Q: How do you confuse an Irishman? A: Put him in front of two shovels and ask him to take his pick Q: How do you get an Irishman on the roof? A: Tell him drinks are on the house. Q: Why did the Irishman fall out the window? A: He was trying to iron his curtains.

Ah yes, the Irish joke, beloved of northern English comedians in the 1970s, but driven underground by killjoys and lefties in the 80s and 90s, along with jokes about Blacks, “Pakis” and Jews. Or so we thought.

It would appear that jokes about stupid and drunken Irishmen live on in Australia and not just in underground clubs in Hicksville, but at the highest political level.

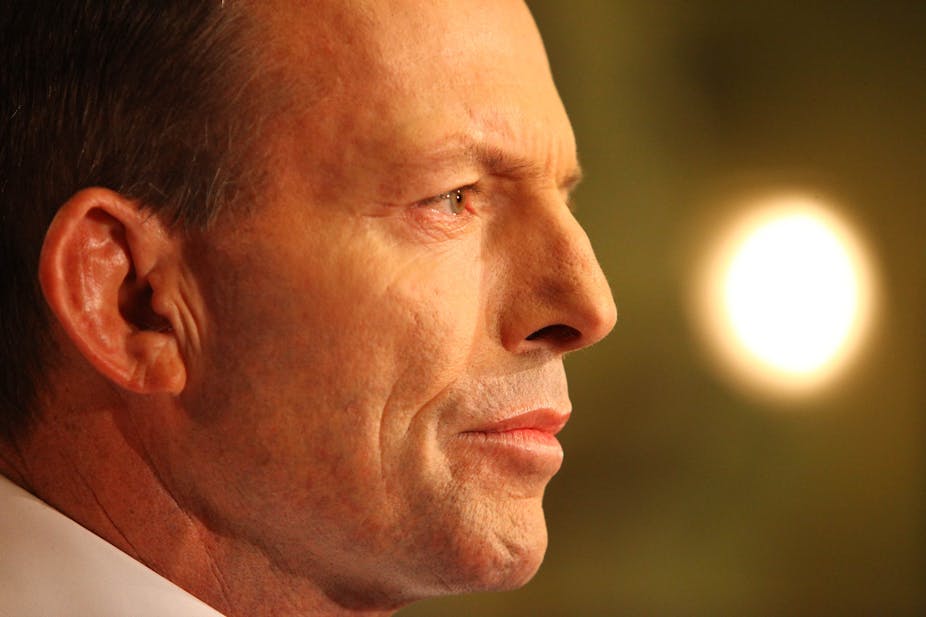

In a recent speech to his Liberal Party colleagues the leader of the opposition Tony Abbott brought the house down with the quip, “This government’s a bit like the Irishman who lost ten pounds betting on the Grand National and then lost 20 pounds on the action replay.”

Funny and harmless? Or toxic and offensive? Or maybe just ill-judged and antediluvian? It certainly seems out of place and anomalous.

It would be hard to imagine a senior politician in America or UK playing around with ethnic jokes. The equivalent might be Sarah Palin comparing the Democrats to stupid Polacks - pretty unimaginable now, even for her. Nor would a senior Irish politician quip about “Kerrymen”. (Kerry was the county in Ireland, which when I was child in Dublin, was the butt of our jokes.)

I remember being struck shortly after I moved to Sydney last year (from London) when I encountered golliwogs for sale at the airport. This would be a pretty rare sight these days in the UK. But you would expect Britain to have a more sensitive attitude to the depiction of Afro-Caribbeans, just as Australia will be more alert to stereotypes and slurs on people from the Far East.

However you might feel about “political correctness gone mad”, who can regret that the political culture in Birmingham would no longer allow the British Conservative party to run its 1964 anti-immigrant election slogan - “Want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Liberal or Labour”?

Much derided ‘PC" has succeeded in making us more mannerly and polite to each other, old-fashioned virtues, of which one would expect conservative politicians to approve.

Nonetheless, one needs to be careful about being too puritanical about comedy. It does not lend itself to hard and fast principles, not least because it relishes transgression, puncturing social taboos and hypocrisies.

The thrill of misbehaving that we relished as children finds its adult equivalent in saying forbidden things. The laugh often comes from the “I can’t believe he just said that” feeling.

One can forgive a lot if a joke is funny, but what makes it funny is deeply context-dependent – who is telling the joke and who is listening. Jewish jokes delivered by Woody Allen or Larry David might not work coming from someone else. Would Abbott have told an anti-Jew joke in a speech? His Irish joke seemed blithe rather than daring, anachronistic rather than transgressive - an English import that has disappeared from England.

The Irish joke, and its antecendet the Irish bull has a long history. In “An Essay on Irish Bulls” (1802), the Anglo-Irish writer Maria Edgeworth wrote of a laughter of thick-skinned superiority: “the ignorant, happily unconscious that they know nothing, can be checked in their merriment by no consideration, human or divine. Theirs is the sly sneer, the dry joke, and the horse laugh.”