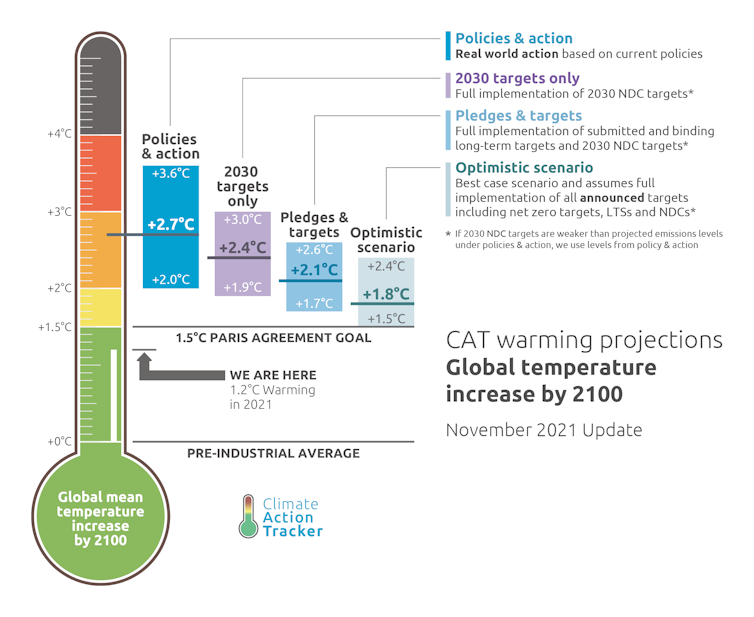

A new, grim projection, released overnight by Climate Action Tracker, has dashed the cautious optimism following last week’s commitments at the UN climate talks in Glasgow. It found the world is still headed for 2.1°C of warming this century, even if all pledges are met.

Similar new analysis from Climate Analytics suggests if global warming is to be limited to 1.5°C, an enormous ambition gap remains for this decade.

Last week, national leaders shared their plans to cut carbon pollution and to transition to a net-zero emissions economy. Some countries made much more ambitious commitments than others. The UK for example, as summit hosts, pledged to cut emissions by 68% this decade, while Australia – a clear laggard among developed countries – refused to strengthen the target it set in 2015 to cut emissions by 26-28% by 2030.

Taken together, national announcements clarify that the world has made some progress since the 2015 Paris climate summit, but not nearly enough to avoid climate catastrophe. So what needs to happen in the final days of frantic negotiations at COP26 to close the ambition gap?

Global ambition in this decisive decade

While most world leaders have headed home, negotiators remain locked in late night talks aimed at securing a “Glasgow Package”, including a final political outcome that will keep the goals of the Paris Agreement in reach. Their discussions are now focused on achieving a political outcome that will accelerate climate action this decade.

The 2015 Paris Agreement requires countries to set new and more ambitious targets to reduce emissions every five years, and national pledges aren’t due again until 2025. But if the world is to keep the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C in reach, countries will need to increase ambition before then.

More than 100 countries are calling for strengthened ratchet mechanisms to be established in Glasgow, which could require countries like Australia to set a new 2030 target as soon as next year. These proposals have support from major powers, including the United States, but achieving consensus for an ambitious Glasgow package will be a tough ask.

The good news is countries have committed to greater climate action than they did in 2015. This provides hope that the Paris Agreement – which requires stronger commitments over time – is working.

Last week, projections from the International Energy Agency suggested that, if they are fully funded and implemented, Glasgow commitments give the world a 50% chance to limit warming to 1.8°C this century.

But the bad news? This is a big “if”. As it is, Earth is still on track for catastrophic warming. Emissions are projected to rebound strongly in 2021 (after an unprecedented drop in 2020 because of the global pandemic).

Indeed, alongside the sobering findings overnight that we’re still on track for at least 2.1°C global warming, the UN Environment Programme updated its Emissions Gap Report. Taking last week’s pledges into account, it found we’re on track to reduce global emissions by just 8% by 2030, falling well short of the 55% reduction needed to keep global warming to below 1.5°C.

Limiting warming to 1.5°C this century is key to avoiding the worst impacts of climate change, and is a matter of survival for some Pacific island nations.

In Glasgow, groupings of countries at the frontline of climate change – including 55 members of the Climate Vulnerable Forum, 48 Least Developed Countries, and 39 members of the Alliance of Small Island States – have put forward proposals that would require accelerated emissions cuts this decade.

These proposals have won support from key developed nations, including the United States, as part of the High Ambition Coalition – a grouping of countries that unites developed and developing nations which have traditionally not acted in concert.

This coalition was crucial to securing the 2015 Paris Agreement. Last week, it stressed the need to halve global emissions by 2030, and called on parties to deliver more ambitious national commitments well before COP27 “in line with a 1.5°C trajectory”.

This provides renewed hope Glasgow will deliver a political outcome that will require countries to ratchet up short-term climate action.

Finding a ‘landing zone’ for a Glasgow deal

The COP26 presidency has tasked the nations of Grenada and Denmark with finding a landing zone for a Glasgow decision that would “keep 1.5°C alive”. In October, Denmark released a summary of consultations they held with country negotiators to that point.

It provided options including:

a requirement for countries that have not yet submitted enhanced targets to do so in 2022

an annual review of pre-2030 ambition

a leaders-level event to consider 2030 ambition.

All these options made it to an early draft of the Glasgow final decision text released at the weekend, and a new draft is expected on Wednesday morning (Glasgow time).

However, significant differences between countries remain, and negotiators will now try to hammer out a final political outcome. Saudi Arabia, for example, has already tried to head off an ambitious commitment to new action before 2030.

The Australian government might have been cheering Saudi Arabia from the sidelines. Australia is the only advanced economy that didn’t bring a strengthened 2030 target to Glasgow. An ambitious political statement in the COP26 decision text could require the federal government to set new 2030 targets – and devise policy to meet them – as soon as next year.

Reaching consensus

The UN climate talks are built on consensus among 190-odd countries. Achieving meaningful outcomes is a diplomatic balancing act built on trust among negotiating parties.

Central to building trust is a commitment by wealthy nations to provide climate finance, to help developing countries deal with the impacts of climate change and to transition to low-emissions development.

More than a decade ago, wealthy nations promised the developing world they would provide US$100 billion per year by 2020. So far they have failed to deliver on this promise.

However, US climate envoy John Kerry says rich nations will meet the goal by 2022 (and exceed it over the 2020-2025 period).

Wary of broken promises, developing countries are looking for renewed commitments on climate finance, especially for the period after 2025. Countries most clearly in the firing line of climate impacts are also pressing for finance to compensate for unavoidable loss and damage.

Progress in the UN climate talks, both at COP26 and beyond, may involve a “grand bargain” encompassing new promises on climate finance from wealthy countries, and new commitments to reduce emissions from both developed and developing countries.

It is no overstatement to say the fate of our planet depends on the next few days of complex multilateral diplomacy in Glasgow.

This story is part of The Conversation’s coverage on COP26, the Glasgow climate conference, by experts from around the world.

Amid a rising tide of climate news and stories, The Conversation is here to clear the air and make sure you get information you can trust. More.