People under 30 don’t need to care about – or even understand – this. But there really was a time when exposure to culture was mediated by curators who had far too much power over what we all saw, heard or experienced.

In the era before social media and widespread internet access, artists had no direct connection to their fanbases, and required whole distinct manifestations of media to communicate news of their activities, directions and products.

We had a film press, a television press, a literary press – and a music press.

Review: Full Coverage – Samuel J. Fell (Monash University Press)

I needed to read Samuel J. Fell’s Full Coverage, the first (and surely only) ever history of Australia’s rock press, for selfish reasons: I consider my tastes and values to have been significantly shaped by the phenomenon.

Over 300 pages, Fell surveys the development of local rock music coverage in (mainly national) magazines, stopping to inspect some of the eccentric and/or dedicated writers, editors and publishers who made the greatest impact along the way.

My first music writing was published in Vox, the short-lived tabloid “muzpaper”, in 1980 – and I flitted at the edges for more than a decade afterwards.

In a “journalism” career I was lucky enough to bail from a few years before the internet began to bite, I was more involved in teenage (largely, pop-oriented) colour magazines than in the out-and-out rock press in Australia. Nonetheless, I would read rock publications voraciously and I never passed up the opportunity to contribute.

There are a lot of people named in this book I have met, befriended or worked for, in my ten or more years working in publishing in Sydney in the 1980s. In that regard, Fell’s narrative has a strange, dreamlike quality for me.

Reading Full Coverage, I learned some interesting background and connections between particular writers, editors and publishers – I gained a new historical understanding of the field. There were also things that Fell failed (or perhaps chose not) to include.

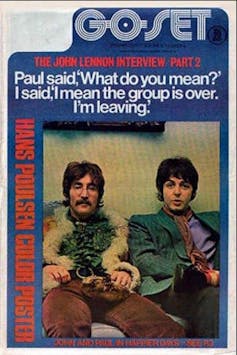

Molly, Lily and Go-Set

After some courageous short-lived forays, the Australian music press started in earnest in 1966 with the Melbourne-based Go-Set. Set up by university students, whose only prior experience was Monash University’s paper, Go-Set quickly filled a need for information and connection among pop fans.

Enthusiastic writers like Lily Brett, Ian (Molly) Meldrum, Johnny Young and Douglas Panther conveyed the inside story of the lives of musicians and celebrities, while maintaining a particular accessibility for their “teens and twenties” readers.

Meldrum’s famous tale of being told by John Lennon that the Beatles were breaking up (Meldrum didn’t quite take it in, and it wasn’t until someone at Go-Set listened to the interview tape he sent back from London that the story “broke”) isn’t in this book.

But Brett’s testimony of the global pop stars – Janis Joplin, the Mamas and the Papas, Jimi Hendrix – she talked to one-to-one gives us a sense of the importance the magazine held for its readership.

Go-Set’s publisher, Philip Frazer, went on, in a haphazard way, to bring a Rolling Stone franchise to Australia.

“Stone”, as Fell and his informants insist on calling it, has been running locally ever since. In its early days, it coexisted with some key 1970s and 1980s tabloids, namely Juke and Rock Australia Magazine, popularly known as RAM.

In the early 1990s, a substantial part of the Rolling Stone staff, including Toby Creswell and Lesa-Belle Furhagen, broke with its publisher Philip Keir and set up their own magazine, Juice. Accounts vary among players about what led to the split.

Oddly, Fell muses on Juice’s similarity to the American Spin for many pages, before he notes that a proportion of its editorial was directly licensed from that publication. This was the case to the degree that the Spin logo was on the cover of early issues!

Read more: Molly is lacking as a TV show but millions, including me, are hooked

Street papers: ‘uniquely Australian’

The next format to crash down all assumptions about best music journalism models were the “street papers”, which Fell suggests were a uniquely Australian creation. Their extensive advertising revenue from venues, record companies and related industries allowed these publications to be provided at no cost.

The street paper killed RAM and Juke, not by being anywhere near as good, but far, far cheaper. The finale of Full Coverage is the whimper-not-a-bang decline of music-based print media in the face of social media, mercifully hastened by the pillow-on-the-face of Covid.

Fell loves the “street papers”, and one gets the sense he would happily have written about them alone. He does concede a lot less time went into them editorially, compared to those that cost money – like Juke or RAM (or Vox!).

But he doesn’t spend a lot of time on the obvious additional truth that the street papers’ editorial positions tended to be driven by the advertising dollar, which meant negativity was almost always absent from reviews. Indeed, advertising was really the only way to guarantee a feature or review.

I am reminded of a time when the editor of a street paper I occasionally wrote for declared a special issue, in which all writers would be permitted to opine freely on anything they wanted. The plan was later abandoned.

Fell explains a lot in this broad history, though he too often takes his informants at their word, and uses their words as his basis, I suspect, to construct his narrative.

He probably had no choice, given the unavailability of archives. Most of the publishers I worked for had no respect at all for legislation requiring copies of all published material to be presented to the relevant state library and the NLA.

Undeniable soap operas

He was surely dissuaded, probably by word-count considerations – but perhaps also by lawyers – from getting his hands dirty in the ins-and-outs of the personalities and behaviours of the individuals he’s writing about. What’s the word for respecting an author’s restraint, while wishing there was just a bit more goss within their pages?

Of course, there were many links between the producers of music magazines and the people they wrote about. By links, I don’t just mean romantic or domestic entanglements, though I do mean that, of course. There are also great, undeniable soap operas.

