Over the past few weeks, Australia’s grand mufti, Ibrahim Abu Mohamed, has been criticised by government MPs and sections of the media over his response to the Paris terror attacks.

Resources Minister Josh Frydenberg argued that the grand mufti’s comments were a “graphic failure”. He continued:

He [the grand mufti] has more of a responsibility not only to the Muslim community but to the community at large.

Immigration Minister Peter Dutton added that Islamic leaders should unequivocally condemn the attacks:

There are young people who hang off every word that’s said … these young people who are being radicalised online need counter messages.

Despite the belief that the grand mufti can – and should – crystallise the sentiments of Australian Muslims, given their sheer diversity, how representative is he of the broader community?

If we focus on the structure and “representatives” of communities, there have been episodes in Australian history from which we can draw a few elements of comparative experience. Of these, the story of German migration to South Australia can highlight the experience of diverse communities, and what can occur to them in a time of serious conflict.

Church, farm and vines

Germans in pre-first world war South Australia have primarily been viewed as “Barossa Lutherans” – a pious, hard-working group of rural migrants who, seeking refuge from religious persecution, contributed to South Australia’s development.

There is truth to the stereotype. Of about 10,000 Germans who migrated to South Australia between 1838 and 1914, the vast majority settled in the Barossa Valley and rural districts of the Adelaide Hills. Many continued to participate in the “life-cycle” rituals offered by church sacraments, such as baptisms and marriages. German-language schools also maintained their importance for the rural communities.

However, when the first waves of migrants arrived in South Australia in the 1830s and 1840s, Germany did not exist. These “Germans” were Austrians, Brandenbergers, Pomeranians and Silesians – separated by confession, regional dialects, laws and traditions.

Likewise, while Muslims in Australia may be bound together by a common religion (also taking into account denominations like Sunni and Shi'a), the community constitutes a large number of nationalities. It spans numerous languages and cultures, with about 38% of the community born in Australia.

From the late 1840s, the socioeconomic and occupational profile of German migrants became increasingly urban. Migrants’ lives also grew distant from the auspices of the Lutheran Church under pastors August Kavel and Gotthard Fritzsche.

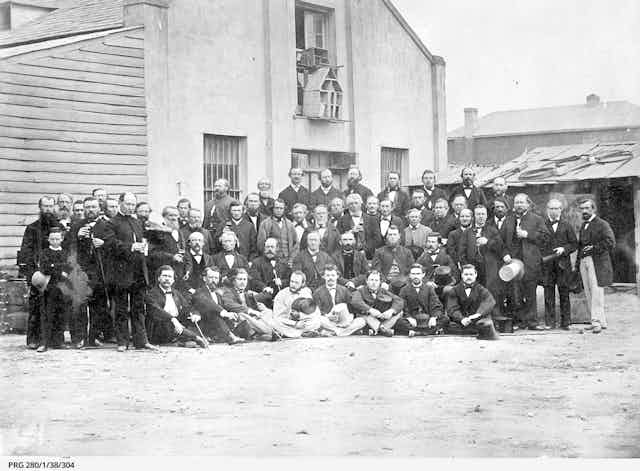

In 1854, a group of middle-class Germans established the Deutsche Club (German Club). From their grand rooms on Pirie St, the club’s members represented a mixed identity – embracing their home in South Australia and the emergent discourse surrounding German nationalism.

Members of the club – including men (women were generally left to the domestic sphere) like Friedrich Basedow, Friedrich Krichauff and members of the Homburg and Muecke families – would become community leaders.

In embracing roles as members of state parliament, German-language newspaper proprietors and justices of the peace, such Germans sought to bridge the city-country divide among migrants – uniting South Australia’s portion of the German diaspora.

German migrant experiences

Between the late 1870s and the mid-1880s – on the back of attempts to induce the arrival of “sound” German migrants via cheap passage fares and promises of land – a number of working-class migrants made their way to Adelaide.

In 1886, a group of them founded the Sued-Australischer Allgemeiner Deutscher Verein (South Australian General German Association), which attracted upwards of 600 English- and German-speaking members by the turn of the century. Drinking, dancing, rifle shooting, singing, stage performances and picnics were a few activities available to members.

The Verein became an important node within the network of “democratic societies” operating in Adelaide. This in no small part led to the formation of the United Labor Party in 1891.

The relationship between middle- and working-class Germans was, at best, frosty. Noting the sale of the Deutsche Club building in 1897, a member of the Verein wrote to The Advertiser:

I am sure scores of my countrymen will consider the place better employed as a warehouse … than that half-a-dozen Tories should use it for talking platitudes about the German Empire.

Whereas members of the Deutsche Club sought to promote “deutschtum” (German language, culture and customs), members of the Verein sought to advance the aims of social democracy and the broader labour movement. These examples go some way in problematising notions of an essentialist “German” community.

Similarly, the Australian National Imams Council is but one of a large number of Islamic organisations in Australia. Some reflect national divides but also attempt to reach across them through grassroots community organisation, such as the Lebanese Muslim Association. Others focus on gender issues.

Conflict and implications for identity

Following the outbreak of war in 1914, anti-German sentiment overrode acknowledgement of such diversity.

Germanophobia and the curtailment of civil liberties were expressed in the internment of “Germans” on Torrens Island, closure of social clubs and schools, calls for resignation from public office and the renaming of “German” towns.

Given this example, as well as the current debate surrounding Muslim “radicalisation”, we could perhaps look to comprehend migrant and minority communities from the grassroots up. We could look more critically at all-encompassing notions of a particular “group” and those who claim to speak for it.

In doing so, we may have a better chance of assessing and resolving the problems facing immigrants and minorities in Australian society.