The Y chromosome is a never-ending source of fascination (particularly to men) because it bears genes that determine maleness and make sperm. It’s also small and seriously weird; it carries few genes and is full of junk DNA that makes it horrendous to sequence.

However, new “long-read” sequencing techniques have finally provided a reliable sequence from one end of the Y to the other. The paper describing this Herculean effort has been published in Nature.

The findings provide a solid base to explore how genes for sex and sperm work, how the Y chromosome evolved, and whether – as predicted – it will disappear in a few million years.

Making baby boys

We have known for about 60 years that specialised chromosomes determine birth sex in humans and other mammals. Females have a pair of X chromosomes, whereas males have a single X and a much smaller Y chromosome.

The Y chromosome is male-determining because it bears a gene called SRY, which directs the development of a ridge of cells into a testis in the embryo. The embryonic testes make male hormones, and these hormones direct the development of male features in a baby boy.

Without a Y chromosome and a SRY gene, the same ridge of cells develops into an ovary in XX embryos. Female hormones then direct the development of female features in the baby girl.

A DNA junkyard

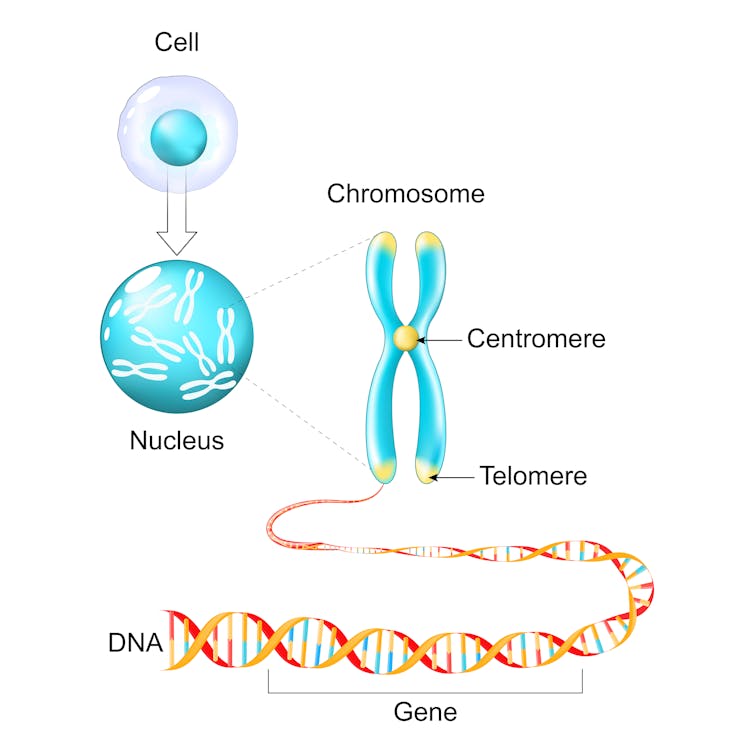

The Y chromosome is very different from X and the 22 other chromosomes of the human genome. It is smaller and bears few genes (only 27 compared to about 1,000 on the X).

These include SRY, a few genes required to make sperm, and several genes that seem to be critical for life – many of which have partners on the X. Many Y genes (including the sperm genes RBMY and DAZ) are present in multiple copies. Some occur in weird loops in which the sequence is inverted and genetic accidents that duplicate or delete genes are common.

The Y also has a lot of DNA sequences that don’t seem to contribute to traits. This “junk DNA” is comprised of highly repetitive sequences that derive from bits and pieces of old viruses, dead genes and very simple runs of a few bases repeated over and over.

This last DNA class occupies big chunks of the Y that literally glow in the dark; you can see it down the microscope because it preferentially binds fluorescent dyes.

Read more: We discovered a missing gene fragment that's shedding new light on how males develop

Why the Y is weird

Why is the Y like this? Blame evolution.

We have a lot of evidence that 150 million years ago the X and Y were just a pair of ordinary chromosomes (they still are in birds and platypuses). There were two copies – one from each parent – as there are for all chromosomes.

Then SRY evolved (from an ancient gene with another function) on one of these two chromosomes, defining a new proto-Y. This proto-Y was forever confined to a testis, by definition, and subject to a barrage of mutations as a result of a lot of cell division and little repair.

The proto-Y degenerated fast, losing about 10 active genes per million years, reducing the number from its original 1,000 to just 27. A small “pseudoautosomal” region at one end retains its original form and is identical to its erstwhile partner, the X.

There has been great debate about whether this degradation continues, because at this rate the whole human Y would disappear in a few million years (as it already has in some rodents).

Sequencing Y was a nightmare

The first draft of the human genome was completed in 1999. Since then, scientists have managed to sequence all the ordinary chromosomes, including the X, with just a few gaps.

They’ve done this using short-read sequencing, which involves chopping the DNA into little bits of a hundred or so bases and reassembling them like a jigsaw.

But it’s only recently that new technology has allowed sequencing of bases along individual long DNA molecules, producing long-reads of thousands of bases. These longer reads are easier to distinguish and can therefore be assembled more easily, handling the confusing repetitions and loops of the Y chromosome.

The Y is the last human chromosome to have been sequenced end-to-end, or T2T (telomere-to-telomere). Even with long-read technology, assembling the DNA bits was often ambiguous, and researchers had to make several attempts at difficult regions – particularly the highly repetitive region.

So what’s new on the Y?

Spoiler alert – the Y turns out to be just as weird as we expected from decades of gene mapping and the previous sequencing.

A few new genes have been discovered, but these are extra copies of genes that were already known to exist in multiple copies. The border of the pseudoautosomal region (which is shared with the X) has been pushed a bit further toward the tip of the Y chromosome.

We now know the structure of the centromere (a region of the chromosome that pulls copies apart when the cell divides), and have a complete readout of the complex mixture of repetitive sequences in the fluorescent end of the Y.

But perhaps the most important outcome is how useful the findings will be for scientists all over the world.

Some groups will now examine the details of Y genes. They will look for sequences that might control how SRY and the sperm genes are expressed, and to see whether genes that have X partners have retained the same functions or evolved new ones.

Others will closely examine the repeated sequences to determine where and how they originated, and why they were amplified. Many groups will also analyse the Y chromosomes of men from different corners of the world to detect signs of degeneration, or recent evolution of function.

It’s a new era for the poor old Y.