Imagine, for a moment, the technology of 2017 had existed on Jan. 11, 1964 – the day Luther Terry, surgeon general of the United States, released “Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the United States.”

What would be some likely scenarios?

The social media noise machine explodes; conservative websites immediately paint the report as a nanny-government attack on personal freedom and masculinity; the report’s findings are hit with a flood of satirical memes, outraged Facebook posts, attack videos and click-bait fake news stories; Big Tobacco’s publicity machine begins pumping out disinformation via both popular social media and pseudoscientific predatory journals willing to print anything for a price; Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater characterizes “Smoking and Health” as a “communist-inspired hoax.”

Eventually, the Johnson administration distances itself from the surgeon general’s controversial report.

Of course none of the above actually occurred. While Big Tobacco spent decades doing all that it could to muddy the waters on the health impacts of smoking, in the end scientific fact triumphed over corporate fiction.

Today, thanks to responsible science and the public policies it inspired, only 15 percent of adults in the United States smoke, down from 42.4 percent in 1965.

One might ask: Would it have been possible to achieve this remarkable public health victory had today’s social media environment of fake news and information echo chambers existed in 1964?

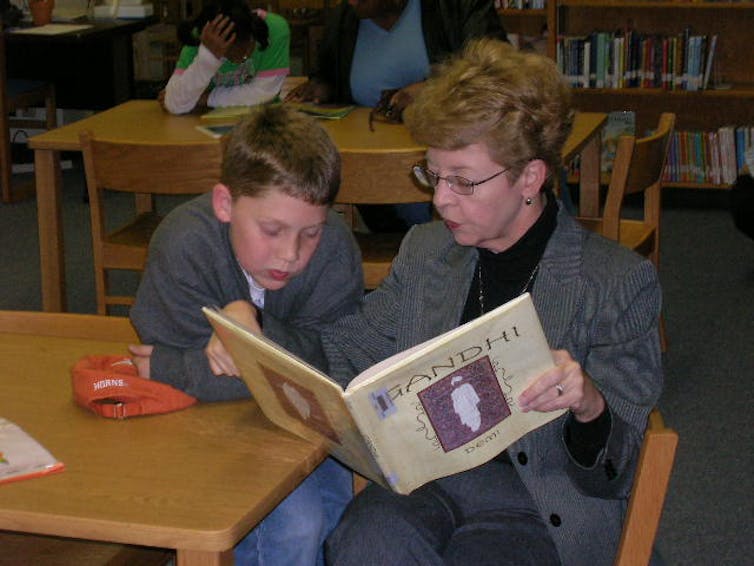

Maybe not. As a long-time academic librarian, I have spent a good part of my career teaching college students to think critically about information. And the fact is that I watch many of them struggle with the challenges of discovering, internalizing, evaluating and applying credible information. For me, the recent spate of stories about large segments of the population falling for fake news stories was no surprise.

Making sense of information is hard, maybe increasingly so in today’s world. So what role have academic libraries played in helping people make sense of world bursting at the seams with information?

History of information literacy

Since the 19th century, academic librarians have been actively engaged in teaching students how to negotiate increasingly complex information environments.

Evidence exists of library instruction dating back to the 1820s at Harvard University. Courses on using libraries emerged at a number of colleges and universities after the Civil War. Until well into the 20th century, however, academic librarians largely gave library building tours, and their instruction was aimed at mastery of the local card catalog.

Beginning in the 1960s, academic librarians experienced a broadening of their role in instruction. This broadening was inspired by a number of factors: increases in the sheer size of academic library collections; the emergence of such technologies as microfilm, photocopiers and even classroom projection; and such educational trends as the introduction of new majors and emphasis on self-directed learning.

The new instructional role of academic librarians was notably reflected in the coining of the phrase “information literacy” in 1974 by Paul G. Zurkowski, then president of the Information Industry Association.

Rather than being limited to locating items in a given library, information literacy recognized that students needed to be equipped with skills required to identify, organize and cite information. More than that, it focused on the ability to critically evaluate the credibility and appropriateness of information sources.

Changes in a complex world

In today’s digital world, information literacy is a far more complex subject than it was when the phrase was coined. Back then, the universe of credible academic information was analog and (for better or worse) handpicked by librarians and faculty.

Students’ information hunting grounds was effectively limited to the campus library, and information literacy amounted to mastering a handful of relatively straightforward skills, such as using periodical indexes and library catalogs, understanding the difference between primary and secondary sources of information, and distinguishing between popular and scholarly books and journals.

Today, the situation is far more nuanced. And not just because of the hyperpartisan noise of social media.

Thirty or 40 years ago, a student writing a research paper on the topic of acid rain might have needed to decide whether an article from a scientific journal like Nature was a more appropriate source than an article from a popular magazine like Time.

Today’s students, however, must know how to distinguish between articles published by genuine scholarly journals and those churned out by look-alike predatory and fake journals that falsely claim to be scholarly and peer-reviewed.

This is a far trickier proposition.

Further complicating the situation is the relativism of the postmodern philosophy underpinning much of postmodern scholarly thinking. Postmodernism rejects the notion that concepts such as truth and beauty exist as absolutes that can be revealed through the work of creative “authorities” (authors, painters, composers, philosophers, etc.).

While postmodernism has had positive effects, it has simultaneously undermined the concept of authority. If, as postmodernist philosophy contends, truth is constructed rather than given, what gives anyone the right to say one source of information is credible and another is not?

Further complicating the situation are serious questions surrounding the legitimacy of mainstream scholarly communication. In addition to predatory and fake journals, recent scandals include researchers faking results, fraudulent peer review and the barriers to conducting and publishing replication studies that seek to either verify or disprove earlier studies.

So, what’s the future?

In such an environment, how is a librarian or faculty member supposed to respond to a bright student who sincerely asks, “How can you say that a blog post attacking GMO food is less credible than some journal article supporting the safety of GMO food? What if the journal article’s research results were faked? Have the results been replicated? At the end of the day, aren’t facts a matter of context?”

In recognition of a dynamic and often unpredictable information landscape and a rapidly changing higher education environment in which students are often creators of new knowledge rather than just consumers of information, the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) launched its Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education, the first revision to the ACRL’s standards for information literacy in over 15 years.

The framework recognizes that information literacy is too nuanced to be conceived of as a treasure hunt in which information resources neatly divide into binary categories of “good” and “bad.”

Notably, the first of the framework’s six subsections is titled “Authority Is Constructed and Contextual” and calls for librarians to approach the notions of authority and credibility as dependent on the context in which the information is used rather than as absolutes.

This new approach asks students to put in the time and effort required to determine the credibility and appropriateness of each information source for the use to which they intend to put it.

For students this is far more challenging than either a) simply accepting authority without question or b) rejecting all authority as an anachronism in a post-truth world. Formally adopted in June 2016, the framework represents a way forward for information literacy.

While I approve of the direction taken by the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education, I do not see it as the ultimate solution to the information literacy challenge. Real progress in information literacy will require librarians, faculty and administrators working together.

Indeed, it will require higher education, as well as secondary and primary education, to make information literacy a priority across the curriculum. Without such concerted effort, a likely outcome could be a future of election results and public policies based on whatever information – credible or not – bubbles to the top of the social media noise machine.