A long-term plan to cut the company tax rate from 30% to 25% is the centrepiece of the Coalition’s economic plan for jobs and growth. The Coalition maintains the change will boost GDP by more than 1% in the long-term, at a budgetary cost of $48.2 billion over the next 10 years.

But the very Treasury research papers relied on by the Coalition tell a more modest story than the headlines. Using these papers, we show that the net benefit to Australians in the real world will be only about half of the headline benefit, and it will be a long time before we are any better off at all.

The short story

The Government has made two claims about the economic impacts of its plan to cut the company tax rate.

On Budget night Treasurer Scott Morrison said that the tax cuts would:

“… mean higher living standards for Australians and an expected permanent increase in the size of the economy of just over one percent in the long term.”

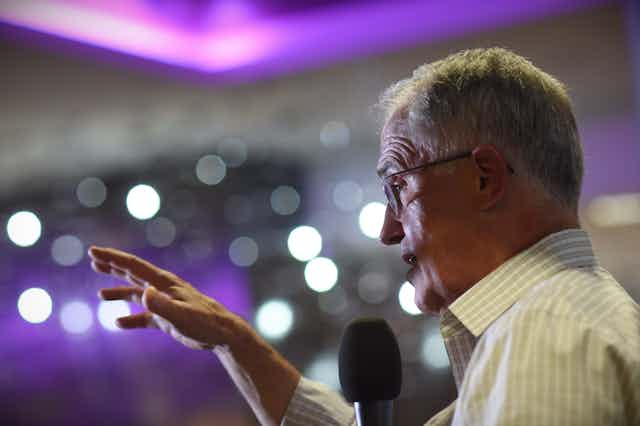

Later last week, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said:

“The Treasury estimated last year…that for every dollar of company tax cut, there was four dollars of additional value created in the overall economy.”

Sound in theory, but there’s a back story

In theory, cutting the company tax rate boosts the economy in the long term. All taxes distort choices, and thereby drag on economic activity. Taxes on capital often have especially large economic costs because they discourage investment, which is mobile across borders. By some estimates, roughly half of the economic costs of Australian company tax ultimately fall on workers, as lower company profitability leads to lower investment, and therefore lower wages and higher unemployment.

But while the theoretical argument for company tax cuts is straightforward, the real story is more complicated.

The twist: a tax cut for foreign investors

The twist in the tale comes from Australia’s system of dividend imputation, or franking credits. The effect of this system is to make the company tax rate for Australian resident shareholders effectively close to zero. In nearly every other country, company profits are taxed twice: companies pay tax, and then individuals also pay income tax on the dividends, albeit often at a discount to full rates of personal income tax.

But in Australia, the shares of Australian residents in company profits are effectively only taxed once. Investors get franking credits for whatever tax a company has paid, and these credits reduce their personal income tax. Consequently, for Australian investors, the company tax rate doesn’t matter much: they effectively pay tax on corporate profits at their personal rate of income tax.

As a result, although Australia has a relatively high headline corporate tax rate compared to our peers, in practice the comparable tax rate is lower – at least for local investors. As a result, many of the international studies about the impact of cutting corporate tax rates are not readily applicable to Australia.

Local shareholders do get one small benefit from cutting corporate tax rates. If companies pay less tax, then they have more to reinvest, so long as the profits are not paid out to shareholders. Yet in practice, most profits are paid out. Therefore a company tax cut will generate little change in domestic investment.

By contrast, foreign investors do not benefit from franking credits. They pay tax on corporate profits twice: first at the company tax rate, and then as income tax on the dividends. This means that a cut to the company tax rate provides big benefits to them.

This week The Australia Institute pointed out that foreign investors from the United States and other countries that have tax treaties with Australia may not benefit from the company tax cut, because their home governments will collect the gains from any cut to Australia company tax as additional company tax. Yet this would only occur when foreign firms repatriate profits earned in Australia to the home country.

The big reductions in net tax revenue – and therefore the large benefits to companies – are expected when the corporate tax rate is cut from 30% to 25% between 2022 and 2027 for larger companies, including the bulk of businesses that are foreign-owned.

The headline from the Treasury modelling for the 2016-17 Budget is that this cut will ultimately increase GDP by up to 1.2% meaning larger foreign companies are attracted to invest more in Australia. The finding is based on work contained in a Treasury research paper that modelled the long-term impact of a company tax cut.

Activity is not income

However, it is a mistake to assume that all the increase in economic activity will make Australians better off. We often use Gross Domestic Product – the sum of all economic activity – as a short-hand measure for prosperity. But when the benefits disproportionately flow to non-residents, GDP can be misleading. It’s much better to look at Gross National Income (GNI), which measures the increase in the resources available to resident Australians.

Treasury expects that cutting corporate tax rates to 25% will only increase the incomes of Australians – GNI – by 0.8%. In other words, about a third of the increase in GDP flows out of the country to foreigners as they pay less tax in Australia. And because most of the additional economic activity is financed by foreigners, the profits on much of the additional activity will also tend to flow out of Australia.

You don’t get something for nothing

Yet even this increase in GNI of 0.8% is not the best estimate of the improvement in living standards Australians can expect from the Government’s company tax plan. If company taxes are lower, other taxes have to be higher, all other things being equal. In the modelling discussed so far, Treasury first assumes that these revenues can be collected by a fantasy tax that imposes no costs on the economy.

