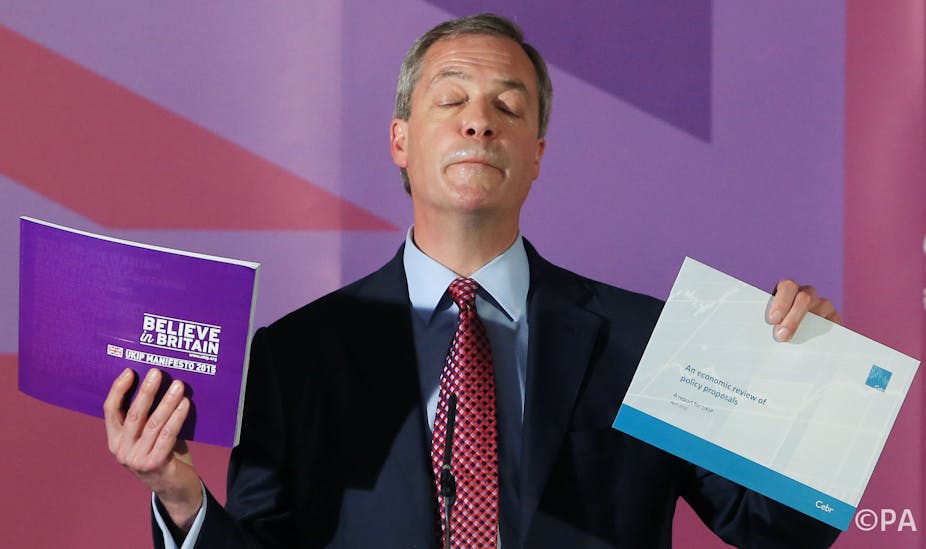

To the surprise of no-one, UKIP’s leader identified the European Union as his party’s top priority at the launch of its 2015 election manifesto.

The two-page Brexit plan, which is laid out across a backdrop of a very brash British flag, offers some interesting insight into UKIP’s vision of the UK-EU relationship. It is a “roadmap to freedom: the process that will lead Great Britain out of the EU and into the world”.

This sets out the stages of how a Brexit would supposedly work. But even though this has been billed as a fully-costed manifesto, the Brexit plan neglects to take account of a significant cost. If the UK leaves Europe but continues to participate in some projects – as UKIP suggests – it will have to pay for the privilege, just like other countries do.

Unlike the Conservative Party, which has pledged to hold a European referendum by 2017, UKIP wants an in/out vote to be held as soon as possible. The manifesto even suggests a question for the vote: “Do you wish Britain to be a free, independent, sovereign democracy?”

This question is obviously misleading. It doesn’t even mention the word “membership”, let alone “Europe”. It is clearly meant to attract anti-EU voters who already believe the EU is undemocratic and threatens national sovereignty. If a referendum were held, the question would have to be far more neutral than this suggestion.

But even more misleading is the portrayal of the status quo. The manifesto states that UK ministers and European politicians alike have “confirmed there is no hope of Britain negotiating any opt-outs, or special treatment” from within the EU. But it already has, with exemptions negotiated for the UK on the economic and monetary union, the Schengen area, and some policies on security and justice.

Despite this, UKIP still presents the EU as an undemocratic and inflexible institution that threatens the UK’s influence in the world.

Fully costed?

Should British citizens vote in favour of Britain being “a free, independent, sovereign democracy”, UKIP would set a fixed date, two years ahead, for leaving the European Union.

Negotiations with the EU would then start in order to negotiate a new form of partnership. The main objective of these negotiations would be to seek continued access on free-trade terms to the EU’s single market.

It would also continue to participate in a wide range of EU policies, including extradition treaties, cross-border intelligence, disaster relief, accommodation of refugees, pan-EU healthcare arrangements and various other cultural projects.

The main weakness of this plan is that access to the single market and continued participation in all these agreements necessarily has a cost, which is largely ignored.

The possibility of an associated form of membership, whether through the European Economic Area or special arrangements following the Swiss example, could also come to the table, but these too would have a cost for the domestic budget.

Norway, for example pays around €1.63bn a year for its EEA membership. It also paid an additional €296 million in 2013 to participate in EU programmes and agencies.

On top of these financial contributions, the political costs should not be ignored: both Switzerland and Norway have to implement most of the EU’s single market legislation and, in most cases, are excluded from the decision-making process.

Either option would also offer the UK less protection, not more, from the EU decisions that would inevitably still affect it – such as market regulation, tariff barriers (through Customs Union membership) and social policies falling within the scope of the Single Market.

All in all, UKIP’s Brexit proposal is remarkably muddled, and does not offer much of a plan for the UK to leave the European Union. The party wants a referendum as soon as possible and hopes the UK will vote to leave the EU, but also essentially wants to remain part of the EU in a variety of ways. It wants to have its cake and eat it, which is a policy that won’t hold up to much scrutiny.