Newly-minted Nobel Laureate Professor Brian Schmidt reflects on the state of Australian science. The feted astronomer is optimistic about the future and the contribution science can make to improving lives in this country and across the world.

Despite my American accent, I have lived in Canberra longer than anywhere else in my life. And a lot has changed in the past 17 years.

When I arrived in Australia in 1994, it was a well-off country separated by vast oceans from the rest of the world. Today, Australia is one of the world’s wealthiest countries, gateway to the fastest growing part of the world economically, Asia.

We have come of age. The world is rapidly changing, and Australia is in a unique position to shape its future for the century ahead.

11 years ago I received the first Malcolm McIntosh Prize for Physical Scientist of the Year. I was struck with complete wonderment.

When I came to this country, Australia didn’t have science awards dedicated to its own researchers. Now, we celebrate our nation’s best scientists and educators on our own terms.

The Malcolm McIntosh Prize was, in fact, the first award I received for my work on the accelerating Universe, setting off a progression which culminated in last week’s Nobel Prize announcement.

It is a sign of our nation’s confidence that my home country was able to recognise my part in this discovery first.

Investing in education

I often hear it said that science and education policy never won an election. But nations rise and fall on the outcomes of science and education.

Improvements in our lives are largely due to technology powered by these endeavours. The lack of political acknowledgement of this may be because science and education do not run on a three-year cycle. It takes decades for such policies to run their course, but they provide a similarly long legacy.

The policy makers of this generation have a unique opportunity to shape the long-term prosperity of this country. Using the opportunities that arise from a prosperous, agile economy, Australia can ensure its future in a rapidly changing world through a strategic vision of, and investment in, education, science and technology.

The education part of this triumvirate is straightforward. Australia needs a workforce educated commensurate with its wealth. To put it simply, we need the world’s best educated workforce. This is the engine of future prosperity.

It should not be surprising that my high school education was sensational. I grew up in Alaska during the oil boom. Alaska paid teachers based on their ability, and paid them exceedingly well, relatively speaking. Among my teachers was a man with a PhD in chemistry from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

We should be smart and learn from tonight’s award recipients, but ultimately, as in Alaska, it will cost money, and it will take time.

This, however, has to be at the top of our agenda. And, in relative terms, it really isn’t that expensive — 12 years of good education provides a 50-year legacy. I applaud the beginning of the education revolution, but we must let the revolution continue.

How science makes money

Science is the building block of future technological breakthroughs. Basic science research creates revolutionary new ideas. It’s a messy process, but it is the process that has taken our world from the Dark Ages to where we are today.

2009 Prime Minister’s Prize for Science recipient John O’Sullivan started out by trying to discover evaporating black holes.

He never found any, but he did end up helping invent the Wi-Fi system we all now use. And the royalties flowing back to Australia from his work are just the beginning. His achievement has increased productivity not in just Australia, but around the world.

This year, we honoured Professors Ezio Rizzardo and David Solomon who have used their basic research in polymers to open a whole new way of making innovative products. Again, significant royalties will flow from their inventions back to CSIRO.

Professor Solomon was also largely responsible for Australia’s plastic banknotes. So science really does make money — directly!

Taking Australia to the world

Scientific research thrives in world-class institutions. Australia should strive to strengthen its universities, and also ensure CSIRO remains the unique research institution it is.

We must work towards having at least one university in the top ten internationally, and three in the top 50.

Then there is the process of taking science and technology to market. This has traditionally been hard. Australian companies have found it difficult to capitalise in our small domestic market — in both senses of the word.

But this is an area in which the world order is changing. If Australia works with partners on a more international basis, it will be better able to transform its good ideas into goods and services in the global marketplace.

Working internationally is challenging for governments — a posture here, a step there. Progress is painfully slow. But for scientists, it comes naturally. We routinely work together in the pursuit of knowledge. So science can be a conduit to take Australian industry to the world.

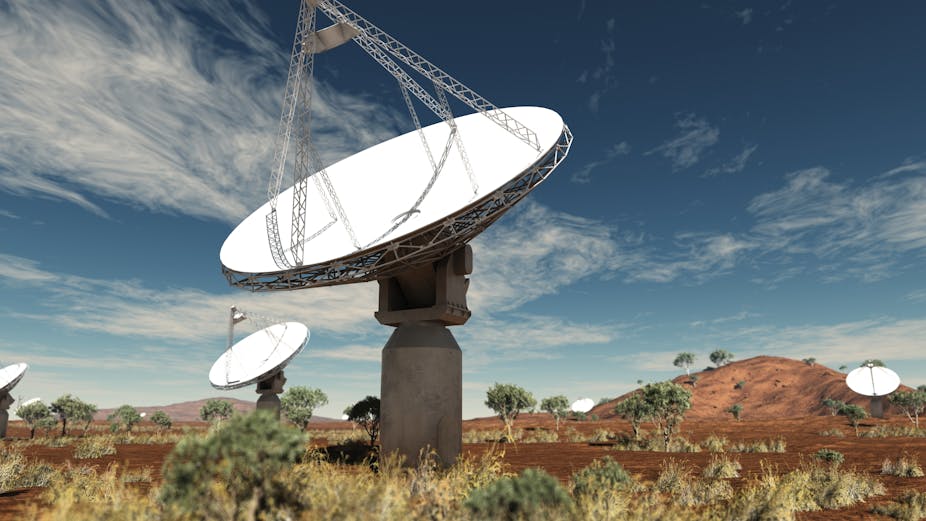

Over the past five years, with the support of CSIRO and the Commonwealth Government, Australia has pulled out all the stops in putting in a superb bid to host the Square Kilometre Array Telescope in Western Australia.

This next-generation radio telescope will enable astronomers around the world to make fundamental discoveries about our universe. But it will also facilitate opportunities for Australian companies to work with their European, Asian and North American counterparts, creating linkages everywhere.

But the Square Kilometre Array is only one of many such international projects. Not all, of course, will be based in Australia, and not all have equal merit. But involvement in a portfolio of such projects can provide a wealth of scientific and industrial opportunities within the international landscape.

A new generation of science stars

The future for Australia is indeed bright — but it is not guaranteed. Capitalising on Australia’s opportunities will not just happen by itself, it requires strategic science and education policies that adapt to a changing world. And Australians will have to be willing to make significant changes in how they go about their business.

But we have the ingredients for success:

great teachers, such as Prime Minister’s science teaching prize winners Brooke Topelberg and Jane Wright, to whom we can look for guidance on future education policy; and

great scientists, such as winners Min Chen, Stuart Wyithe, Ezio Rizzardo and David Solomon, who enrich our world with new ideas.

While I cannot predict whether this year’s Prime Minister’s Science Award recipients are future Nobel Prize winners in the making, it matters not. Their work requires no further validation.

This is an edited version of a speech given at the presentation of the 2011 Prime Minister’s Awards for Science at Parliament House in Canberra on Wednesday October 12.