Uncommon Courses is an occasional series from The Conversation U.S. highlighting unconventional approaches to teaching.

Title of course:

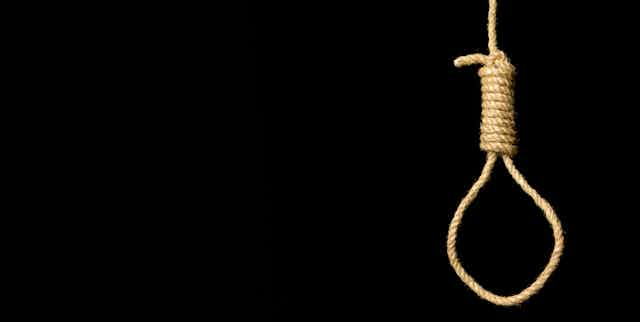

Lynching and the Press

What prompted the idea for the course?

One of my students was reviewing a spreadsheet that listed total lynchings by state. She exhaled, and then, with a bit of weariness, said, “Mississippi, goddamn.”

She was trying to comprehend the enormity of violence against the Black population of Mississippi: 823 lynchings from 1865 to 2011, according to the Tolnay-Beck and Seguin lynching inventories, two of the main academic resources in this field. She is one of 13 University of Maryland journalism students digging through historic newspaper articles and data tables this semester to learn about how U.S. newspapers covered lynching.

The class is an extension of an award-winning 2021 student journalism project called “Printing Hate,” published by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland, which examined various case studies of lynching coverage.

My class is taking a much longer view of this kind of journalism, using big data tools to examine newspaper coverage of lynchings from 1789 through 1963. In the process, students will gain important insights about our country’s history. They are learning about the societal context that allowed more than 5,000 mob-driven murders of Black citizens to happen and how some mainstream news coverage reinforced the violent white supremacy of these events. Newspapers, for example, frequently used dehumanizing language to describe the lynching victims as “fiends” or “black brutes.”

What does the course explore?

The core of the class involves analyzing data from 60,000 news pages captured from the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America database of historic newspapers. This project began as an academic study with my colleague Sean Mussenden, the data editor at the Howard Center and senior lecturer at the Philip Merrill College of Journalism. A prominent journalism historian, Kathy Roberts Forde, at the University of Massachusetts Amherst later joined our team.

After working with this large dataset, I decided to offer a class so students could learn research skills, such as data and content analysis, while also learning more about history and the history of U.S. journalism.

What materials does the course feature?

• “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases,” by journalist Ida B. Wells.

• “Journalism and Jim Crow: White Supremacy and the Black Struggle for a New America,” by Kathy Roberts Forde and Sid Bedingfield.

• “They Left Great Marks On Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I,” by Kidada Williams.

What’s a critical lesson from the course?

Working with a sample of this data from newspaper lynching articles, students compared the lynching location with the location of the newspaper. It took about three weeks for the class to classify some 3,000 news articles on a Google form and sheet that I had prepared. Students’ preliminary research is exploring why some Southern newspapers would cover lynching outside the state but not in their own backyards. Students are wondering if this was a form of erasure of local history.

Later this semester, my students will research the tone of newspaper narratives about lynching, such as how the news coverage portrayed the mob. The one graduate student in the class, who is pursuing her Ph.D. in history, is examining lynching in the antebellum era, a period for which there is very little research on this topic available.

Why is this course relevant now?

My students write weekly reflections about the readings and coursework. This course has opened their eyes to how the news media’s negative portrayals of African Americans can support systems of white supremacy. Few mainstream newspaper articles reflected Black voices, except, of course, the Black press.

What will the course prepare students to do?

These students will leave this class with in-depth data and content analysis skills. They will acquire a keen sensitivity to portrayals of Black Americans and other people of color in news coverage. Ultimately, we hope the course will lead to better journalism.