Steve McQueen’s success at the Oscars has prompted much talk of the connection between art and film, and his ability to “straddle these two worlds”. But why is it so surprising that these worlds must be straddled?

Art and film are usually seen as separate professional paths. But artists have always been into film – the film industry is only starting to sit up and take note now.

And here at Goldsmiths, where McQueen studied, along with most other universities, film is taught in separate departments – in both the Department of Art and the Department of Media and Communications. It follows that it is a different sort of film that is taught in each one. But why are they perceived to be so divorced from one another?

I am a filmmaker and artist myself. Within the art world of course, film has not been viewed as such a distant entity that warrants “straddling”. This is a view that has only existed from the film world. But increasingly, this divided Berlin is experiencing its wall-tumbling moment.

Most artists who work with moving image don’t see themselves as filmmakers. But from the very beginning of film, artists were fascinated by the potential it had as an art form. Sometimes film was used as an add-on to an artist’s main practice, such as in the case of the Surrealists, who loved the spectral and unexpected possibilities of superimposition, editing, and theatrics.

Then from the 60s up to the 90s artists began to explore film as a medium and material in its own right, as a form of art. Artists created their own cinemas, workshops and distribution networks – a film world on the margins of the gallery and the industrial model of filmmaking.

Then in the Young British Artists explosion of the 90s we saw artist/filmmakers migrating to the gallery and into the arms of art audiences. The art world was now attuned to moving image as an art form.

But it’s not quite the same from the other perspective. The film world is still quite suspicious of art as film, film as art, artists’ films and other varieties of this relationship.

It’s true that when artists made forays into industrial or mainstream film or documentary, the results could be disastrous, stilted and lacking in fluidity. So perhaps the film industry looks at artists as amateurs, playing at making films but not making “real” ones, messing around and experimenting without enough skills in the craft or language of film.

But gallery artists like Steve McQueen, Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard are standing their ground and proving that they can make great filmmakers on their own terms, and on the terms of the mainstream itself.

Prestigious showcases such as Locarno and the Venice and the Rotterdam film festivals have been celebrating the work of artist filmmakers now for several years, not to mention the recent Oscars. These previously exclusive places are now showing artist-led films that depart from standard narrative. Change is in the air, and discussion and debate are beginning.

Many critical spaces such as the CPH:DOX Cophenhagen Documentary Film Festival are now discussing the symbiotic relationship between film and art as well as considering the potentials of funding crossovers. The television and documentary markets for example are particularly active in this field.

So when we ask “why do artists make great filmmakers?” what we really need to think about is what has changed. Artists have always made great filmmakers, but it is the film world that is opening up and taking notice of their skills and taking them seriously as producers of films which can create new audiences.

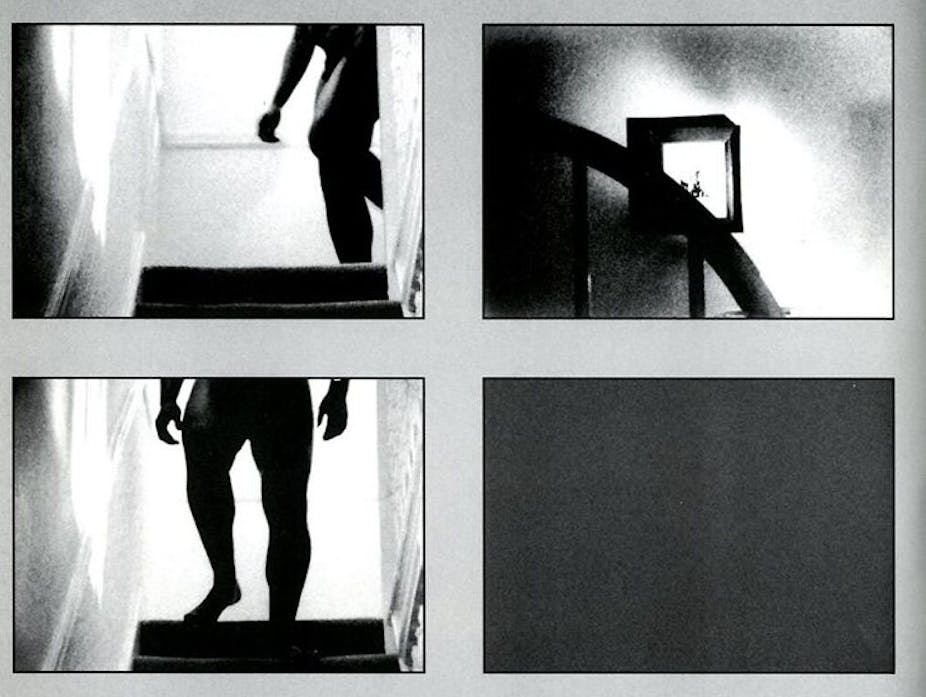

Artists are risk-takers. Their artistic decisions are visual-led, rather than being drama-led. This is arguably what led to the success of 12 Years a Slave, a film many consider to be the first to look slavery straight on. It did not cut things up into a more standardised editing thought to be more accessible to a mainstream audience.

Artists are trained in a culture of experimentation – they are taught to not respect boundaries. This means that they are not constrained by technical dos and don’ts. They are aware of the codes of cinema but choose to tackle them head on or reinvent them to their own purposes. They tend to have a healthy distance to the material and existing forms.

These previously held disadvantages are becoming assets in a visually voracious culture where the success of Tate Modern and other galleries has created a public more open to art.

Many artists have experimented with installations and other ways of experiencing the spectacle of cinema and this gives them an insight into forms of visual manipulation. They can use these skills to induct audiences into new ways of experiencing images and sound. This refreshes the possibilities for cinema.

Most of all, artists have begun to circulate within the celebrity system of the art world since the YBAs began to receive popular mass media attention. And some, like Sam Taylor Johnson, are capable of commanding or attracting the large amount of money needed for feature productions, from both the super consumer global art market place, and in the film markets.

Previously, many artists wanting to branch out found themselves forming music groups and joining the music industry. Now they are sticking to what they know: the visual image, and taking this knowledge into the film world. It’s an ongoing conversation between the two, but what is important is that the film world, for the first time, is sitting up and taking notice, and this promises exciting things for the future in film.