It is 20 years since the AIDS-related death of Derek Jarman, filmmaker, painter, author, gardener – and a crucial voice in gay politics in Britain. And when you look at his work today, two decades can seem like a very long time ago indeed.

The topics Jarman explored in his films and journals, and which drove his activism, remain very much with us – Britain’s imperial legacy, or AIDS and queer sexuality in relation to what he called the “hetero soc”, his idea of the normalising force of the heterosexually led society. But the contexts for these issues have changed enormously. Since the 1990s, the medical response to HIV has shifted completely and we now live in a world in which gay marriage is sanctioned by the state.

Meanwhile, the central London that Jarman was based in for most of his working life has been fully transformed by the gentrifying forces of property redevelopment. Art has become more of a global commodity than ever. Where some find socially liberal “progress” in these changes, I expect Jarman would have found material for savage social critique. He would have seen in this the forces of normativity, the pressures of neo-liberalism, masking the persistence of forms of intolerance of all kinds.

Marking this anniversary year, a number of individuals and institutions across London and beyond have joined forces in creating Jarman 2014, a loosely linked set of events, exhibitions and projects which explore Jarman’s work in various ways. My own contribution is an exhibition at the Cultural Institute at King’s College London, where I teach and where Jarman once studied. The exhibition explores his humanities education and his life in London.

Jarman was a student at King’s from 1960-63 before he went on to the Slade to study Fine Art. The common view is that he came to King’s to take a General Studies degree (a bit of history, english literature and art history) by way of bargaining with his middle-class RAF father, who wanted him to get a “real” degree before going off to art school.

This means that this period in his life is often overlooked. But studying the humanities was important to an artist like Jarman. It’s worth stating that unequivocally now, at a time when the humanities is under threat in various ways through funding cuts, ever more torturous metrics and general suspicions about relevance. More than many artists of his generation, Jarman engaged deeply with history, literature and art history.

Historical and literary snippets inform all of his work. We have the more blatant cases of his adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest and his homoerotic riff on the sonnets, The Angelic Conversation, as well as characters and places that are only hinted to, making reading or viewing his work an incredibly rich experience.

Jarman didn’t have a simplistic relationship to the history and the literature of the past. Sometimes readers and audiences detect nostalgia, a rose-tinted view of history, but this, I think, is to misunderstand him. While Jarman’s works are often informed by historical moments of a time before the industrialising, imperialising forces of modernity, he doesn’t look back longingly and uncritically. His view of the past may be something altogether queerer – less interested in continuity or even coherence, more interested in disrupting historical certainties and conventional thinking.

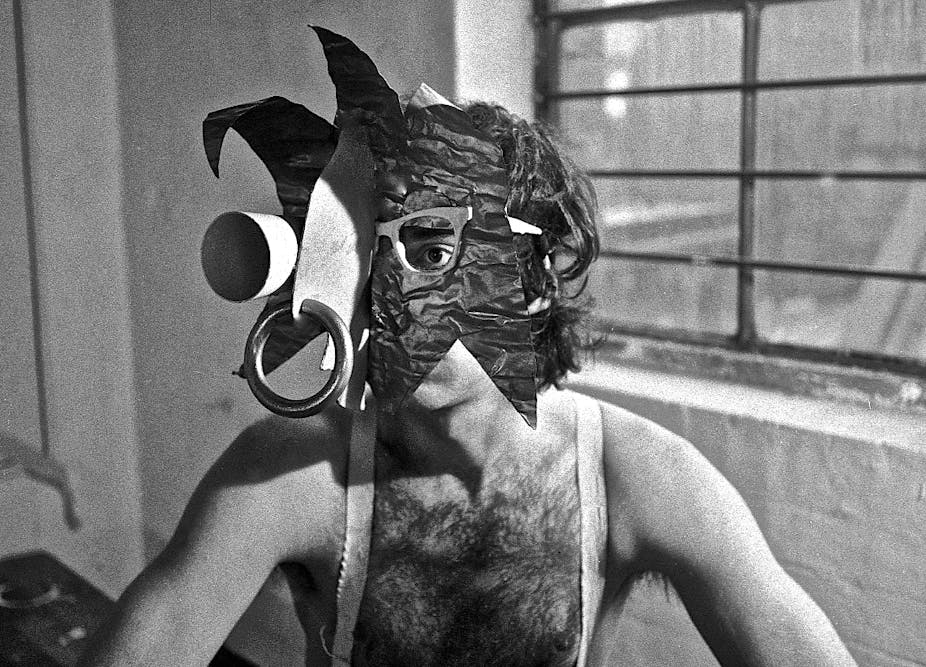

The figure of John Dee provides a good example of Jarman’s irreverent historicism. An alchemist, astrologer and magician known as “The Queen’s Conjuror” during the reign of Elizabeth I, Dr Dee was an important figure in Jarman’s work. He appears at the beginning of Jarman’s punk-aesthetic feature Jubilee, summoning angels and Shakespeare’s Ariel before the scene cuts to disaffected youth on the streets of contemporary London.

In this angry, ironic state-of-the-nation film about Britain, in the wake of the Queen’s jubilee celebrations in 1977, it is the magical figures of the past who disrupt and question our view of the present.

We look back at Jarman now as a particularly British kind of radical artist, a polymath across different forms and media. His radicalism can be seen not only in his development of a unique aesthetic and experimental practice, but also in the way he lived his life, as a queer artist-activist on the outside of movements, groups, and institutions.

What drives Jarman, which we see so clearly in his sketchbooks and notebooks, is curiosity and a continued hunger to learn, to read more and to rethink. In his continual pursuit of the past, re-imagined and re-fangled, we can see something of that important foundation as a student of the humanities. Jarman’s inquisitive and critical take on the world remains ever relevant, his transgressive vision continuing to inspire. And perhaps we should learn from his use of history, and see him as a figure who can still shake up our view of today.

Derek Jarman: Pandemonium is at London’s Somerset House until 9 March.