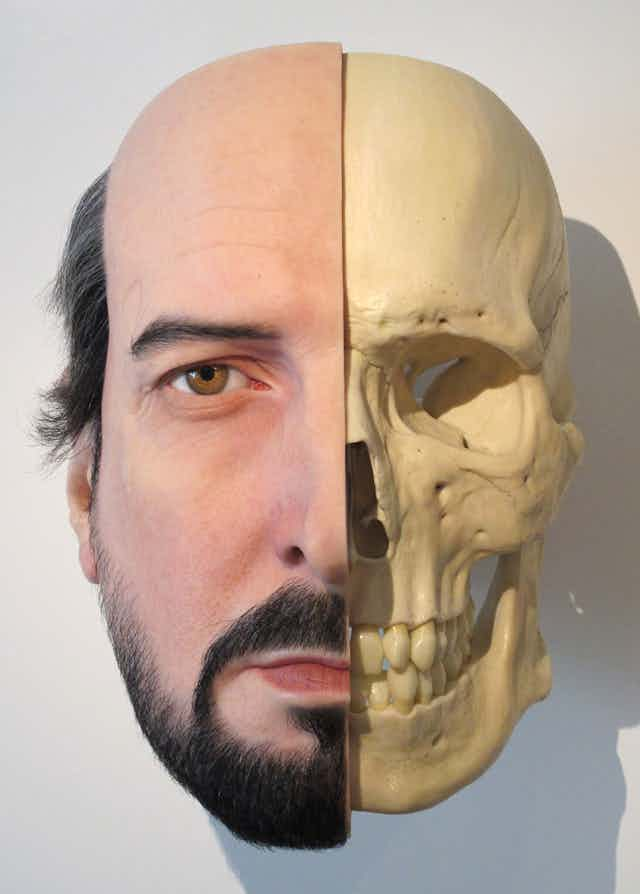

With little time to bask in the critical success of current shows at the NGA (Hyper Real) and Art Gallery of Ballarat (Romancing the Skull), Melbourne artist Sam Jinks is back in his Coburg studio, surrounded by heads and moulds of body parts. The clay faces in front of him will be cast in silicone to form part of the skin of a new generation of life-like robots that will, Jinks believes, inevitably end up indistinguishable from humans.

For the past two years, Jinks has been involved in an ongoing collaboration with a robotics engineer based in the US to provide the “skin” for humanoid robots. As he notes,

we seem to be on the cusp of having the engineering and process capabilities to create robots that not only perform amazing feats, but can imitate convincingly human movement and speech.

The choice to involve an artist rather than a special effects technician is both unusual and revealing. A primary reason for this is aesthetic – someone will be making the skins for these robots and the inclusion of a sculptor avoids “clunkiness”, introduces subtlety, and helps to create a robot that could be mistaken for human, emerging on the other side of the uncanny valley.

However, the inclusion of artists and other people from the creative and humanities fields in the AI discourse is vital for other reasons. The quest to create a robot that is indistinguishable from humans has become all-consuming for many scientists, engineers and technicians.

In recent attempts to make robots that look human, such as Sophia, Han, Erica, and Jia Jia, the latest technology is able to capture micro-movements of the face including blinks and frowns. While this is an interesting intellectual exercise, there will be profound implications when we can no longer distinguish between robot and human. The consequences could potentially be both beneficial and catastrophic.

Robots could be used to free up human labour from “mindless” tasks, leaving humans to engage in “purposeful” work. They are particularly suited to helping with tasks related to quality of life, health, education, and security. Robots could have therapeutic uses and provide carers and companions for the elderly, the disabled, the isolated and the lonely. The American Psychological society cites loneliness and isolation as potentially a greater public health hazard than obesity. Jinks foresees a role for “empathetic and approachable companion robots” in aged-care facilities and for people suffering from social isolation.

On the other side of the equation, autonomous robots could potentially cause harm (any robot capable of lifting paralysed individuals into bed could also potentially crush them). They could malfunction or be used to psychologically exploit vulnerable people, reinforce social isolation and become objects of addiction.

Jinks comes from a science-oriented family and has the scientist’s drive and curiosity to see how far something can be taken. However, this is tempered by an artist’s sensibilities and concerns with profound and universal truths. His art practice is religiously inspired without being religious, a quest for insight into something deeper about the human condition. Rather than an all-consuming drive toward a specific end, Jinks sees art as revolving around questions, posing an idea and then exploring its implications.

His contribution to the discourse is important. For example, in an industry in which the majority of robots are presented as very attractive but servile young women, Jinks points out that the gender and age of the robot persona are a matter for careful consideration. He is currently working on a slightly androgynous face for his first robot collaboration.

There are a myriad of moral and ethical concerns to be navigated in the AI future. Indeed the legal status of autonomous robots has yet to be worked out. Are they people in the sense that corporations can be people for legal purposes or do we need to invent the new category of “electronic person”? Do self-learning robots have legal responsibilities? Just last week, Saudi Arabia granted citizenship to Sophia, Hanson Robotics’ lifelike humanoid.

Do robots have moral and legal rights – the right not to be tortured, the right to consent to sex (can you consent to your own programming)? As Jinks points out, if robots are indistinguishable from humans but have restrictions placed upon their behaviour and movement, “aren’t we legislating discrimination?”

What about the humans with whom robots interact? Should there be a legal requirement (as in the TV show Humans) to install a physical feature that allows people to know that they are interacting with a robot?

One of the most intensely debated topics is human-robot relationships. With US military personnel already demonstrating attachment to their bomb disposal robots, Japanese empty-nesters treating hard-shelled Pepper (who spontaneously farts!) as a surrogate child, and robot celebrants officiating at Japanese marriages, robophilia is already here.

Some of the current soft robotics technology has drawn from the increasingly realistic sex doll industry. Here the emphasis is on tactility and even haptics.

Researchers can add pheromone and other scent markers to robots. Indeed, some roboticists are specifically examining the design features of a robot that may lead to the formation of mutual love between it and a human.

Futurist Ian Pearson predicts that by 2025, women will choose robots instead of men, and by 2050, everyone will prefer robots.

The habitually questing and questioning approach taken by artists like Jinks, coupled with a concern with universal themes and the spiritual dimensions of the human condition, are vital in an age of terrific and terrifying possibilities.