Scotland’s independence referendum last September captured the international imagination. Ultimately, Scotland’s electorate voted 55% to 45% to stay in the United Kingdom, but this is clearly not the end of the story.

Mainstream politics have been shaken up, especially in Scotland, and the political elite now has to confront a bigger issue: the ongoing evolution of its political landscape and the lingering confusion over the UK’s constitutional make-up.

Referendum’s legacies live on

One of the largest impacts and successes of the referendum was the mass mobilising of a political conversation at grassroots level. Certainly the guiding compass of the debate earned plaudits for being centred on a civic national question, not an ethnic one.

Arguably this debate, with the exception of its extremes, was not about nationalism at all. Rather, it was about a contemporary internationalism and a new settlement between nations (the UK is a collection of nations after all).

Certainly, there was to be no simple disappearing of “Britain” with independence. For example, the monarchy would have remained. Unless a separate referendum on a republic was held, the monarchy is British (that is, there is technically no Queen of England), made from a union of the Scottish and English crowns.

Importantly, much of the referendum debate centred on issues of social justice and social democracy outcomes, on protecting the National Health Service from privatisation and starting to unhitch from the neo-liberal economic agenda of mainstream Westminster. Oh, and Trident – there is a strong anti-nuclear weapons edge to the Scottish electorate’s concerns, as the UK nuclear arsenal is housed in deep water on the west coast of Scotland.

Social media massively aided this grassroots engagement with politics. The Yes camp was particularly active and successful in this regard, and did so across traditional party lines – to mobilise for a movement and not for a specific party (the SNP). In the end, 45% voting for independence probably surprised many people. It was a very close call.

The vote may well have been more like a 50-50 result had the Westminster leaders not all high-tailed it to Scotland in the final week of the referendum campaign. They campaigned hard to reinforce their relatively negative strategy of focusing on the economic risks of leaving the UK and some hasty promises on further devolution for Scotland.

‘Business as usual’ approach fails

Nevertheless, the referendum outcome has not led to a return to the status quo – at least, not as much as the mainstream Westminster UK parties had hoped for. In fact, the Westminster response and “business as usual” approach has been perceived as an obdurate dismissal of the Scottish electorate’s concerns.

For example, after promising in the wake of the referendum to deliver more on Scotland’s concerns for devolution, the Westminster and media debate quickly gravitated to discussion on a perceived democratic deficit and a stoking up of Scotland versus England rhetoric. This included debates over the democratic deficit for English voters, with the Conservatives and UK Independence Party (UKIP) playing on petty nationalist fears by proposing EVEL (English Votes for English Laws) at Westminster.

Therein lies the conceit because there is a default assumption that Westminster is a de facto English parliament, which it is not: it is a British parliament and responsible to represent all of the UK’s constituent interests. So confusion reigns, with strategies of playing on the fears and misapprehension of voters as a mode of realpolitik due to the small matter of the UK general election on May 7 (and the need to shore up English confidence in Westminster).

The front pages of the UK and Scottish editions of The Sun (a Murdoch instrument) – one endorsing the Conservatives, the other the SNP – neatly sum up the aspirations of both the paper and the Conservatives in terms of keeping Labour out of office.

Nevertheless, and to his credit, Labour leader Ed Miliband has pushed back against the stirring of petty nationalism in England, recognising that the Conservative strategy is to divide and rule.

SNP reshapes electoral calculus

The problem for Labour is that the party is on the verge of a wipe-out in Scotland, and Labour has always depended on a significant swathe of Scottish seats to form a government in Westminster. Indeed, Labour may well still depend on Scottish seats but with SNP MPs sitting in them.

The SNP is widely predicted to win around 55 of Scotland’s 59 seats come the morning of May 8. The party currently has only six seats and in UK terms has been relatively insignificant. Not any more.

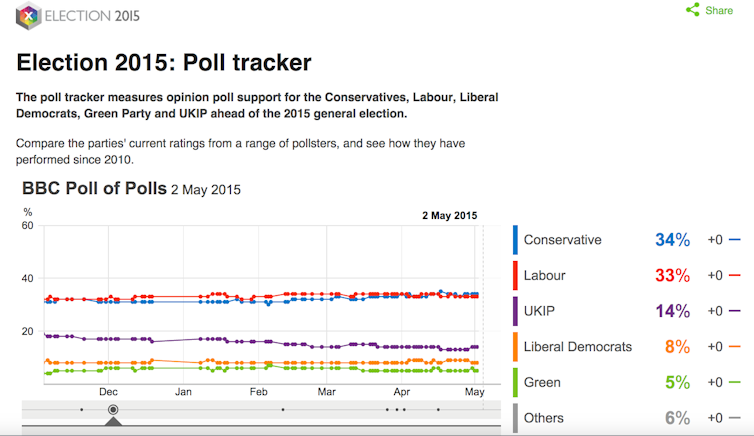

Yet mis-direction is freely available; not least due to the highly complex nature of UK constitutional arrangements and its election process. If you were to go by the BBC poll tracker below, then you’d really have no sense that the SNP is not only a credible political force but on the verge of being the third-largest political party in the UK, where it may well remain for a generation.

Going by this poll, UKIP appears in a strong position but can only really expect to win a few seats. The SNP is not even on the chart (but mixed in with “Others”) and yet can feasibly win between 54 and 59 seats. The SNP membership has surged and is the third-largest party membership in the UK – well over 100,000 and only just short of the Conservative’s membership numbers – so the party is also becoming wealthy.

Establishment politics under challenge

It is the current system that has both caused confusion and enabled this political shift, and the establishment is doing its best to shout it all down as if it’s some sort of undemocratic revolution. Of course, they don’t want the challenge to appear to be a legitimate threat to their own party-political rhetoric on democracy.

It is clear that a shift is happening. One of the most edifying outcomes of election is the prominence of woman politicians in the shape of the leaders of the Greens (Natalie Bennett), Plaid Cymru (Leanne Wood) and the SNP (Nicola Sturgeon). All have performed with and inspired confidence.

Sturgeon has performed particularly well to a UK audience, with voters in England even wondering if they could vote for her or the SNP. In fact, she is not even standing for Westminster election and the SNP (as you might expect) is not contesting any seats outside Scotland.

What is certain is that after May 7 it is out of the electorate’s hands. Come May 27, a party or coalition must win the confidence of the House of Commons to deliver the Queen’s speech to form a government.

Confusion reigns? To quote Francis Urquhart from the original House of Cards: you might very well think that, but of course, I couldn’t possibly comment.

You can read more of The Conversation’s comprehensive UK election coverage here.