Prisons are places of suffering. But in theory, they aim for something beyond punishment: reform.

In the United States, the goal of prisoner rehabilitation can be traced back, in part, to the 1876 opening of the Elmira Reformatory in upstate New York. Purported to be an institution of “benevolent reform,” the reformatory aimed to transform prisoners, not just deprive them – though founder Zebulon Brockway, known as the “Father of American Corrections,” was notoriously harsh.

Other states soon adopted the reformatory model, and the notion that prisons are places to “correct” people has become a staple of the judicial system.

But the idea that imprisonment and suffering were supposedly good for the prisoner didn’t emerge in the 19th century. The earliest evidence goes back some 4,000 years: to a hymn in Mesopotamia, in modern-day Iraq, praising a prison goddess named Nungal.

Almost a decade ago, as a graduate student researching slavery in early Mesopotamia, I came across numerous texts dealing with imprisonment. Some were administrative documents dealing with everyday accounting information. Others were legal texts, literature or personal letters. I became fascinated with imprisonment in these cultures: Most of them detained suspects only briefly, but in literary and ritual texts, imprisonment was seen as a transformative, purifying experience.

The ‘house of life’

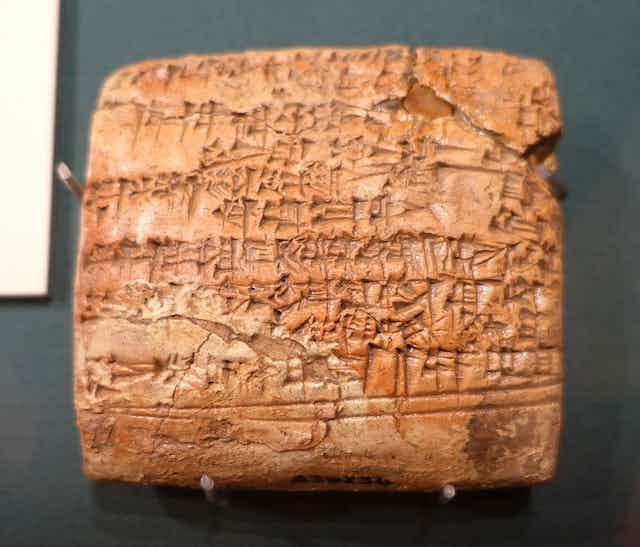

Around 1,800 B.C., students training as scribes at Nippur, an ancient Sumerian city, frequently copied from a selection of 10 literary works. Using cuneiform, these aspiring scribes would copy texts that included the exploits of the legendary hero Gilgamesh as he fought the beast Huwawa, the fearsome guardian of the forest. They wrote about a great Mesopotamian king named Šulgi, who claimed to be a god.

And as the master scribe dictated these various texts, the students also heard about a prison goddess named Nungal.

Though her justice was inescapable, Nungal was also celebrated for her compassion. Her “house” brought suffering upon prisoners, whose sorrow gave rise to lament. Through that lament, however, prisoners could be purified of their sins and made right with their personal gods, who were their protectors and mediators before the greater gods.

The “Hymn to Nungal,” which dates from the second or third millennium B.C., details how a guilty prisoner sentenced to death was not killed, but snatched “from the jaws of destruction” and put in Nungal’s house, which she calls a “house of life” – but also a place of suffering, isolation and pain.

Still, the hymn describes prisoners transformed by their time in prison. The goddess says her house is “built with compassion, it soothes the heart of that person, and refreshes his spirits.” Eventually, she continues, they will lament and be purified in the eyes of their deity: “When it has appeased the heart of his god for him; when it has polished him clean like silver of good quality, when it has made him shine forth through the dust; when it has cleansed him of dirt, like silver of best quality … he will be entrusted again into the propitious hands of his god.”

Fact vs. fiction

The extent to which the ancients believed such stories about the gods remains a matter of debate. Were texts like the “Hymn to Nungal” matters of sincere religion or just fairy tales that no one took seriously?

Since it is a literary text, it is not a reliable source about the justice system, either. Mesopotamian kingdoms during that time seem to have used prisons to detain suspects prior to punishment, similar to jails that hold suspects before trial today. They also detained people to force them to pay a fine or debt, and to coerce labor – sometimes for over three years. But punishment, which typically involved physical or financial consequences, did not include time in prison.

Still, detainment entailed suffering, with one prisoner describing the “prison” as a “house of distresses or famine” in a letter written to his superior. In another text, the sender says he was released but complains of beatings that another prisoner endured as part of the investigative process – although the sender does not mention the nature of the suspected offense.

However, scholars Klaas Veenhof and Dominique Charpin have found evidence of Nungal playing a role in the judicial process. At some temples, oaths would be taken in the presence of a throw-net, similar to what is used to cast for fish, which symbolized Nungal and inescapable justice.

The vision cast in the hymn was likely folded into a later ritual practice where imprisonment was used to purify the king. During the New Year festival, the king was stripped of his regalia and entered a makeshift prison made of reeds, where the king offered prayers to the gods for his sins. Through prayer and ritual, he was deemed purified and able to resume his royal duties.

Yesterday and today

While most people may not have spent long periods in Mesopotamian prisons, they did suffer in them. Perhaps it is that experience that caused a text like the “Hymn to Nungal” to be written, exploring how such an experience could be used to reform the prisoner through lament.

The notion that imprisonment can be good is pervasive, but is it accurate? How prison systems think about reform is very different today than how the “Hymn to Nungal” envisions it. Yet the powerful idea that suffering can be good for prisoners has deep historical roots – allowing incarceration systems to claim that the suffering within their walls is compassionate.