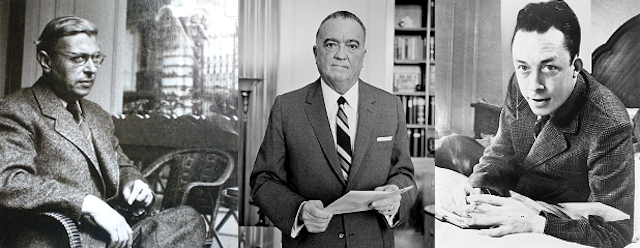

On 7 February 1946 we find J Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI, writing a letter to “Special Agent in Charge” at the New York field office, to draw his attention to one ALBERT CANUS, who is “reportedly the New York correspondent of ‘Combat’.”

Hoover complains, “This individual has been filing inaccurate reports which are unfavorable to the public interest of this country”. He gives orders for the New York field division to “conduct a preliminary investigation to ascertain his background, activities and affiliations in this country.”

One of Hoover’s agents finally has the guts to correct the chief and tell him that “the subject’s true name is ALBERT CAMUS, not ALBERT CANUS”, but diplomatically hypothesised that “Canus” was an alias he had cunningly adopted.

The year before, the New York team had already sprung into action to keep an eye on the activities of visiting French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre. It was a time when everyone was potentially a Communist, but especially ex-resistance French philosophers. So it was the Untouchables in pursuit of the unintelligible.

The surprising outcome revealed by the FBI’s own files is that the G-men subtly morph into E-men, not just keeping philosophers under surveillance but pursuing their own philosophical investigations.

Nausea in New York

Sartre and his fellow journalists were actually invited by the Office of War Information, with a view to disseminating positive propaganda messages about the American war effort in 1945. Sartre’s main champion was under-secretary of state, Archibald Macleish, now best-known as the author of the classic formulation of the modernist aesthetic: “A poem should not mean/But be”. The author of Nausea and Being and Nothingness duly delivered a classically existentialist article about how he was suffering from “le mal de New York” – New York sickness or Nausea in New York.

Sartre was interpreted as a slippery customer capable of evading surveillance. One agent, who is supposed to be keeping a tail on him, followed him to Shenectady, where Sartre was supposed to be singing the praises of the General Electric plant. But he ducked out and hopped on a train “on the afternoon of March 1, apparently bound for New York City”. In other words, the hapless agent – Special Agent Richard L Levy –- lost him. We don’t know if perhaps he just wasn’t all that keen on Schenectady, and preferred the pleasures of the big city, where he had a girlfriend, which Special Agent Levy also did not know about.

Outsider in the Big Apple

On March 25 1946, Albert Camus disembarked the SS Oregon at Pier 86, New York, where he was duly stopped and searched in line with Hoover’s stop notice. Despite which he proceeded to fall in love with New York and in New York, finding a girlfriend from Vogue magazine, Patricia Blake, who, noticing his extreme interest in death, bought him copies of Casket and Sunnyside, the undertakers’ monthlies.

Camus was being hosted by Justin O’Brien, professor of French literature at Columbia University. Like Archibald Mackenzie, O’Brien was also a member of the proto-CIA, the Office of Strategic Services. A celebrated translator of the journals of André Gide, he was also chief of the French desk at the OSS, concerned with “establishing intelligence networks behind German lines in France”.

The precursors of the CIA, Mackenzie and O’Brien, clearly had an aesthetic or philosophical sensibility. The FBI agents, having stolen papers from the French philosophers, were incapable of reading the original (“[it’s] all in French”, they complain) and had to draft in translators. But there is a curious rapprochement between wandering Existentialists and the agents. Communism doesn’t really make sense to the FBI. Why? Because nothing does.

I am indebted for this thought mainly to agent James E Tierney, of the New York field office, who in response to continued pestering from Hoover – what the hell is Existentialism anyway? – came up with several pages. He is the very archetype of the philosophical detective: a G-man poring over the pages of The Myth of Sisyphus. Here he is on Camus: “This philosophy recommends living with the absurd, enjoying life all the more fully because it has no meaning.”

Philosophically speaking, the FBI agents stake a claim as neo-Existentialists in the classic early Sartrian mould, or crypto-Absurdists. They, like the early Archibald Mackenzie, take the view that people, not just poetry, should not mean, but be. They certainly subscribe to the “hell is other people” school of thought. And they are anti-narrativists or, as agent Tierney would say, “painfully lucid in the face of life’s irrationality”.

The FBI echos Sartre’s classic modernist critique of narrative in Nausea. Narrative is teleological – it has a purpose – whereas life is anti-telos. The CIA believe in narratives, whereas Hoover’s FBI are quintessential Existentialists in refuting narrative. They would rather have contingency and chaos than telos. The FBI find Camus fundamentally their kind of guy: the Camus of the Absurd and the Outsider, according to which the individual will never really make sense of the world, nor hook up, in any kind of meaningful, long-term way, with others.

Losing the plot

We are apt to think of the FBI as the great conspiracy theorists, but the reality is more nuanced: they don’t really want to believe in plots. Was the assassination of JFK a conspiracy? The FBI won’t have it. Later on in their files, we find them, in their typically Existentialist way, intent on the Oswald lone-wolf story – or non-story. Naturally, when it comes to 9/11, it is understandable that the FBI really were not conspiratorial enough in their thinking. It’s not that they have lost the plot, they just don’t want to know about plots. They are plot-sceptics.

Narrative, philosophy, and espionage share a common genesis: they arise out of a lack of information. What happened, for example, to the elusive Albert Canus, the original cause of Hoover’s anxiety attack? One agent, James M Underhill, desperate to find someone actually called “Canus”, finally tracked him down on 18 March 1946. Canus, the agent reports, was in fact apprehended by Border Patrol in New Orleans, living at 1622 Jackson Avenue.

He “claimed” to be a “messboy” on the SS Mount Everest, which docked in New Orleans in 24 April 1943. The ship sailed away again on 3 May and he didn’t. Immigration officers were planning to put him on another ship but, says Underhill, existentially unconcerned with the telos: “the file does not show the final disposition”.

This is an edited version of an essay first published in Prospect Magazine based on a lecture given earlier this year at the Maison française, Columbia University, New York, as part of its centenary celebrations.