in life to him.

Fantasy and loss

But the most magical moment of Matilda’s life is when she meets Feather, a wild bird-man whom she loves with all her heart. Although Feather does his best to return her love, their relationship is doomed to failure.

Thus the “magic” in Matilda’s account of her life does not belong to an “otherworld” of dragons and wizards. It is the wonder and enchantment that turns everyday occurrences into moments of great emotion and poignancy. Hartnett’s ability to render commonplace human experiences - such as marriage break-down and the loss of an unborn child - in such a startlingly poetic and original manner is what makes this novel a joy to read.

The fantastic elements of The Ghost’s Child are more than just aspects of plot, however. They are also a product of two carefully-rendered strategies.

The first is the way in which the narrative is structured. Matilda tells her life story to the young boy, who occasionally interjects – which also allows the older Matilda to reflect on her younger self. This technique continually returns the reader’s attention to the boy and his relationship with Matilda.

The second is the novel’s concealment of why this story-telling process might be significant. The young boy is, of course, Matilda’s unborn son, a ghost who comes to her side as she is dying in order to accompany her to the afterlife.

Her relationship with him is the magical element around which the narrative is shaped, particularly since he is the audience for whom she reconstructs her life’s experiences as a story worth telling. As the novel’s title suggests, Matilda’s own status as “real” or “ghost” is blurred because of her interactions with this boy. Forever separated from him in life, it is death which reunites them – and on the journey towards death it is the child who has come to comfort the mother.

The tender spirituality of this idea encapsulates Hartnett’s capacity to find great beauty in suffering and to offer a perspective of human existence that is both open-hearted and affirming.

Suffering and survival

Although Matilda has suffered throughout her life, it does not define her existence. I prefer to read Matilda’s story as one of survival, and to see her as a character who successfully overcomes adversity.

Other critics, such as Michelle Preston, would perhaps disagree – as she views the novel as a study of melancholy and madness, “an anti-bildungsroman of chances lost”.

To interpret Matilda’s identity and life in this way, however, is to deny her character any sense of personal fulfilment or autonomy. Perhaps more disturbingly, it suggests that a woman who remains childless and unmarried throughout her life is ipso facto a tragedy. The Ghost’s Child may deal with loss and grief, but it is surely not a tragedy.

As Matilda creates the narrative of her experiences, she self-authors a version of her life (and also her own identity) that is replete with enchantment and wonder. Her death is emblematic of her capacity to view the world around her as magical, and as she accompanies her son on this final journey, she looks back upon her life with pride and happiness:

She had witnessed the world’s most beautiful things, and allowed herself to grow old and unlovely. She had felt the heat of a leviathan’s roar, and the warmth within a cat’s paw. She had conversed with the wind and had wiped soldier’s tears. She had made people see, she’s seen herself in the sea. Butterflies had landed on her wrists, she had planted trees. She had loved, and let love go. So she smiled.

Matilda is an independent and feisty feminist heroine if ever there was one – and this sweet yet powerfully symbolic story is a perfect fairy tale for the modern era. If only all books for young adults contained such endearing female role models.

Are you an academic or researcher? Is there an Australian book or piece of writing – fiction or non-fiction, contemporary or historical – you would like to make the case for? Contact the Arts + Culture editor with your idea.

Further reading:

The case for Kim Scott’s That Deadman Dance

The Case for John Bryson’s Evil Angels

The case for Henry Handel Richardson’s The Getting of Wisdom

The case for Sheilas, Wogs and Poofters by Johnny Warren