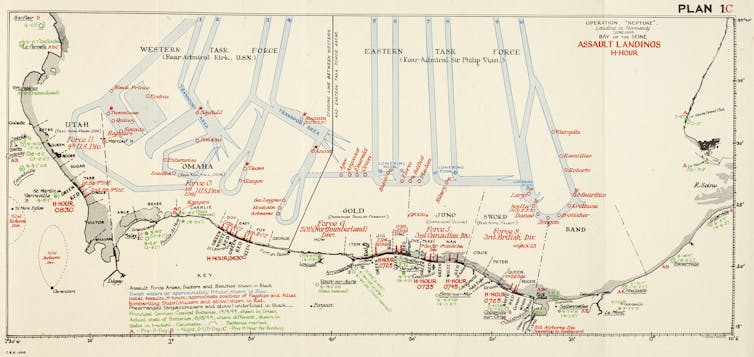

Among the many Allied military units storming the Normandy coast on June 6, 1944, was the 16th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. Army’s 1st Infantry Division. Its members faced a particularly daunting task: As part of the first wave of the largest amphibious assault in history, the regiment was assigned to clear the Omaha Beach landing sectors code-named “Easy Red” and “Fox Green.”

This was no ordinary assault. Omaha would become the most deadly of the five D-Day landing beaches, as the U.S., U.K. and allied nations attacked Nazi-occupied France in World War II. The liberation of Europe hung in the balance.

As the regiment’s members sat down to a steak dinner the night before the invasion, they no doubt thought about the legacy of their unit. As a military and oral historian, I researched this particular regiment’s service in Vietnam and became fascinated by its earlier history as well.

The 16th Infantry had fought in the Indian Wars, chased Mexican revolutionary leader Pancho Villa, fought in the Battle of San Juan Hill that made Theodore Roosevelt a national hero, and saluted Revolutionary War commander Marquis de Lafayette at his tomb in Paris as the U.S. entered World War I. By D-Day, the regiment had already participated in the World War II invasions of North Africa and Italy in 1942 and 1943.

The regiment was so well thought of by the American public that when author F. Scott Fitzgerald created his infamous antihero Jay Gatsby in 1925’s “The Great Gatsby,” the title character was described as a veteran of the 16th Infantry.

That steak dinner the night before D-Day, recalled Charles Hangsterfer, then a captain in the 16th Regiment, was “just like they would give a convicted murderer his last meal on the evening of his execution.”

A dangerous attack

The invasion plan had called for heavy bombardment from warships and airplanes to weaken the German defenses, and for amphibious tanks – which could travel through shallow water and on land – to support the infantry as they hit the beaches.

But as dawn broke on June 6, 1944, bad weather intervened. Low clouds meant the bombardments largely missed their targets. Rough seas – swells between 3 and 6 feet, and 25 mph winds – swamped most of the tanks.

The troops themselves were seasick from the pitching and rolling of the small boats they were using to get to the beaches from larger ships offshore, and learned upon landing that their arrival was later than expected, and often far from its intended destination.

Ted Lombarski, a sergeant in the 16th’s F Company, recalled:

“We were the first wave to hit the beach, Companies E and F of the 16th Infantry. Almost all the tanks that had gone in before us were sunk. The tank crews had a rough time, and so did the navy personnel who drove us in. … As we went in, we knew that the air force had dropped their bombs too far inland and that the navy shelling had done likewise. The first wave went through hell that day.”

As they approached Omaha Beach, the men of the 16th Infantry Regiment were met with a wall of enemy fire. The bullets and shrapnel made the ocean appear to be boiling, according to an oral history of the regiment.

The landing craft didn’t go as far toward the shore as the soldiers had hoped, Capt. Everett Booth recalled:

“They didn’t get us very close to the beach, I’ll tell you. … We ran off into water about chest high. We were met with machine-gun bullets hitting all over the water. … The enemy was riddling the beach with machine-gun fire.”

And Lombarski recounted:

“Being in that first wave was like committing suicide. If you exposed yourself, you were dead.”

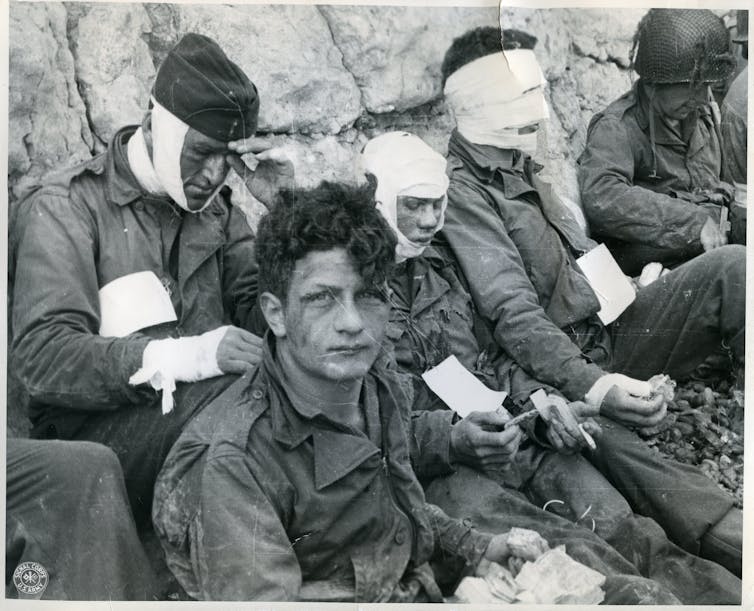

Burdened with weapons, ammunition, equipment and heavy packs, many soldiers were overcome by the sea and drowned. Those who made it to the beach found themselves up against the 352nd Infantry Division of the Nazi army, a unit with significant combat experience against the Soviets in Eastern Europe.

Heavy casualties

Despite the heavy losses and powerful German defense, as the day wore on it became clear that the 16th Infantry Regiment had secured a foothold on Omaha Beach. The soldiers fought through concrete and wooden obstacles the Nazis had placed on the beach, destroyed machine-gun emplacements and cleared enemy troops from key locations one by one.

There was no shortage of heroes that day – there were almost too many to count. Two of the four Congressional Medals of Honor awarded for actions on June 6 went to men of the 16th. At the beginning of the morning, 1st Lt. Jimmie Montieth exposed himself to enemy fire numerous times, including leading tanks through a minefield. He led his troops off the beach, organizing the various companies to hold the enemy positions gained by the 16th. Just hours later, he was killed in a German counterattack.

Technician 5th Class John Pinder Jr., though wounded multiple times, made several trips into the fire-riddled surf to collect communications equipment. He helped establish radio contact with his commanders offshore before succumbing to his wounds.

They were among the nearly 1,000 casualties of the 16th Infantry killed, wounded or missing on D-Day. Despite these heavy losses – roughly one-third of the unit’s troops – the regiment’s relentless assault began to break through the German defenses, allowing the follow-up forces to push farther and farther inland. Victory was not guaranteed, but it was at hand.

Their courage and sacrifice were honored in a July 2, 1944, ceremony at a chateau 15 miles inland from the beach. The regiment had earned a Presidential Unit Citation for its role in the invasion. During the presentation, Allied commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower told the regiment:

“I’m not going to make a long speech, but this simple little ceremony gives me an opportunity to come over here and, through you, say thanks. You are one of the finest regiments in our army. I know your record from the day you landed in North Africa and through Sicily. I am beginning to think that your regiment is a sort of Praetorian Guard, which goes along with me and gives me luck.”