I was about to set off to the airport on the morning of 10 April 1993 to cover the great American boxer Muhammad Ali’s arrival in Johannesburg when the news came through: Chris Hani had been murdered.

Of all the African National Congress (ANC) leaders I’d met during a decade of underground membership during the 1980s, the one who impressed me the most was Hani.

From 1987 to 1992 Hani was chief of staff of the movement’s military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe, and leader of the South African Communist Party from 1991 to 1993. Intelligent, brave, warm and witty, he exuded the kind of energetic charm that made him a hugely compelling revolutionary. I spent time with him in 1987 and 1989 and felt then, and later, that he would have made a far better successor to Mandela than the anointed dauphin, Thabo Mbeki.

The news of his assassination outside his home in Dawn Park, Boksburg, came as a shock. I found it difficult to focus on the appearance of Ali, who’d been a kind of hero of mine for more than 20 years.

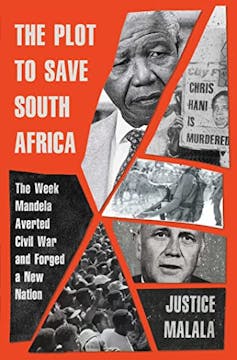

In his recently released book, The Plot to Save South Africa, journalist and author Justice Malala does a masterful job of telling the tale of Hani’s murder and the precarious spell that followed before his funeral. He describes the nine days that followed, days that contained the potential to scupper fragile negotiations to end apartheid and prompt prolonged chaos or worse.

The subtitle of this book – “The week Mandela averted civil war and forged a new nation” – is appropriately chosen.

The book is a gripping read for anyone interested in late 20th century history, and in the end of apartheid more specifically. Malala has done a fine job in making this not just an impressively researched record, but also a compelling, fast-moving tale.

Narrative balance

Malala, who was a young reporter at The Star at the time of the killing, is a talented story-teller, adept at weaving the required facts into a page-turning narrative. Each anecdotal vignette comes with the kind of vivid descriptive detail that is only possible with exhaustive research. He interviewed scores of the key players from all sides in this drama. He also had access to a wealth of archival material, allowing him to delve into the minds of the protagonists and to recount their movements, what they were wearing and the words they shared with each other.

He draws on his experience, discipline and flair as a writer to maintain the momentum all the way through to the funeral at the end.

The key player in this enthralling story is Nelson Mandela who had been released after 27 years in prison in February 1990. He adored Hani, treating the 50-year-old as his son. He was overwhelmed with sadness. But he retained the clarity of purpose to hold back ANC supporters from wrecking the negotiations to end apartheid that had started soon after Mandela’s release, and had resumed shortly before Hani’s murder, after a spell of suspension.

The assassins wanted the talks derailed. They hoped Hani’s death would ignite a civil war that would unleash the apartheid security forces against the ANC and the Mass Democratic Movement, an alliance of anti-apartheid groups, as never before.

There was indeed an outpouring of rage, grief and violence following the murder. In the areas around Johannesburg and Pretoria alone 80 people were killed and hundreds injured in violence directly related to Hani’s assassination, with many more casualties in the rest of the country.

Most of the injuries and fatalities were due to the actions of the apartheid security forces and right-wing vigilantes.

But the outcome of the assassination was the opposite to the killers’ intentions. The incendiary climate following the murder focused minds on both sides. Mandela, his lead negotiator Cyril Ramaphosa, and other ANC leaders successfully used the moment to press for an election date and a Transitional Executive Council to run the country until the first democratic election. This was hugely significant. It meant that the then ruling National Party, the party of apartheid, could no longer call the shots before the election.

Without the urgency injected into the negotiations process by the assassination, it is possible that it would have dragged on, and many more would have died.

The outcome was the opposite to the killers’ intentions. Immediately afterwards, power leaked away from the state president, FW de Klerk, the National Party and the security establishment, and flowed to Mandela, the ANC and the Mass Democratic Movement.

In his accounts of these killings Malala retains narrative balance, giving space to all of the players. For example, he devotes several pages to the murder by ANC activists of the liberal anti-apartheid teacher and activist Ally Weakley, who was tragically mistaken for a right-wing vigilante.

A far-right plot

The book starts with Mandela receiving news of the murder and quickly segues to the movements of the two men who would be convicted, the Polish immigrant Janusz Walus, who pulled the trigger, and his mentor, the Conservative Party MP Clive Derby-Lewis, and also those who assisted them, including Derby-Lewis’s wife, Gaye, and the journalist Arthur Kemp, who supplied Hani’s address (and subsequently emerged as a leading player in the international extreme-right).

Later, Malala raises the possibility that others within the apartheid security forces were aiding them. For example, the regular police investigating the murder were instructed by the Security Police not to probe into Walus’ links to his employer, the arms trader Peter Jackson. Jackson owned the car the killer used on the day, and Malala notes that the killer’s diary disappeared from the police docket, later reemerging with several pages missing.

He also points to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission finding that Walus operated as a source for the National Intelligence Service (the apartheid state’s version of the CIA). The commission probed human rights abuses by the apartheid state and those who fought against it.

To maintain the hour-by-hour tension, Malala avoids reaching ahead, instead portraying the players in this drama as they were then. Perhaps inevitably, some of those who star in his account fared less well in the decades that followed – in particular the ANC spokesperson Carl Niehaus, who confessed to fraud and was eventually expelled from the ANC.

More generally, many of the devoted ANC leaders who played a central part in the build-up to Hani’s funeral went on to become multi-millionaires, more interested in self-enrichment than the common weal.

Appropriately, Malala resists the temptation to speculate about what would have happened if Hani had lived. Instead he closes with Mandela and De Klerk winning the Nobel Peace Prize and the launch of the Transitional Executive Council which ushered in the largely peaceful elections on April 27 1994.

This book serves as a reminder of how close South Africa came to civil war in the countdown to democracy. Nearly three decades on, it is also a timely reminder of the selflessness and dedication of many of the main players of the time, qualities that seem in short supply today.