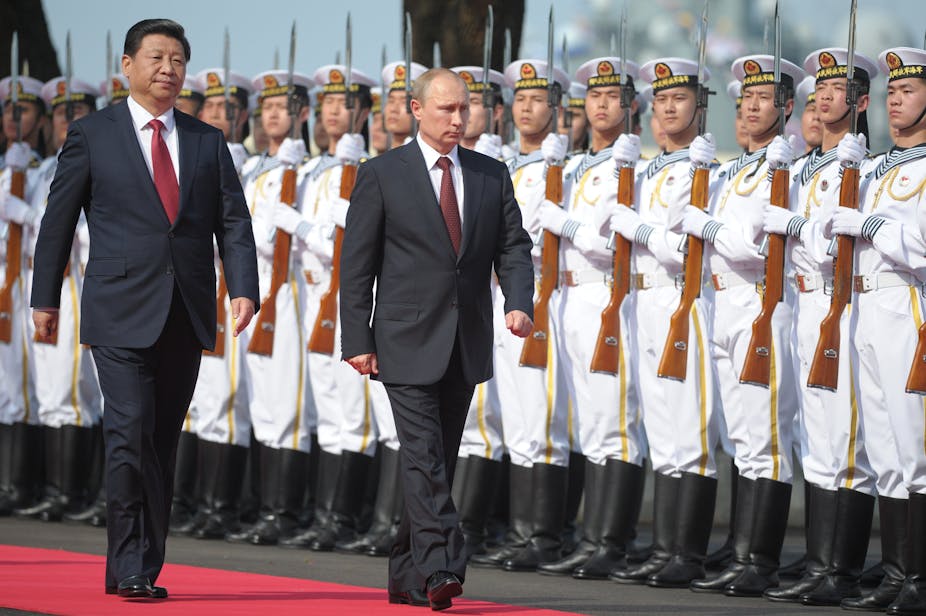

The headline accomplishment of Vladimir Putin’s trip to China is hard to deny: a 30-year deal estimated to be worth US$400 billion for Russia to deliver gas to China. But it isn’t the unqualified win that Putin’s supporters might claim. For Russia has been backed into a corner.

This visit is the latest in a series of moves by the Russian president to strengthen economic relations with Asia. Last year, Putin, apparently taking a leaf out of US President Barak Obama’s book, announced a new “pivot to Asia” strategy, in the hope that Russia will be able to leverage the perceived economic dynamism of countries like China and South Korea to its advantage. Russian elites increasingly feel that Asia, and especially China, is a more dynamic economic region than the West and one that comes with less political baggage.

The pivot East is also viewed as a reason to boost the development of Russia’s far east. This region might be full of valuable natural resources but it suffers from a sparse and declining population and a neglected economy. Success for Russia in China would provide much-needed respite from Western criticism. It might also signal that Russia sees its economic future in Asia and not in Europe.

But this raises important questions about Russia’s future role in the global economy. How important is Asia to the Russian economy? How would Russia’s economic relations with Asia need to change to cement its place in the Asian economy? And would moving the economic centre of gravity to the East help modernise Russia and increase its influence in the global economy?

Rapid growth

Russia’s trade with Asia has grown rapidly over the past decade. In 2000, the northeast Asian trio of China, South Korea and Japan accounted for just 5.5% of total Russian imports. By 2012, this figure had grown to 25%. Russian exports to the region also grew, albeit at a slower rate. In 2000, the three Asian countries accounted for 7.5% of total Russian exports; by 2012, 12.5%.

Thus, Russia’s turn to the East is not new, and is certainly not a direct result of unrest in Ukraine. Instead, as the global centre of economic gravity has shifted from the Atlantic to the Pacific, so have Russia’s trading relations.

But this doesn’t mean a turn away from Europe. While trade with Asian countries has grown at a brisk rate, European countries, especially Germany, the Netherlands, and Italy, continue to account for the majority of Russia’s foreign dealings. European economies also provide vital technology and know-how to Russian industry.

A look at Asian investment in Russia also reveals serious gaps in economic integration. Even after a number of high profile energy and infrastructure deals, China, South Korea and Japan account for just over 1% of foreign investment in Russia. So while Russia may be importing a growing volume of goods from Asia, it still turns overwhelmingly to Europe for capital.

Such dense trade links between Russia and Europe took decades to form, dating in many cases back to the height of the Cold War. If the two managed to trade amicably during the Cuban Missile Crisis, they shouldn’t have a problem now. So Europe will most likely remain Russia’s key economic partner for years to come as it continues to provide capital, technology and demand for Russian energy. While the economic pivot to Asia is real, this is Russia looking for some more friends, not an entirely new set of friends.

