Before 2010, we would have been forgiven for thinking that British elections were simple. Two main parties would compete for the nation’s votes, trying to win enough seats to achieve a parliamentary majority. Voters would wake up on the morning after the election and know who the next prime minister was going to be. They would appear at the door of Number 10 before the day was out. Job done.

With one hung parliament already under its belt this century, the UK is perhaps a bit more comfortable with the idea of coalition government this time. But there is a big difference between 2015 and 2010, when the two parties both sought to woo the Liberal Democrats for a coalition. In 2015, the parliamentary arithmetic will almost certainly be a lot more complicated.

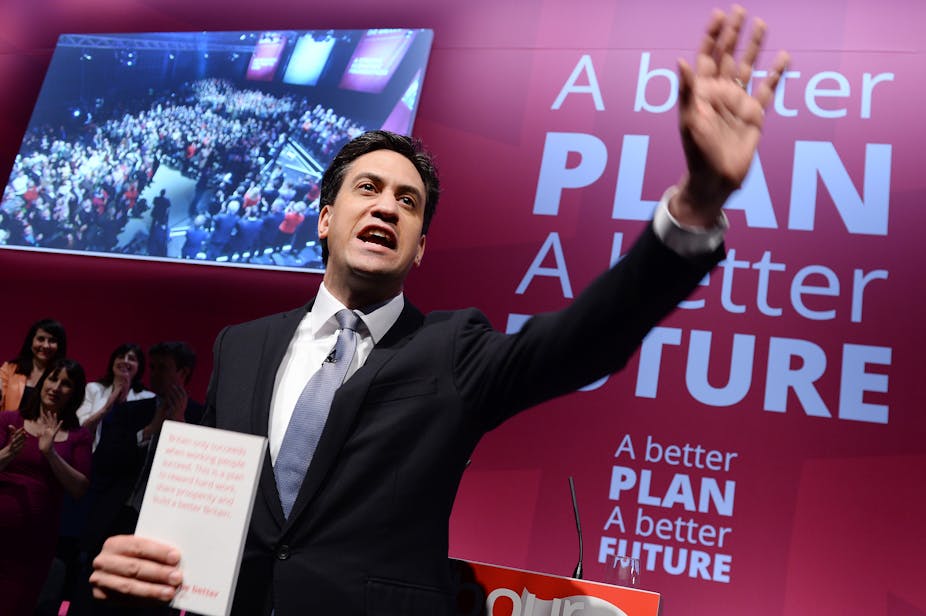

With a kaleidoscope of smaller parties holding a far greater number of seats than before, it will be much harder for either David Cameron or Ed Miliband to achieve a parliamentary majority.

The magic number they are said to need is often slightly different, as it depends on whether you include Sinn Fein MPs who do not take their seats in the House of Commons. So while the BBC puts it at 326 seats, others say it is 323. Either way, the magic number seems out of reach for any party on its own.

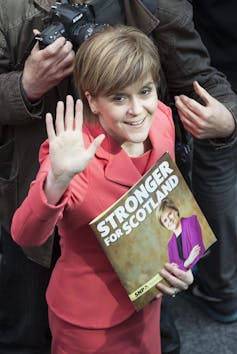

For most of the long campaign, Labour seemed to have the upper hand here. The SNP seemed like a credible option, as did the Liberal Democrats. But Miliband has ruled out both a formal coalition with Nicola Sturgeon’s SNP and has now even said he won’t team up with the party on a less formal confidence-and-supply agreement. This means his options are much more narrow.

Doing the sums

Saying that Nick Clegg’s yellow army has fallen under the radar in this election campaign would be something of an understatement. Thwarted in his attempts to take part in the challengers’ debate, the Liberal Democrat leader has failed to pull off the TV debate coup which propelled his party into the spotlight in the 2010 campaign.

His party has been careful to cast itself as the best possible option for a coalition partner. But the Liberal Democrats’ 23% share of the vote will plummet, with the BBC predicting a share of just 9% and other forecasting tools predicting the party will lose more than half of its 57 seats.

Estimates range somewhere between 18 and 26 seats. Either way, the Lib Dems alone wouldn’t be enough to help Labour get to the finishing line and they would need to look elsewhere too. And this is complicated by Clegg ruling out a coalition with any party who is also planning to work with either the SNP or UKIP.

It would leave the Greens and Plaid Cymru, but with both parties very unlikely to gain more than a handful of seats, neither would be enough to give an absolute majority.

This leaves us with the Northern Irish parties. Although largely ignored in the campaign so far, the Social Democratic and Labour Party could prove a crucial feature of negotiations. Miliband may need the handful of seats held by the SLDP, but once again has already ruled out a formal coalition.

The unionist DUP and UUP are likely to have a greater number of MPs but are more believable as partners for the Conservatives – even if the DUP is signalling its interest in a deal with either party.

Of course, much of what the leaders are saying right now may just be tactical posturing. Both Cameron and Miliband would much rather have an outright majority and don’t want to be seen spending too much time discussing the nitty gritty of coalition deals.

Nor does Sturgeon seem too bothered by Miliband’s current position on governing with her party. She seems happy to push the Labour leader to rethink his plans later on.

The Tories have made a possible Labour-SNP coalition a large plank of their election campaign strategy, pushing the line that it would be chaos, but in reality, any coalition will be more chaotic this time around. Or at the very least, the negotiations will be.

Miliband’s game

Miliband’s bold decision to rule out even a confidence and supply with the SNP may be a sign of something else. The Labour campaign has noticeably stepped up a gear in the last week or so and Miliband’s fortunes seem to be on the up and this momentum may well increase further.

A last minute surge in support for Labour may close the gap enough to make coalition negotiations a bit less chaotic. There is also the seemingly outlandish idea that perhaps Miliband is so confident now that he is daring to dream of achieving a very small Labour majority. Perhaps he knows something that the rest of us don’t. Or perhaps he should sit down with a calculator.