A public spat between Steve Kilbey of The Church and music journalist Stuart Coupe in the early 1980s springs to mind.

It would appear that Kilbey and Coupe spent a long time talking for a feature, during which Kilbey made some broad claims about his own genius. Coupe recorded the conversation and published some choice elements in RAM – to some derision from readers. (Though let’s be clear: Kilbey at his best is pretty good!) But no doubt there were hundreds more conflicts – some manufactured, others heartfelt – between artist and reporter/critic.

Similarly, Fell either doesn’t know or doesn’t care about the connection between the music press and TV, which was strong. Channel 0/10 shows, such as Uptight in the late 1960s, featured content and tie-ins with the “teens and twenties” magazine Go-Set.

Michael Gudinski’s failed foray with the early 1970s paper (Daily) Planet was repeated with a TV show, WROK, a decade later – in both cases, Gudinski failed to understand the difference between advertising and journalism. Nor does Fell mention the tragically hilarious “burial” of Go-Set following its demise, broadcast on the ABC kids’ show Flashez in the mid-1970s.

Then there are careers like that of radio announcer, pop singer and jockey Donnie Sutherland. Fell remarks on Sutherland’s induction into the world of Go-Set, but doesn’t mention his subsequent 12-year career as host of Sounds on Channel 7 – which is how most readers would remember him.

Fell also touches on Countdown magazine briefly, as a tie-in between Australia’s best known and (still) best loved TV pop show. But he hardly mentions the magazine’s content: Countdown used its biggest advantage – that the show was incredibly popular and any magazine called Countdown was going to sell – to go outside musical coverage and engage with its readers’ lives, opinions and politics.

More generally, it needs to be noted that, of course, context can get out of control. Personally, though, I could have handled the sacrifice of some of the half-remembered accounts of ins and outs of owners and editors, in return for more discussion of the publications’ content and impact.

No doubt Fell has a life, and lives can easily be frittered away reading old music magazines. But discussion, for instance, of Jen Jewel Brown’s piece for the early 1970s Daily Planet on the tribulations of being a woman writing about music would have revealed plenty.

Read more: Friday essay: punk's legacy, 40 years on

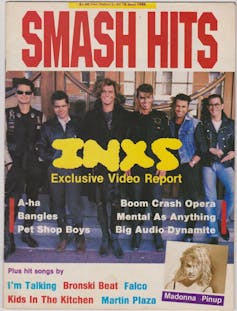

Smash Hits and Rolling Stone

Back to the topic of Countdown: Fell pays its competitor, Australian Smash Hits, minimal notice. I worked for this magazine (primarily as features editor) between 1984 and 1991. While most definitely a music magazine, it really isn’t in Fell’s terrain. Its readers ranged from the very young to the mid-teens – they were more into “pop” than “rock”.

But I do believe to suggest Smash Hits was “struggling” in the mid-to-late 1980s, as Fell does, is a misrepresentation: it had its ups and downs, but it was the national market leader in music magazines for at least ten years after its launch in 1984, outselling all others. In short, it was the leading music magazine of its era, and someone is feeding Fell misinformation.

That it sold the most is not an argument for the magazine’s quality, of course, though it had its moments. I mention this because it speaks once again to the problem with dependence on oral history: given the long-ago demise or sell-off of various publishers, historical sales figures are largely unattainable and subject to the vagaries of memory. Fell didn’t talk to anyone from (or even really about) Australian Smash Hits.

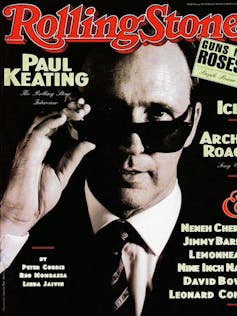

Which only leaves the elephant in the room.

Rolling Stone has, of course, a 50-year history in Australia. Whereas Australian Smash Hits was often criticised for including content from its British parent, the first decade of Rolling Stone in this country was typically little more than a distillation of old cut-and-pastes from the American magazine. (Fell alludes to this, but doesn’t mind.)

Rolling Stone was often a shambles, and Fell appropriately gives the most space to its best era, under Kathy Bail’s editorship, when a few great moments – the Paul Keating cover most of all – brought it dangerously close to relevance.

Fell discusses the defection of key players, which led to Bail’s recruitment by publisher Philip Keir. And he gives credit to Keir and Bail for recognising the importance the internet was going to play in media, moving towards the 21st century.

‘I thought it was sci-fi nonsense’

No one could have imagined the changes afoot, of course, but I take my hat off to Keir for seeing it more clearly than most of us. I spent time with him for a few weeks in the mid-1990s while he employed me to work up another publication for his stable – and he availed me of his knowledge of, and passion for, the possibilities of online publishing.

I was impressed that he believed it, but I thought it was sci-fi nonsense. In less than ten years, as you know, the whole landscape of print media was lacerated.

Of course, there is still a music press: look at the preposterously overblown global influence of Pitchfork, for instance. In Australia, the music press only takes print form in the most boutique of varieties, like Melbourne magazine Efficient Space. A whole social realm, a way of understanding a culture, is gone. Is that bad?

Ironically, online resources can help us understand whether it is or not – for instance, the University of Wollongong’s repository of the best 1970s-80s rock magazine of them all, Adelaide’s Roadrunner.

If Fell’s book doesn’t entirely convey why Australian rock journalism was worth the candle, the six years of Donald Robertson’s witty, passionate, innovative paper just might.