But that’s not what happens in the real world. So the Treasury research paper also models the scenario in which personal income taxes rise to offset the reduced company tax revenue. On this more realistic assumption, Treasury estimates that GNI will increase by just 0.6% in the long term, or roughly $10 billion a year in today’s dollars.

Other wrinkles in the story

Even this more modest Treasury figure may well over-estimate the long-term boost to GNI. In the real world, progressive income taxes impose higher costs than the hike to a hypothetical flat-rate personal income tax that Treasury modelled. Companies may also not increase investment as much as Treasury expects, and those firms that are part of oligopolies in Australia may not increase wages by as much as Treasury assumes.

While these are reasons to expect that the Treasury modelling overestimates the economic benefits of a company tax cut, they are offset by some more conservative assumptions. Treasury believes that tax cuts modestly change how much firms shift profits overseas; it may overstate how much tax cuts flow into additional profits rather than higher wages in those industries that it does recognise as oligopolies; and it may discount the benefits of investors making less distorted choices between debt and equity funding.

The verdict on the first claim

The bottom line is that, on Treasury’s own modelling, a corporate tax cut will increase Australian incomes in the long term by up to 0.6%. The Treasury research paper doesn’t commit itself to a timeframe, but it cites other work that expects the economic benefits of company tax cuts to take 20 years to bear fruit, with half the benefit in 10 years. Given that the important (and expensive) part of the corporate tax cuts only starts to take effect from 2022, Australia will be waiting 25 years for a 0.6% increase in incomes.

This economic benefit needs to be seen in context. If Australian per capita GDP and GNI increase at 1.5% a year (as the budget papers routinely assume), then over 25 years, incomes will rise by 45.1%. Corporate tax cuts mean that instead, incomes will rise by 45.7% – or perhaps a bit less. It may still be worth doing, but it’s not a plot twist that dramatically changes Australia’s story.

Others claim that in the past, company tax cuts have had no measurable effect on the economy. This is disputed – there may well be a link between corporate tax cuts and economic growth. But it’s inevitably hard to see in practice because on Treasury’s own modelling the economic effect of company tax cuts is small relative to other changes.

Not four-to-one, more like dollar for dollar

This brings us to the Government’s second claim. Late last week, Mr. Turnbull said that each dollar in company tax revenue cut would deliver an extra four dollars in GDP.

His claim appears to be drawn from an earlier 2015 Treasury research paper that modelled the economic impact of major Australian taxes, including company tax. The more recent Treasury working paper, released in Budget week, implies a slightly larger $4.30 increase to GDP from each $1 in revenue cut.

But again this misses a big part of the story.

First, this claim is about GDP, and therefore includes the disproportionate increase in the income of foreigners. Our analysis of the Treasury modelling shows that the increase to Australian incomes, or GNI, is only $2.80 per dollar of revenue lost from a corporate tax cut.

Second, when corporate tax is replaced by a still hypothetical but marginally more realistic flat rate income tax – rather than a complete fantasy tax that has no impact on the economy – the increase to Australian incomes is less again: only $1.80 per dollar of revenue lost.

Third, the Prime Minister has framed the boost to the economy in terms of the long-term increase to GDP per dollar of company tax cut. Treasury calculates the revenue “dollar” lost after considering the additional tax revenue that the government hopes to collect from all taxes in twenty years time as incomes rise because of greater investment.

Many people would interpret the Prime Minister’s statement to compare the ultimate benefit per dollar of tax revenue given up in the shorter term. On this basis, the increase to Australian incomes in the long term is only $1.20 for every dollar given up in the short term as a result of corporate tax cuts.

This story ends the same way. Corporate tax cuts may be worth doing, but the outcome is unlikely to set pulses racing.

The journey matters

So far, as the Treasury research paper does, we’ve focused on the long-term economic boost from a company tax cut once the economy has fully adjusted. But the journey to get there also matters.

For a decade, a cut to corporate taxes will reduce national income. Foreigners will pay less tax on the profits from their existing investments in Australia, reducing Australian incomes. Foreigners own about 20% of all capital in the economy, so it’s a big windfall gain for them. We estimate that when a 5 percentage point tax cut for big business is first implemented, national incomes will be reduced by about 0.5%, as a result of the immediate loss in company tax revenues formerly paid by foreign investors.

The benefits to Australians from a corporate tax cut only accumulate slowly as foreigners make additional investments. Treasury cites a paper that estimates that the benefits of corporate tax cuts take 20 years to flow through. Assuming that these benefits increase at a constant rate, Australian income will only be larger than otherwise after about 10 years.

Of course, the upfront costs of a company tax cut over the first decade must be offset against the long-term gains. On our estimates, the loss of income incurred over the first decade will only be offset by higher incomes after about 19 years. If Australians want the modest economic benefits of a corporate tax cut, they will be waiting a long time.

The moral of the story

Company tax cuts are not a knight in shining armour to save the Australian economy. On the basis of the modelling that the government uses to support its case, corporate tax cuts can make a modest contribution, and then over the very long term. That story won’t sell as many copies. Truth, on this occasion, is duller than fiction.