A string of events earlier this year provided a sobering snapshot of a global climate system out of whack. Europe suffered devastating floods, Britain’s coastline was mauled, and the polar vortex cast a US$5 billion economic chill over America. Meanwhile, an abnormally mild winter in Scandinavia disrupted bears’ hibernation; while Australia was ravaged by fires and record-breaking heat.

These happenings give us an idea of what life must have been like in the lead-up to the Holocene Epoch, living on the brink of seismic change, amid a series of abrupt climate shifts.

As the archaeologist Steven Mithen wrote in his book After the Ice:

People were thin on the ground and struggling with a deteriorating climate … massive ice sheets had expanded across much of North America, Northern Europe and Asia. The planet was inundated by drought, sea level had fallen to expose vast and often barren coastal plains. Human communities survived the harshest conditions by retreating to refugia where firewood and foodstuffs could still be found.

Since then, we have been lulled into a false sense of security by the ensuing 10,000-odd years of peaceful, stable climate during the Holocene itself. This has allowed us to tame crops and livestock, and to come together to form communities, villages and, ultimately, cities.

But the calm and tranquil Holocene has now been replaced by the Anthropocene – heralding a return to a volatile and destructive climate. Truly, we have woken an angry beast from its slumber.

From ice age to rapid warming

When the last ice age began to teeter 14,700 years ago, meltwater began to pour into the oceans, raising levels by up to half a metre per decade. The sea moved inland like a slow tsunami.

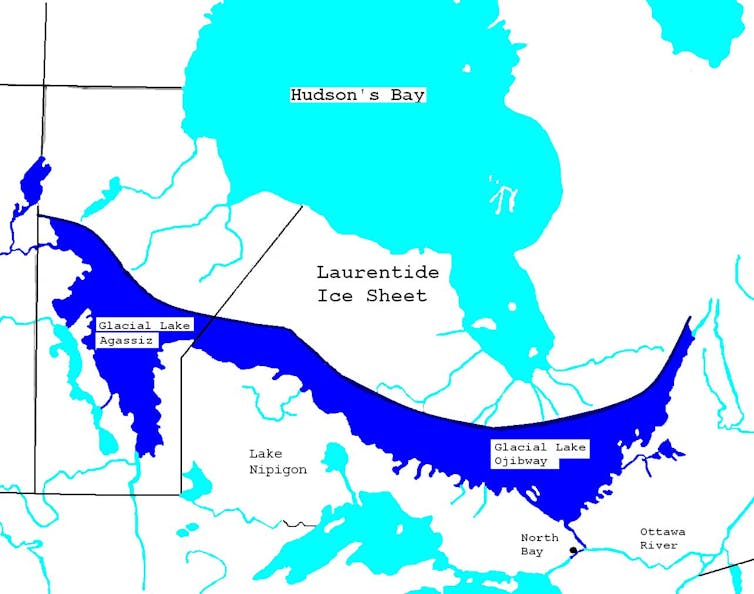

But after a hesitant couple of millennia of warmer conditions, the cold was back with a vengeance, turning western Asia and Europe into ice empires. This event, dubbed the Younger Dryas, derived from the collapse of the ice walls on Lake Agassiz in North America, sending freshwater flooding into the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. As a result it cut back the Gulf Stream, returning the planet to cool and dry conditions in a matter of decades, with the average Northern Hemisphere temperature plummeting by 7C.

These cold conditions lasted for about 1400 years. Then, just as rapidly, the warm and wet conditions returned, marking the beginning of the Holocene about 11,700 years ago.

Stable era

Since then, the world’s climate has remained remarkably stable – boring, even. The relatively static shorelines have made farming, fishing, towns and cities possible.

Humans have got used to thinking that this is a natural state of affairs. But, as James Hansen has declared, “it’s our relatively static experience of climate that is actually exceptional”.

Of course, there have been divergences from the norm, although these have thankfully been few and far between. One was 5000 years ago, when the Sahara went from a land of hippos and giraffes to desert in a mere 100-200 years.

That event was caused by gradual changes to the Earth’s orientation towards the Sun. It shows us that even when the forces are gradual, the climate may not always respond gradually but instead can move in juddering, unpredictable shifts.

At about the same time, seismic change was happening in our own midst, with the eruption of Mount Gambier sending an ash plume up to 10 km high – an event that would have partially obscured the Sun.

Eruptions like this were the main cause of climate variability in the Holocene, causing cooler, drier episodes such as the “Mediaeval little ice age”.

Things are different now

Now, however, carbon dioxide has reached levels not seen for at least 3 million years, and fossil fuel emissions have become the dominant driver of the changes to our climate. In a world potentially several degrees warmer than the one that spawned our civilization, we had better ready ourselves for some surprises.

This isn’t alarmism; it’s just sensible risk management. Retired US Navy Rear Admiral David Titley, now head of Penn State’s Center for Solutions to Weather and Climate Risk, pointed out that governments still spend money on defence, despite the declining number of people killed worldwide in war. He told the US Congress that “we rightly invest in our security and defence as one component of hedging against unknown or unlikely security risks”. Inaction on climate change violates that same fundamental risk-management principle.

What’s nature ever done for us?

Of course, nature will carry on regardless, albeit savaged. As the MIT physicist and humanities professor Alan Lightman has noted, “tornadoes, hurricanes, floods, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions happen without the slightest consideration for human inhabitants”.

Yet if we turn our backs on nature, while at the same time climbing the population hill to nine billion, we will create a horrid future for humanity’s survivors, with ongoing wild species extinctions and a world polluted by human-invented chemicals.

Some have predicted that, within just two or three centuries, we could be alone except for pets, chickens, livestock, and an unknown suite of microbes and freeloaders such as mice and cockroaches.

For a sneak preview of this “biosimplification”, look no further than the swathes of European countryside where there has been a crash in bird populations – no songs, no glimpses of plumage, just an eerie silence – as a result of the wholesale ripping up of hedgerows, draining of wetlands and ploughing over of meadows robbing farmland birds of their homes and sustenance in order to boost farming production.

That would leave us living in a drab, crummy landscape where surviving native plants cower in small niches away from the weeds; zoos exhibit a lost fauna; and biophilia is reduced to watching carp.

It’s surely a trajectory that’s worth getting off.