Witches have long been an international obsession. From King James I’s book [Demonologie](http://arcticbeacon.com/books/King_James_VI-DAEMONOLOGIE(1597) (1597) and the famous Pendle witch trials in Lancaster (1612), to Shakespeare’s Macbeth (first performed 1611) and Matthew Hopkins’ The Discovery of Witches (1647), there are countless factual and fictional tales of witchcraft. The recent release of the film, The Last Witch Hunter, is yet another example of this cultural fascination.

But the colourful, fictional yarns often are far removed from the reality of witchfinders and the trials that the accused – mostly women – faced. And, in some cases, are much more a reflection of contemporary anxieties.

The 17th century witch trials staged in Newcastle upon Tyne, for example, offer a stark glimpse of the reality, complicating our received understanding of history as represented in film and fiction. The simple paradigm of the self-interested mercenary (witchfinder) in pursuit of the disenfranchised victim (witch) is rendered more complex by the social, political, gender, and economic contexts of the age.

In 1650, towards the end of the English Civil War and within memory of a 1636 outbreak of plague, Newcastle upon Tyne’s Puritan magistrates invited in an unnamed Scottish witchfinder. Known as the “bell-man”, he asked “all people that would bring in any complaint against any woman for a witch, they should be sent for and tried by the person appointed”.

There was also an implicit financial motive in his endeavours – for each successful prosecution, the Scottish witchfinder would receive 30 shillings, about ten times the average daily wage.

A bloody affair

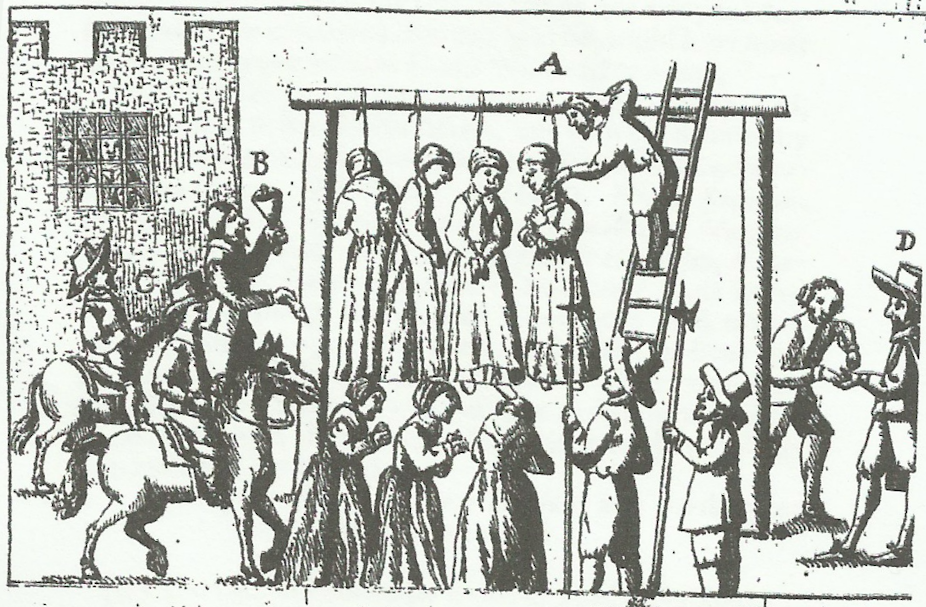

In 1655, Ralph Gardiner’s England’s grievance discovered, in relation to the coal-trade recorded an account of the Newcastle witch trials that followed. He noted that 30 women were brought to the town hall, stripped, and “pricked” by a bodkin or pin, the evidence gleaned resulting in the public execution of 16 people (including one man). One woman, Margaret Brown, implored God to give some sign of her innocence – and, at her execution, Gardiner recorded, “as soon as ever she was turned off the ladder her blood gushed out upon the people to the admiration of the beholders”.

While many of the accused in such cases were old, economically disadvantaged and female, this was not always the case. Gardiner also demonstrates this in his account, offering a somewhat romantic challenge to the stereotype of the old crone.

The Scottish witchfinder, for example, claimed that he could identify one witch by her appearance. In response, Lieutenant Colonel Hobson (who served in the parliamentarian New Model Army and was deputy governor of Newcastle) protested that by this logic, such a young and attractive woman could not be a witch. Her public trial, in a pseudo-sexual gesture, involved the exposure of her body up to her waist, after which she was eventually cleared of being “a child of the devil”.

Various other accounts of witchcraft in north-east England identify occurrences such as visions of headless bears, and one woman being ridden like a horse to a Witches’ Sabbat.

Modern anxieties

Given such stories, it is no surprise that witches and their craft have pervaded contemporary culture. Famous literary examples include Arthur Miller’s The Crucible (1953), and Jeanette Winterson’s more recent novel, The Daylight Gate (2012). Then we have American Horror Story: Coven (2013), a TV show addressing the legacy of the Salem witches (1692).

Film representations also offer us some problematic insights into recuperating the idea of the “witch-hunt”. The Witchfinder General, directed by Michael Reeves (1968), for example, says much more about the time in which it was filmed than the historical truth.

In the film, Matthew Hopkins (Vincent Price) and his sidekick John Stearne (Robert Russell) seem to have sole responsibility for condemning witches. Historically, however, this was a joint effort between the witch hunters, local people and town councils – witchfinders often worked with the support of the local authorities.

Instead, The Witchfinder General articulates American anxieties regarding traditional authority around the time of the Vietnam War (1955-1975). The film’s portrayal of corruption, and the implied lack of confidence in the political administration are suggestive of that contemporary moment. There was also revulsion at the time to the strong sexual and violent imagery in the film. The playwright Alan Bennett said it was: “The most persistently sadistic and morally rotten film I have seen.”

The recent release of The Last Witch Hunter also reflects contemporary concerns. Vin Diesel’s character, Kaulder, asks at one point if we are to judge a witch “without interrogation”. In this scene, the witch is brought to trial with a hood over his head, recalling the alleged abuses at Guantanamo Bay.

Rose Leslie’s character in the film, a goth woman named Chloe, also challenges some of our more stereotypical views of witches, as did the attractive teenage witches in 1996 film The Craft. She asks: “What do people know about witches anyway? That we’ve green skin and pointy hats and we’re mean?”

Despite this corrective, she also circulates some common mistakes, referring to the witches who were “burnt at the stake in Salem”. Of course, history tells us that the Salem witches were put to death by hanging.

So how can we understand the pervasive image of the witch? The problem with presenting witch-hunts for modern-day audiences is that it presupposes one coherent set of historical beliefs and procedures. In fact, the real witch trials were far more complex than some popular cultural material might suggest.