Energy exports

Russia is the world’s largest exporter of natural gas, the largest exporter of refined oil products, and the second largest exporter of crude oil. China, South Korea and Japan are all energy deficient countries that rely on imported fuels to power their economies. This symmetry of supply and demand suggests that Russia should perform the role of key energy supplier to the Asian economy.

So far though, Russian energy exports have been relatively modest. The three Asian countries accounted for around 13% of total Russian fuel exports in 2012. This shallow relationship is perhaps more vivid when viewed from the Chinese side. China is the world’s largest importer of oil and yet just 6% of it comes from Russia. Angola and Oman both provide more. Russia supplies just 4% of Japan’s imported oil.

So why does Russia exports so little energy to Asia? Energy trade requires expensive investment in oil rigs and wells, transportation infrastructure such as pipelines and gas terminals, as well the legal and commercial networks to distribute energy in the destination countries. Energy exports to Asia have been limited by the speed with which supporting infrastructure can be put in place. This takes a long time, as it did when the Soviet Union built up its vast energy trade with Europe during the Cold War, and requires a convergence of favourable political and commercial conditions.

Putin no doubt hopes that the deals concluded with Asian leaders over the past few years will pave the way for a massive expansion of energy exports to the region. There has certainly been enough political capital expended on securing a favourable outcome. However, Russia will need to provide the necessary conditions on which a relationship based on trust can be built. To achieve this, Asian partners will want to agree on mutually acceptable prices and terms of access to oil and gas fields, and transportation infrastructure. It is precisely in this area that talks have often failed in the past.

Despite the success of Putin’s visit, the majority of Russia’s energy exports will continue to go to the West. Even if the gas supply deal is fully implemented – something that is far from certain – China will import at most around 38 billion cubic metres (bcm) of Russian gas annually. To put that into perspective, Russia exported 161.5 bcm of gas to Europe in 2013, with Germany alone receiving 40.1 bcm. And increased Chinese involvement in new projects will not change the fact that Western technology and know-how will still be crucial to exploiting oil and gas in hard to reach areas of the Arctic and Siberia.

What exporting energy to Asia will do is provide a level of protection from any deterioration of economic and political relations with European customers in the future. It may also revitalise Gazprom, which is facing European Commission antitrust charges and has been suffering as a result of increased competition from domestic rivals Rosneft and Novatek.

Smart move?

Thus, the economic basis for any putative pivot to the East is mixed. Trade flows with Asia have grown quickly, but investment links remain weak. Energy trade is likely to increase, but wider economic ties, such as Russian non-energy exports, are less apparent. It may be a while before the pivot rhetoric is matched by the reality.

Assuming Russia does succeed in shifting its economic centre of gravity to the East, will this necessarily prove to be beneficial to its economy? On the positive side, any increase in economic relations between Russia and Asia will surely boost Russia’s bargaining position when negotiating future trade deals, especially in the realm of energy.

But there are a number of potential problems. The first is that Russia needs to invest in costly infrastructure in its Far East (roads, railways, pipelines, and so on) if it is to fully engage with Asia’s growing economy. Any such spending will require massive private and public investment, and it is far from clear whether such spending will materialise.

The growing asymmetry between Russia and China may be even more important. Quite simply, the Russian economy is dwarfed by that of China, and the gap between the two is growing. For Russia, and Putin, the prospect of closer ties with its largest neighbour offers a tantalising prospect: an economic and political counterbalance to the West at a time when relations with the US and Western Europe are at a 20 year low.

However, the Chinese are not under any such pressure. Russia is a relatively minor trade partner, accounting for just over 2% of China’s total trade. With Russia’s relations with the West deteriorating it is more likely that in the recent negotiations China was able to exploit Russia’s relative isolation and secure more favourable terms. Russia also needed to sign a deal relatively quickly as the prospect of new exports from the likes of Australia, Qatar, central Asia, and east Africa threaten to cause a gas glut. Russia wanted to wrap things up before other competitors joined the market and drove prices down.

Full terms of the most recent deal haven’t yet been released, but Putin says China will pay around US$350 per 1,000 cubic metres of gas, a price similar to those charged to Europe (derived simply by dividing the headline figure of US$400 billion by the volume of gas to be delivered over the 30 year period). But this misses a vital point: Gazprom will have to pay for much of the infrastructure in Russia’s Far East, while in Europe this is already in place. Those overheads mean the deal suddenly doesn’t look so great for Russia.

China is thought to have been driving a hard bargain, and quite right too. There is no reason for it to take anything other than a purely commercial and pragmatic approach to economic relations with its northern neighbour. Russia just isn’t important enough.